+ By Brenda Wintrode + Photos by Jay Fleming

It’s not our job to toughen our children up to face a cruel and heartless world. It’s our job to raise children who will make the world a little less cruel and heartless.

–L. R. Knost, Author and Social Justice Activist

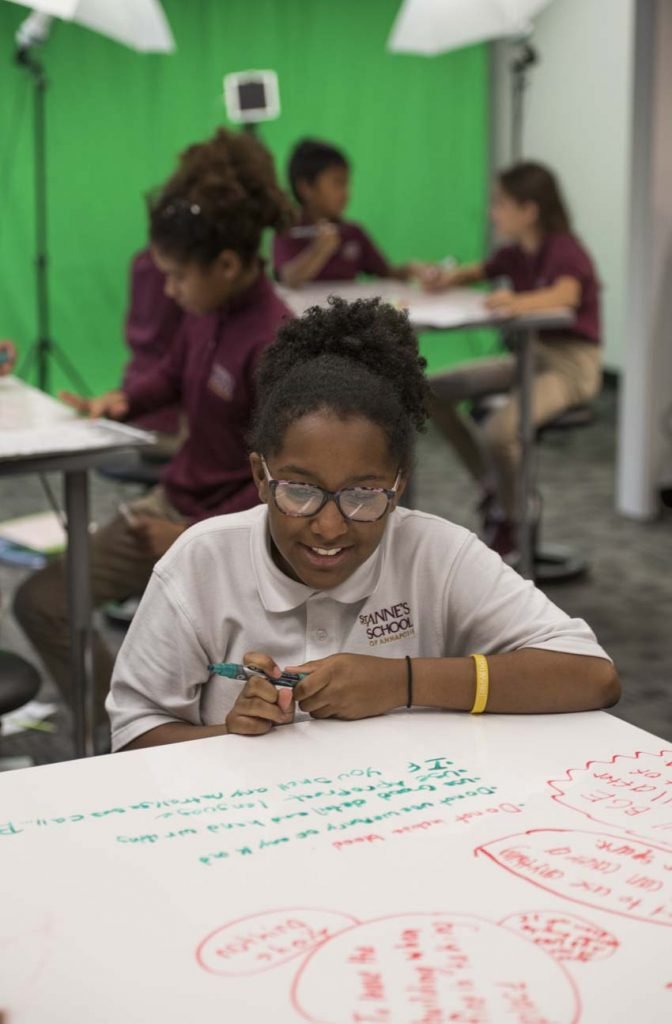

Eighth-grader Sage still remembers her first day at St. Anne’s School of Annapolis. “Everybody welcomed me in such a big way, and I made friends on the first day,” she says. The private day school was her fourth elementary school. She sits up straight at the head of the conference room table, where five of her schoolmates, all clad in burgundy and khaki school uniforms, give her their earnest attention. She tells us in a soft voice that she was shy “back then,” but her teachers and friends have since pulled her out of her “shy place.”

