+ By Brenda Wintrode + Photos by Jay Fleming

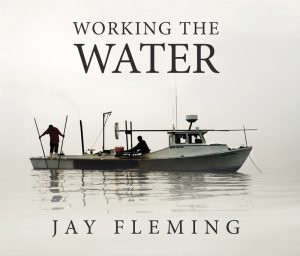

We see workboats from the shore of the Chesapeake Bay. Watermen balance crab pods on the wide, flat roofs of deadrise boats putting along from one buoy to the next. Barcats make their way down shallow creeks and deliver a fine catch to a dockside restaurant, where we will dine on the spoils next Friday night accompanied by a frosty pilsner. These are familiar scenes to Maryland’s residents and seafood consumers. But what we don’t see is the effort and resources it takes to catch the rockfish, perch, crab, or oyster that come to be on our plate. Someone plucked it out of the Bay, but with what? From exactly where on the Bay? How was it cleaned and processed? Photographer Jay Fleming brings us inside the reality and the beauty of the Chesapeake Bay’s seafood industry in his new photography book, Working the Water, October 2016.

We see workboats from the shore of the Chesapeake Bay. Watermen balance crab pods on the wide, flat roofs of deadrise boats putting along from one buoy to the next. Barcats make their way down shallow creeks and deliver a fine catch to a dockside restaurant, where we will dine on the spoils next Friday night accompanied by a frosty pilsner. These are familiar scenes to Maryland’s residents and seafood consumers. But what we don’t see is the effort and resources it takes to catch the rockfish, perch, crab, or oyster that come to be on our plate. Someone plucked it out of the Bay, but with what? From exactly where on the Bay? How was it cleaned and processed? Photographer Jay Fleming brings us inside the reality and the beauty of the Chesapeake Bay’s seafood industry in his new photography book, Working the Water, October 2016.

Fleming presents an educational tour of what it takes to earn a living on the water, fishing the Bay, throughout the four seasons. Working the Water opens in the spring. Fyke nets are laid in the shallow waters of a creek at daybreak to capture anadromous yellow perch. Watermen in bright orange rubber coveralls pull gill nets full of rockfish into a small wooden dinghy on the calm, brackish Virginia water. A turtle opens his jaw wide on the deck of a turtle fisherman’s boat as if protesting his capture—indeed, snapping turtles are caught, processed, and exported from Chesapeake waters. This and many other little-known facts about the industry can be found on page after page of Fleming’s book, which came out in October.

Fleming not only captures the harvest but also its reapers, some of whom are fourth-, fifth-, and even eighth-generation watermen. Over a three-year period, Fleming formed relationships with watermen up and down the Bay. One fisherman would vouch for him to a boat builder, a net weaver, and a muskrat trapper. Over time, they allowed him, his kayak, and his diving gear onto their boats to document their work, and he immersed himself in their world. He explains his motivation behind the project: “I wanted to show people how it’s done, not just show pretty pictures of the Chesapeake Bay.” The result is an encyclopedic time capsule that encompasses the details of a waterman’s efforts on the murky Chesapeake. Fleming gained a tremendous respect for their knowledge of fish population fluctuation, fishing techniques, business savvy, and ever-pertinent weather predictions. “To me, they are the most knowledgeable people on the Chesapeake Bay.”

Fleming not only captures the harvest but also its reapers, some of whom are fourth-, fifth-, and even eighth-generation watermen. Over a three-year period, Fleming formed relationships with watermen up and down the Bay. One fisherman would vouch for him to a boat builder, a net weaver, and a muskrat trapper. Over time, they allowed him, his kayak, and his diving gear onto their boats to document their work, and he immersed himself in their world. He explains his motivation behind the project: “I wanted to show people how it’s done, not just show pretty pictures of the Chesapeake Bay.” The result is an encyclopedic time capsule that encompasses the details of a waterman’s efforts on the murky Chesapeake. Fleming gained a tremendous respect for their knowledge of fish population fluctuation, fishing techniques, business savvy, and ever-pertinent weather predictions. “To me, they are the most knowledgeable people on the Chesapeake Bay.”

Fleming considers himself an environmental photojournalist and a fine arts photographer: “I like to show how humans interact with the environment.” He captures the mental and physical toughness of the fishermen, who are up before the dawn and still manage to smile through beards covered with frozen chunks of snow. Fleming, too, was there, and shared those hardships with them for a time. He took many shots from his kayak in frigid waters to fully capture the scene, and has considered what it would have meant if he had tipped. “At times, it was scary because of the weather,” he recalls. Luckily, he was able to capture events from rarely seen perspectives without incident.

Fleming considers himself an environmental photojournalist and a fine arts photographer: “I like to show how humans interact with the environment.” He captures the mental and physical toughness of the fishermen, who are up before the dawn and still manage to smile through beards covered with frozen chunks of snow. Fleming, too, was there, and shared those hardships with them for a time. He took many shots from his kayak in frigid waters to fully capture the scene, and has considered what it would have meant if he had tipped. “At times, it was scary because of the weather,” he recalls. Luckily, he was able to capture events from rarely seen perspectives without incident.

Three men pull in the ropes of a haul seine heavy with gizzard shad. Their faces are strained; the last man is leaning back as if he is the anchorman on a tug-of-war team. They are not just pulling in shad, but also their paychecks. An oyster shucker is in a yellow rubber apron and safety goggles; he is covered in a gray-brown splatter of carrion. Exposure to harsh winds is evident on the faces of seasoned watermen. Pensive gazes—or perhaps apprehension—on young faces are revealed. The photos are as vibrant as they are informative, and as shocking as they are reverent.

Three men pull in the ropes of a haul seine heavy with gizzard shad. Their faces are strained; the last man is leaning back as if he is the anchorman on a tug-of-war team. They are not just pulling in shad, but also their paychecks. An oyster shucker is in a yellow rubber apron and safety goggles; he is covered in a gray-brown splatter of carrion. Exposure to harsh winds is evident on the faces of seasoned watermen. Pensive gazes—or perhaps apprehension—on young faces are revealed. The photos are as vibrant as they are informative, and as shocking as they are reverent.

Both of Fleming’s parents influenced his career choice. His father, Kevin, was a professional photographer with National Geographic and taught Fleming how to shoot with his first camera, a Nikon N90s. Eliminate the horizon line, his father would say, consider composition, find a clean background, and use the light as one would use a verb in a sentence. Fleming’s mother, Carla, worked for the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), where Fleming had two internships in high school, assisting with spawning fish surveys in the Bay. He brought along his camera, and the pictures became documents used by the DNR for public education.

In that same vein, Working the Water is an educational instrument as much as it is a work of fine art. Fleming’s ultimate goal is to educate the public. “I want people to know how much goes into it. When we buy a dozen crabs, the price can be shocking. But when you see what goes into it, you understand.” █