+ By Susan Moynihan + photography by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Walk into the airy kitchen in Joyce White’s Hillsmere home, and the first thing you’ll notice is the abundance of food on her table and countertops: a pink, three-tiered cake with white scrollwork details in icing; glass sundae cups with layers of blue, orange, yellow, and cream jellies; a tureen-sized potpie, its thick crust browned from the oven; creamy grits paired with a thick slab of sizzled bacon. The only thing missing: aroma.

White is a food historian, and these tantalizing faux dishes are the tools of her trade, made upstairs in a cozy bedroom-turned-office, complete with cookbook-filled bookshelves, a corner workspace with glue gun, resins, and dyes, and stacks of bins containing molds of every shape and size.

While she didn’t set out to become a maker of faux food, food has always been a part of her life. “I’m Italian,” says White. “I used to sit in the high chair, watching my mom and my grandmother cook.” During her junior year at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in upstate New York, where she majored in museum education, she interned at the Geneva Historical Society as an 1840s scullery maid. “I had to learn how to build a fire, tend a fire, on top of learning how to cook on a fire. And I was like, ‘This is what I want to do.’”

Her passion for hands-on education led to a post-college job, in Westchester County, New York, doing cooking demonstrations at a 1780s tavern with a working hearth. In graduate school at Penn State, she earned a master’s in American studies. “Cooking is folk culture,” she says. “You learn by observing. You repeat, you vary, all of those things. I did a lot of my research papers on food.”

Upon moving to Annapolis in 1997, she enrolled her three-year-old at St. Anne’s Preschool for the Arts (formerly Preschool for the Joyful Arts) and started volunteering there. After that, she taught as adjunct faculty at Anne Arundel Community College. But it was Riversdale House Museum in Prince George’s County that brought her back to the kitchen. This circa 1800 Georgian plantation, once owned by Rosalie and George Calvert, is a National Historic Landmark and a National Park Service National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site.

White’s job was to use food to showcase all aspects of life there, from what the owners and family ate to the enslaved people who prepared and served everything. With assistance from the museum’s volunteer Kitchen Guild, she taught open-hearth cooking classes and prepared the food served at special events. When she left the full-time role, she stayed on as consulting food historian. She’s currently the vice president at Hammond-Harwood House and is a nationally recognized consultant on food history. Most recently, she appeared on CBS Sunday Morning, talking about Baltimore’s connection to fudge.

Being a food historian means understanding not just what our predecessors ate, but how food affected their daily lives, from sustenance to status. As White walks through the faux dishes displayed on her dining room table, she points out a wax swan adorning the thick-crusted potpie. The pastry functioned as the soup vessel, and the wax figurine served two purposes—to look pretty and to show what type of meat was inside. “Yes, they ate swan,” she says. “They ate anything they could catch.”

The more abundant the table display, the richer the family. Elaborate meals fed family and guests but also showed that the host had the financial resources for the feast. Pointing to the sundae cups layered with blue, green, and cream gelatin, which we think of as simple today, she says, “You couldn’t just go buy a package of instant gelatin; you had to boil eight calves’ feet or import the air bladder of a sturgeon to do all these incredible things.”

Richness of color was equally important. Hues came from natural ingredients: green from spinach juice, purple from syrup of violets, yellow from turmeric or saffron. Anything pink and red used cochineal. Made from the dried shells of the beetle of the same name, this red dye had long been held in high status in English society and was originally reserved just for royalty. The same beetle insect dye that made pink icing was also used for clothing, including the Redcoat uniforms of British soldiers in the Revolutionary War.

Enslaved people and indentured servants made the meals, not estate owners. Kitchen staff would learn recipes from older cooks and share techniques and traditions with workers brought in from neighboring estates when more hands were needed for gatherings. If someone in the kitchen was literate, they might read aloud a cookbook recipe to get everything started. But recipes were suggestions at most, says White,“either a list of ingredients with no measurements or directions, or just directions and a partial list of ingredients.” This allowed for a lot of interpretation and adaptation, and that is what created our regional cuisine.

“Early foundational cuisine is really a melding of all these traditions together,” she says. “It’s this British base with a huge overlay of Native American local produce.” The German influence was brought down from settlers in what is now Pennsylvania Dutch Country. French techniques came via classically trained chefs of area Francophiles, including Thomas Jefferson. White had heard the rumor of the Founding Father’s French chef giving lessons to enslaved cooks but said that it could not be proven or disproven. What is clear is the key impact of the seeds and plants brought over on slave ships from the African continent and beyond. “One of the huge contributions that African Americans made in terms of spices would be cayenne pepper—hot, spicy pepper. Brits did not bring that.”