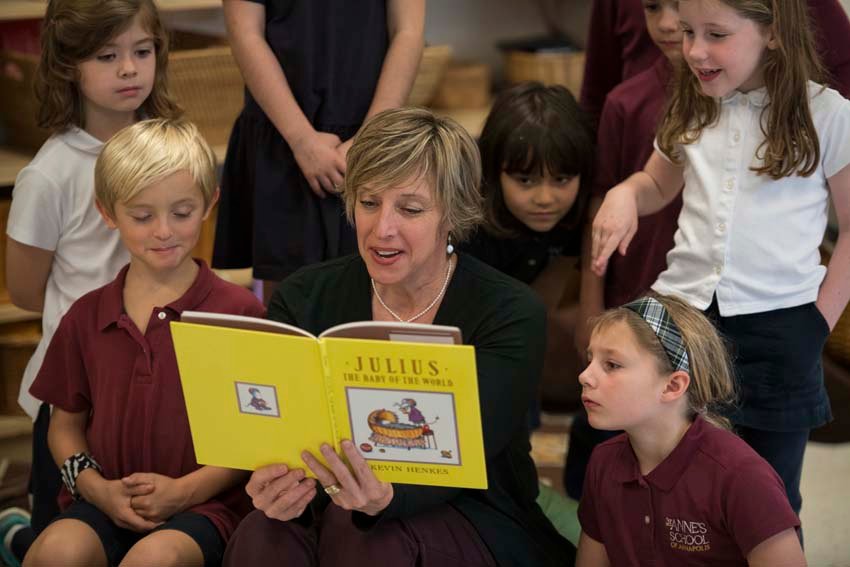

Embedded in the school’s culture is the edict that every human being has worth and deserves dignity. “We want our students to feel safe and known and included,” says Head of School Lisa Nagel. Upon her arrival in 1999, Nagel led the introduction of a progressive curriculum that prioritizes age-appropriate social and emotional learning and conflict resolution skills alongside traditional academics.

St. Anne’s School was founded in 1992 in the Episcopalian tradition, but remains independent of any one Parish and is nondoctrinaire in its religious teaching. “Our goal is to prepare the children to be theologically literate. We’d rather a child go out into the world and have thought about the religious experience of other people and how religious experiences inform all of our political and cultural lives,” says Nagel.

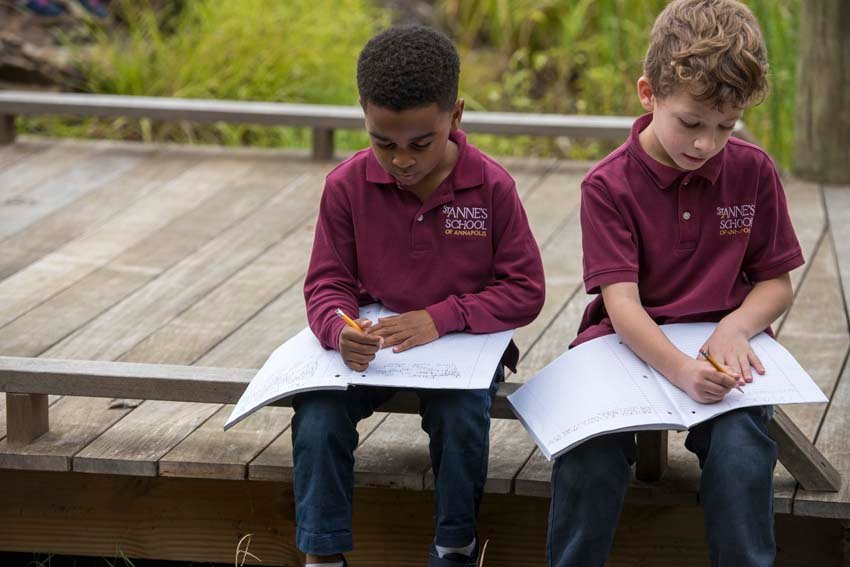

The environment in which students learn and how they learn is just as important as what they learn. The lower school classrooms resemble cozy living spaces. “We’re thinking about the whole child when we’re setting up our classrooms. We’re thinking about classroom climate,” says fourth-grade teacher Detra Watson. Table lamps cast soft lighting on workspaces. Upholstered seating, rugs, and floor pillows complement common desks and chairs. Students move about the classroom as needed during lessons.

