+ By MacDuff Perkins + Photos by Mary Ella Jourdak

When Annapolis-area photographer Mary Ella Jourdak was in the second grade, her mother pulled her out of school one day to wander the halls of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Jourdak was entranced by the colors and textures of the paintings hanging around her. Her mother singled out one particular painting, Vincent van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters, but Jourdak didn’t share her mother’s appreciation.

“I thought, ‘This is really ugly,’” she says. “I didn’t get it. And my mom told me, ‘It doesn’t have to be beautiful for you to love it.’” This sparked an epiphany and imprinted on Jourdak. She realized she didn’t have to play by the rules if she committed to authenticity. And above all else, Jourdak craved authenticity.

When she was a teenager, the social constructs and stipulations of middle school on Maryland’s Eastern Shore created roadblocks in Jourdak’s education and made her feel uncomfortable. With the support of her parents, she homeschooled herself for a year. “I fully isolated myself in my interests,” she says. She dove into mythology and Impressionist art, astrology, and Latin. The education was unorthodox but impactful, and Jourdak thrived. In high school, she fell in with an art crowd. Teachers recognized her talent and encouraged her on her creative path. A self-described hermit, she developed the courage and confidence necessary for artistic expression.

Jourdak had a lacrosse scholarship to the University of Maryland when she spontaneously decided to take a trip to Savannah with her mother. The secret squares draped in the Spanish moss spoke to her, and she felt that she belonged there. “For years, I was a very different fish swimming in this pond,” she says. “I went down to Savannah and realized there was a whole aquarium full of fish like me.”

To offset private school costs, Jourdak spent two years at Anne Arundel Community College and transferred the credits to Savannah. Her time at Savannah College of Art and Design fed her with the chaotic energy of expression. “You learn as other artists bring their art to life through their own processes,” she says. “It’s nonstop inspiration to get off your butt and create more.”

After college, Jourdak worked as a wedding and elopement photographer outside Savannah, on Tybee Island. “In some ways, I had to pick the battle of what I wanted to focus on,” she says. “The nature of portrait photography forced me to step out of my comfort zone and throw down my own barriers. When you show up as your full, authentic, ridiculous self, people mirror that.” She photographed weddings, elopements, family portraits, and more, learning how to make others feel comfortable enough to be vulnerable in front of her lens. “I think my greatest skill is listening,” she says. “I want to know how my clients want to be seen and heard. But this goes beyond photography; this is how you should feel every day.”

Within three years, she felt that the Tybee Island market was oversaturated and returned home, where she recognized her ability to act as a change maker. The awkwardness and alienation she felt in her younger years were things she would never wish on others, so she committed to making her clients feel safe and comfortable in her presence. “I focus on love in all its different forms,” she says. “I think we struggle to create inclusive spaces, and it’s a lot of work to become more accepting and loving. But it’s a worthwhile fight to pursue. This sometimes makes people angry, but it’s helped me to stand up and speak out.”

This gives her moments of primal joy. Shooting solo, Jourdak pulls roughly 5,000 shots at each wedding, running around like a pinball, finding moments to capture and feeding directly off the energy of her subjects. “The First Looks are absolutely magical, with all the pent-up anxiety and joy,” she says. “I’ll set the groom up first, put them in position and . . . I’ll say, ‘You look amazing,’ have them chill. ‘You’ll know I’m coming, but under penalty of death, do not turn around.’ Then . . . the bride comes in, super hyped. I’ll tell the bride, ‘Tap your partner on the shoulder and say I’m here now.’ And I cry every time.” She’s usually not the only one crying.

Jourdak also bring such moments to her family. One of her most meaningful projects was photographing her cousin, beginning with newborn photos. They took on a different significance when her cousin developed a brain tumor, and Jourdak recorded her cousin’s short life before she passed away just eight years later. “Being the [family] record keeper is intense,” she says. “There are a lot of beautiful, fulfilling moments, with lots of upsetting ones.”

She notices when a client has logged into her photo database and downloaded a photograph of an older relative. Inherently understanding the pain of loss and the solace found in family portraiture, she’ll reach out to the client to check in and reconnect.

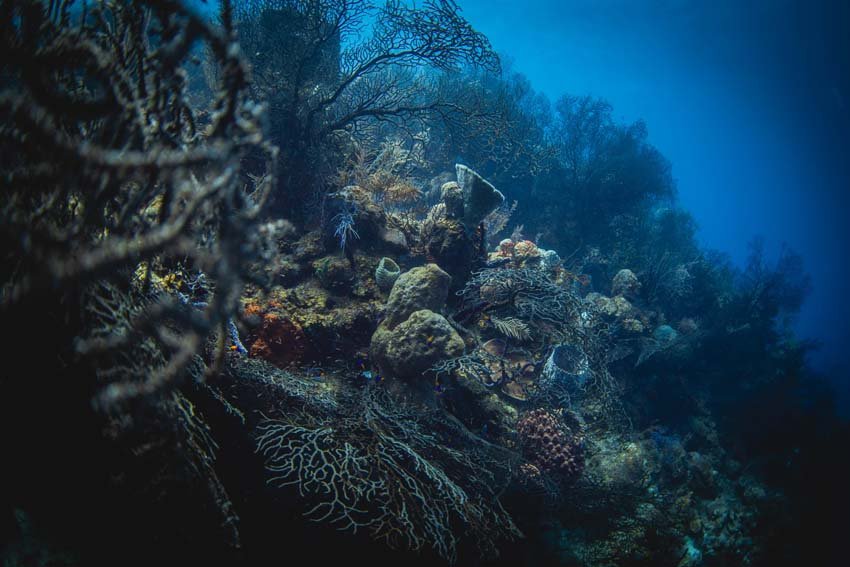

When she’s not photographing people, Jourdak’s sense of wanderlust drags her across the globe, chasing new experiences and broader horizons. “I love those fish-out-of-water moments,” she says. “It’s such a gift to be able to run off, jump into another life, and moonlight as somebody else for a little bit.” There was the culture shock of Japan, the underwater enchantment of the Galapagos, diving in St. Croix, and much more. She came home from Turkey with a suitcase full of olives. Perhaps her favorite experience was in Iceland, seeking out the aurora borealis. “I slept in a car for a week,” she says. “I’d hike all day, find a local pool to swim in, then learn from villagers what the forecast was for cloud cover.”

Today, Jourdak splits her time between travel and photo sessions. “Being alone and being assured in how I’m shooting fills my personal battery back up and gets me ready to go shoot other people,” she says. “My mantra is: kick ass and make the art you love.” And with the click of a shutter, that’s what she does. █