For the upcoming 250th anniversary of the building of Hammond-Harwood House, White is writing a companion book to Maryland’s Way: The Hammond-Harwood Cook Book, which was created in 1963 and contains recipes that date back to the 1760s. She’s selecting recipes that can act as springboards showing the foundations of Maryland’s cuisine and the older traditions from which it has evolved.

You can see the foodways in other dishes. Take stuffed ham, which is still commonly served during the holidays in rural Southern Maryland. It’s a traditional British dish, corned ham, but moistened with kale and flavored with spices such as mustard seed, black pepper, and cayenne. “That’s probably because it was devised by enslaved people in St. Mary’s County,” she says.

For White, it’s imperative that her designs show all types of dishes, reflecting the everyday disparities. Alongside her elaborate cakes and puddings are perfect replicas of more humble dishes that would have been eaten by the poor and enslaved: johnnycakes, hominy grits, slabs of bacon. Meat, be it livestock or wild game, was limited by seasonal availability. The ingenuity of making the most of what’s available is still evident in regional staples such as scrapple, a variation of traditional liver pudding. “You slaughtered once a year, so you need to make it last,” she says.

For much of her career, White had purchased museum-quality food replicas from Texas artist Henri Gadbois. When he passed away in 2018, she turned to her collection of antique molds, many of which are stored on a six-tiered wooden shelf that runs the length of a wall of her basement. Her wide variety of pieces—made from tin, cast iron, pottery, and creamware—spans eras, some dating back to the early nineteenth century. Some of her faux food works are displayed at Hammond-Harwood House and Riversdale House. She’s also done commissions for historical projects in places including Tennessee and Yorkshire, England.

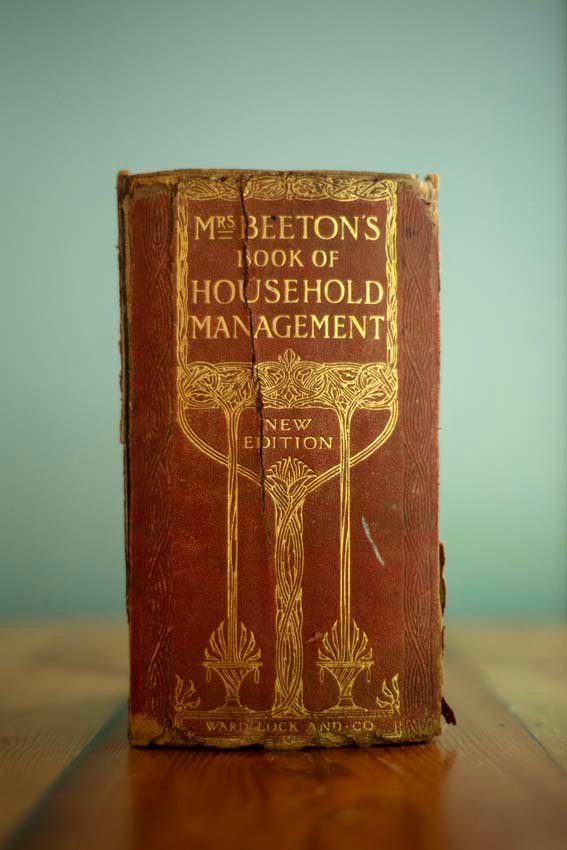

For her faux food, she recreates an actual dish, replacing edible ingredients with silicone or resin to create a base, and then decorates from there. Design ideas come from period cookbooks—her oldest is a 1912 reissue of Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, originally printed in the 1860s—and her collection of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century recipe booklets, advertising promotionals for gelatin and baking companies. Her creation process is trial and error, with a little help from YouTube, if needed. “Anything made in pottery, I have to use silicone, because the resin will stick,” she says. “Anything made in a silicone mold, I have to use resin or clay.” She uses spackle to give realistic icing texture to Styrofoam® cake bases and creates her own molds by pressing existing details into blank trays of silicone. She also takes advantage of modern dyes and food colorings, so no crushing of beetles is necessary. It’s much like cooking; if the recipe doesn’t come out, she starts over, and over, until it’s where she wants it to be.

Getting hands-on with period cookware gives White’s work added meaning. “Coming from museums, you don’t touch anything without wearing gloves,” she says. “So, to make even the faux things using these pieces—I feel like I’m honoring tradition, really touching all these different elements of social history and all of these simple things, especially as a woman, that really affected the development of the kitchen.”

Offering programs for private groups, from guided chocolate tastings and presentations on colonial dining to teas and spirits, White brings learning experiences to life. She also shares a treasure trove of recipes on her site. █

For more information, visit atasteofhistory.net.