+ By Desiree Smith-Daughety + Photos by Kaitlyn McQuaid

The intention behind Forward Brewing is in its name. Cam and Claire Bowdren opened the Eastport-based nanobrewery on May 16, 2020, with the mission of moving forward. They may not have bargained on chewing through the leathery red tape of opening a restaurant and brewery without a law that supports small breweries selling directly to taproom customers—it was such a challenge that they almost gave up on the idea. Almost.

However, Cam—who conditioned his patience muscle during his seven years as a teacher—wanted to proceed 15 years ago, so he and Claire played the long game. Their LLC was set up in 2018, followed by a two-plus yearslong hurry-up-and-wait period. They got their approval just in time for the COVID-19 pandemic’s attendant shutdowns. Versed by then in the vagaries of business, they implemented immediate pivots to ensure that their long-sought dream became a successful venture.

Forward Brewery’s location works in their favor. Just a short jaunt over the Spa Creek Bridge from downtown Annapolis, it is located in Eastport, where it receives an abundance of foot traffic. Customers can move easily between restaurants and local shops. The building and property—a former marine electronics business before it was relocated to a nearby marina— has been family-owned for over 30 years.

The nanobrewery is the Bowdrens’ vehicle for investing in the Annapolis area to realize their vision of the type of place that they want to live and grow in. Their motivation is to keep people rooted there. The couple met while working together at Vin 909 Winecafé, and they conducted their research by experiencing the different craftsmanship in beer making in cities such as Raleigh, Asheville, Richmond, and both Portlands (Oregon and Maine). As breweries have proliferated in these areas, the Bowdrens decided this was something they could do.

Cam, who started out as a home brewer, says that there’s an art and a science to brewing that he was ready to learn. He spoke with other brewery owners and got input, finding that the information was readily shared. “Beer is the easy part. It’s the business part that’s the challenge. Dealing with the city, county, state,” he says. “I think local brewers are all in a constant state of learning and education.” Per Cam, there aren’t solid definitions for what constitutes a nanobrewery. Generally, up to seven brewing barrels is nano-sized, while a microbrewery may be anything above that amount.

Head brewer Warren Hendrickson has brewed professionally for 10 years, with experience at five breweries, the first in Upstate New York, where he’s from, at the Lake Placid Pub & Brewery. He had relocated to Maryland to work for Flying Dog Brewery in Frederick before connecting with Cam through a brewer’s job website about three years ago, and joined the Bowdrens to help build the business. Like Cam, Hendrickson started with home brewing, making five-gallon batches on the stove and testing what worked and what didn’t. Intrigued by brewing’s creativity, he moved into it as full-time work. “Starting out, brewers apprentice under a head brewer and work their way up from there, then bounce around, learning stuff. It’s a lot to take in, a mishmash of creativity in writing recipes, chemistry and engineering, working with heavy machinery, and pulling all those skills together,” says Hendrickson.

Forward Brewing has six big tanks, called fermenters or fermentation vessels, that are stacked vertically in twos as to best use the tall, highly organized space. “We’re constantly cleaning in brewing,” says Hendrickson. “The joke is, we’re glorified janitors in the brewery, moving liquid from one vessel to another, rinse and repeat.” He prefers the small-batch style of brewing because he can try out many recipes. Product moves quickly, with a keg ready in two weeks before it is sold out in three to four weeks’ time. It takes about a day to brew a batch, which ferments for a week. It then requires a week of conditioning time including chilling it down and carbonating it, resulting in a quick turnaround, generally. The COVID-19 pandemic shifted sales from on- to offsite, for which they set up a small canning line to manually fill and label cans one at a time.

Every batch brewed has its own unique quality. The yeast strains contribute to an evolution of the beers within a style, so if one of Forward Brewing’s regulars were to drink a beer made with the Belgium yeast strain, then they would be able to tell the difference between batches. “With every beer, there’s an opportunity to learn that style,” says Cam. “With our employees, we’ve had low turnover, so when we revisit styles, we’re able to talk about the differences between what we made before and what we’re doing now. The same with food. We’re expanding. We have a small, open kitchen and have honed our style in it.”

While many breweries in other counties only offer beer, with perhaps an invited food truck nearby, Forward Brewing maximizes its open-concept kitchen space through creativity in the types of foods offered. “With trucks, there’s a lot of fried food, says Cam. “We can be more dynamic and offer a range of options, including selections for vegetarians.” Claire, who has a master’s degree in public health with a focus on human nutrition and sustainable food systems, adds, “We try to meet the diverse tastes of our customers. We also try to offer dishes that can be shared or enjoyed on their own.”

Claire believes that the food part of the business is where they can be most environmentally sustainable. Their aim is to reduce their environmental footprint by buying from local suppliers: produce and cheese are sourced from Easton; pork and mushrooms are from Edgewater farms; and fish and crab are from Chesapeake Bay. Their sustainability efforts also involve composting food and kitchen waste, using compostable plastic cups, and working with the company Annapolis Compost, which distributes their decayed organic matter to local farms.

To balance water usage, they financially support local environmental organizations and foster oyster cages. They have also recently begun lending a literal hand by helping to “plant” baby oysters based on the amount used. It’s one cent per baby oyster, and a healthy oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day. Forward Brewing’s beer label states, “This beer cleans our Bay by planting oysters.” Recycling practices are also prominent. Cam built community-style tables from barn boards salvaged from a local farm, made the bar from reclaimed wood, and repurposed the building’s pre-renovation shelving. The company logo is made of recycled copper. Noticeably absent behind the building is a dumpster, as they create only one tote or bin of trash per week.