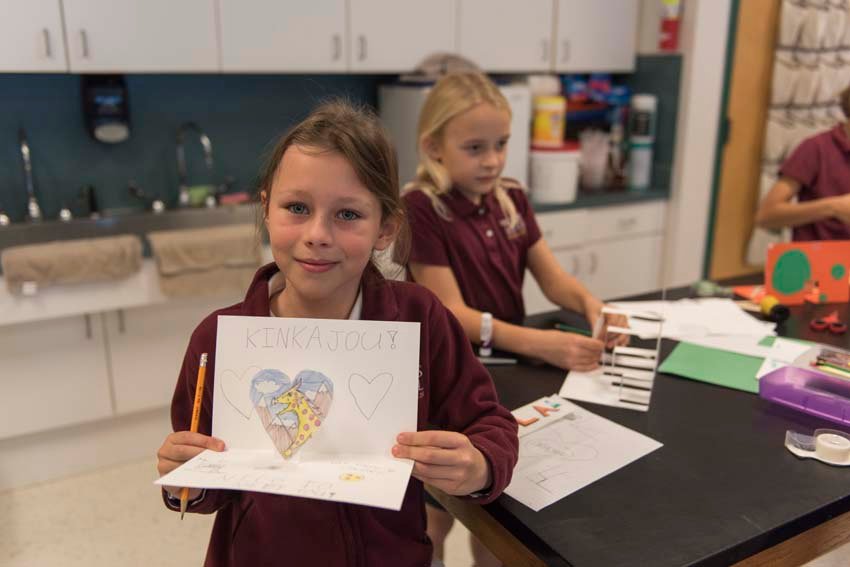

Watson’s class this past school year completed a unit on the Chesapeake Bay, the environment, and the economy. They heard from watermen and seafood restaurant owners about the impacts of water quality and bay restoration on the businesses in their community. “Our hope is that social justice action will take place. We may not have caused a problem, but we’re a part of something bigger and can make change,” says Watson.

Teachers model positive relationships, inclusion, and healthy conflict resolution from the earliest grades. Sully, 10, has personalized his polo shirt by popping his collar. “At a young age they just teach us not to disclude [sic] people. So, you just sort of grow up with that background. You’re taught that, and you still know it,” he says. He shrugs his shoulders as if to say, “It’s just what we do here.” Will and Betty, both 12, and Peter, 11, agree. Sully’s fellow fourth-grader, Alana, says: “It’s more about the person’s feelings. You can’t say, ‘You can’t play,’ so we just find a way to include everyone.”

In fourth grade, all students take an eight-week friendship unit. The school’s counseling and wellness specialist, Katie Streett, who teaches the unit with the fourth-grade teachers, explains how nine- and ten-year-olds are developmentally primed for conflict. “Fourth-graders are moving from being really concrete thinkers to being more abstract thinkers. They’re deciding who they want to be friends with,” she says.

Fourth graders first learn about healthy friendships, and a segment called “peacemaking” teaches students how to resolve interpersonal conflicts—their own and those of others. “The purpose is not to keep conflict from happening, but to give students the tools to use when conflicts arise,” says Streett. Instructors role-play responses to conflicts in class when emotion is not a factor.

Sully remembers a time when he and a buddy used peacemaking skills to resolve their own conflict. “I just reminded him of what we learned in friendship class that day, and we took a step back and looked at the problem we were facing and solved it,” he explains.

Once the students have completed the unit, they practice by performing “peacemaker duty” at recess. They don peacemaker caps so students in the lower grades who might need help can recognize them, and they carry clipboards with reminders of resolution tools. Peacemakers ask students in conflict to stand and face each other. They brainstorm solutions with the students in conflict and coach the children through “I feel” statements so that everyone can express how they have been affected by the conflict. Peacemakers request those seeking help to give each other a fist bump or a handshake before parting.

“We teach the children it is not their job to solve the conflict for someone but to provide the space and guidelines for others to find their own solutions,” says Streett.

Newly acquired peacemaking skills are not only reserved for the playground. St. Anne’s seventh grader Will says he used his peacemaking skills to resolve a conflict at home. His parents were having a debate that got a little heated, and he tried to help calm them down. “I just kinda tried to make them stop and listen to each other because they weren’t talking to each other,” he says. He relates that he was only in fourth grade at the time and could probably do a better job now.

Like many school children, St. Anne’s students admit they have days they would rather stay in bed, and they will tell you candidly how they feel about homework. However, they also admit that they have learned skills and discovered interests at St. Anne’s that they did not have before. Betty and Sage learned that they love playing instruments. Alana now challenges herself to push past her comfort zone. Fourth-grader Peter wants to be an author, and lately he’s been writing a memoir. “I have a habit of writing about friends,” he says. “Friends give you a sense of belonging and personal connection.”

The children will leave St. Anne’s having learned conflict resolution techniques and relationship tools to keep in their toolbox of life skills. Will believes the logical thinking he’s learned in pre-algebra helps him “think stuff out, even if it’s not math related,” he says. The most important thing he’s taking with him, he says: “I feel like it’s kindness, just being nice to everybody. You don’t have to like them or be their really close friend, but you should not be mean.”

Sage graduated from St. Anne’s this past academic year after completing eighth grade, the school’s highest grade. She says she feels academically prepared for high school and then some. She knows because she tested her knowledge on how well she could answer her older brother’s homework questions. She says, “He’s a junior in high school, and I already knew what to do!” █