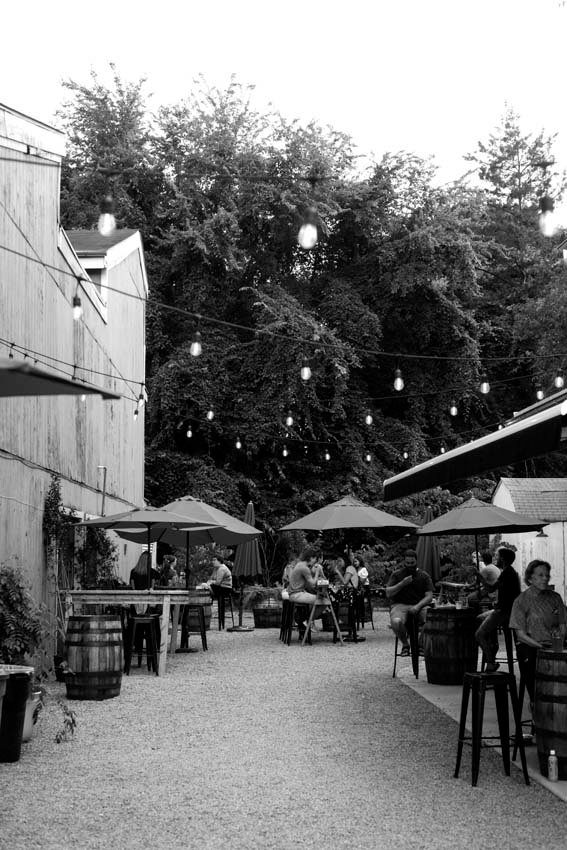

Skylights and plants give the space a homey feel, as if you have popped in to your neighbor’s house to share a glass or two. Upended empty whiskey barrels (which were donated) serve as tables in the outside courtyard. The front wall and windows are original to the building, so it retains a historic feel, while the interior has been upgraded with sustainability in mind.

The Bowdrens are further giving back to their local community by donating funds to Eastport Elementary School, Annapolis Middle School, and the EWE Spirit Foundation as well as host fundraisers for Annapolis Pride, the Anne Arundel County Public Library Foundation, and other groups on a regular basis. They also host weekly running and cycling clubs so that patrons can burn the calories they’ll consume afterward.

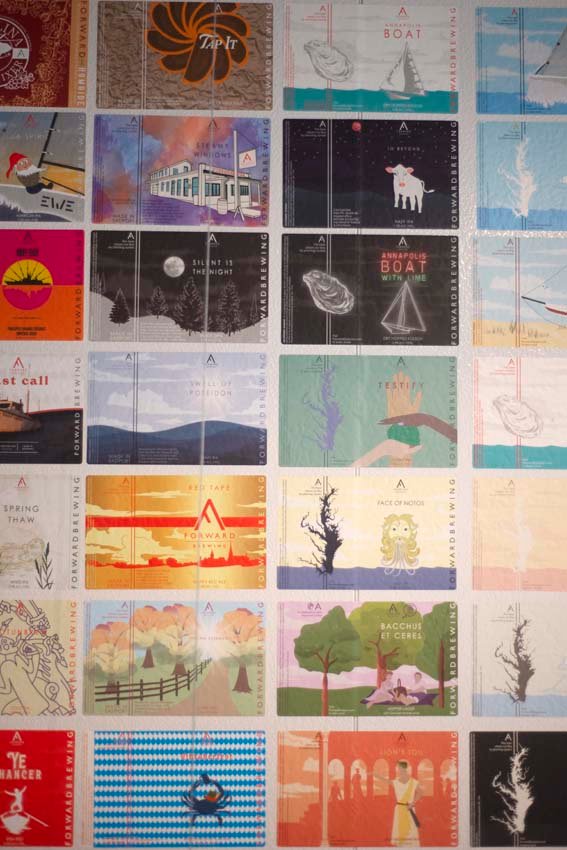

With businesses now back to nearly normal operations, Forward Brewing sustains a taproom as well as offers cans to go, along with crowlers (32-ounce cans), howlers (32-ounce glass bottles), and growlers (32- or 64-ounce airtight beer vessels often made of glass or stainless steel). One of their regulars has become their designer and collaborated with local photographer Jay Fleming to design the label for its Last Call beer. The labels resemble historic oyster can labels, which were their inspiration. All employees pitch in when naming beer.

Forward Brewing’s flagship beer Annapolis Boat was its first offering. It’s a Kölsch with a light style that is run for nine months of the year and continues to be the bestseller. During the other three months, Dry Dock, a toasty lager fitting for the winter season, is featured. The Bowdrens are responsive to customer feedback and are especially proud of a bitter they made—many customers said it tasted as if it came from a pub in England and that Hendrickson had nailed the style. Depending on customer response, they may repeat a particular recipe once a year. With 12 taps available, they can maintain a diverse selection of offerings, such as an IPA, a sour, barrel-aged beer, porter/stout, Irish Red lager, amber, and a fall-season Oktoberfest. They also brew fruity beers, Belgian styles, and more. “We want to have the excitement of new beers,” says Cam, “but also have those that customers can revisit.” █

For more information, visit forwardeastport.com or follow

@forwardbrewing on Instagram.