+ By MacDuff Perkins + Photos courtesy of Erika Robuck

Bestselling-author Erika Robuck has a knack for uncovering hidden women. The Annapolis native, whose seventh historical fiction novel will be released in August, has written about rumrunners, code breakers, covert operatives, poets, and socialites—all women who played significant roles in history while maintaining a distinct level of anonymity.

On shelves next to Kristin Hannah and Elizabeth Gilbert, Robuck’s novels are known for their exacting research and compelling storytelling. She unearths history from the archives and exposes it to a modern audience, retelling it from the perspective of the women who lived in shadows.

She developed her love of storytelling from other important female figures in her life. First, her Irish grandmother gave her a love of reading. She was lost in the universes of Maeve Binchy and Frank McCourt, E. B. White, and Mildred D. Taylor. Later, in Catholic school, a nun pushed her to focus not just on the words on the page but also on her own. “Sister Francis,” she says. “She was so scary, but boy could that woman teach English.”

Robuck pursued creative writing at Villa Julie College (now Stevenson University) but chose it as her minor. Her major, instead, was education. Later, as a schoolteacher in the Annapolis area, she found her passion connecting students with the world of learning. “I teach to be interactive with the living,” she says. “I write to be with dead people.”

Her own writing took a turn after she read Toni Morrison’s Beloved. “That was the one that woke me up to the fact [that] fiction allows us to experience the emotions of the people experiencing the history,” she says.

Her first novel came to her during her first maternity leave. A friend had been on vacation and showed her some pictures of ruins on the island of Nevis in the Caribbean, and Robuck was captivated. She began to independently research the area and found a compelling story, immediately becoming obsessed. “It had everything I loved: a ghost story, history, and Annapolis.” While her infant son napped, Robuck wrote. And after three years, she held her first novel in her hands.

If the writing process was arduous, looking for representation and a publisher was brutal. She sent out 100 letters and received 100 rejections. But she was given helpful feedback, which she used, and decided to move forward.

Self-publishing her first novel about a hidden connection between an abandoned Nevis sugarcane plantation and an Annapolis woman, Robuck earned excellent reviews for Receive Me Falling, which gave her the opportunity to attend author events and festivals. She set up a website and a blog to connect with readers and started looking for her next novel.

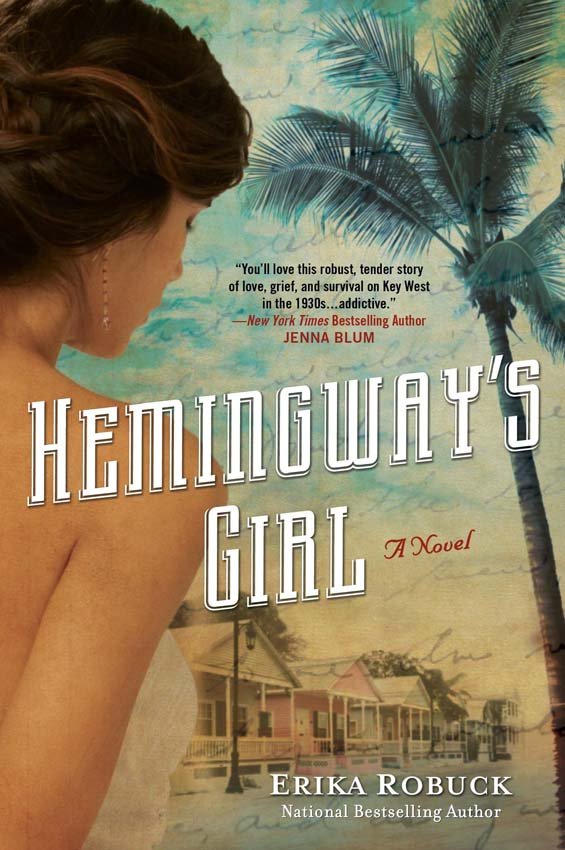

She stumbled upon her next protagonist while on a family vacation. “When I get obsessed with something—when it’s all I can talk about, read about—that’s when I know I’m onto something,” she says. In Key West, walking the rooms and halls where Ernest Hemingway once lived, she felt herself stepping back in time, listening for the men and women who surrounded the tortured writer. She picked up the trail of a single housemaid, and Hemingway’s Girl was conceived. This time, representation was a breeze.

As any historian knows, our stories do not exist independently but are instead linked in the long chain of time. When Robuck found Hemingway, she also found Zelda Fitzgerald, the wife of F. Scott. This research led to her next book, Call Me Zelda, and to the literary culture of bohemian poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. On the book tour for Fallen Beauty, she toured Concord, Massachusetts, and walked through the home of Nathaniel Hawthorne. There, she found the voice of his wife, Sophia, and The House of Hawthorne was conceived.

At this point, Robuck was gaining a reputation as a skilled author, but her agents had feedback. “I wrote a whole piece about Bram Stoker’s wife, Florence Balcombe, and that got rejected,” she says. “One of the editors wanted me to write a book about someone who’s remarkable in her own right, and not because she’s a Mrs.” So Robuck began searching for that woman. She stumbled upon the story of Virginia Hall, a Baltimore socialite who became a spy during World War II. “If I had made it up, nobody would have believed it,” she says.

Robuck’s last three novels—The Invisible Woman, Sisters of Night and Fog, and The Last Twelve Miles—all portray women working in resistance and intelligence. These span from the Roaring Twenties to World War II, with her latest novel culminating in the life of war photojournalist Dickey Chapelle.

“Women were able to do more than men,” she says, noting that her stories’ heroines are generally older women and that their age often offered a cloak of public invisibility, allowing their work to go undetected.

Robuck is in good company with her strong protagonists: she’s disciplined and secretive. A mother of three, her craftwork begins as soon as the house is quiet—her husband goes to work; her youngest son is in high school at Archbishop Spalding. Robuck spends time in prayer and meditation, then begins writing at 8 a.m. She stays at her desk until 1 p.m., when she breaks for lunch and a long walk to collect her own thoughts. The afternoon and early evening are spent with her family, followed by some light edits and emails to herself with new ideas. The next morning, she finds herself picking up the strand where she left it, creating the longer pattern of story. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when the house was full, she found a small cottage on the Severn River where she could burrow in and work.

Her approach to research is a process of discovery and illumination. “I’ll find one name, and I’ll look for the domino effect,” she says. “When you’re writing about women living in the shadows, it’s hard to find a paper trail. But once I do, I ask, ‘Where is the story, here? Where’s the theme? What am I trying to reveal?’”

That revelation is at the heart of Robuck’s calling as a writer. “Like Flannery O’Connor, my faith nourishes absolutely everything,” she says. “People don’t understand the contribution that they’ve made. But each of us matters. Each of us is a stone dropped in water, and the ripple effect is profound.”

While Robuck is uncovering hidden heroines, she wants her readers to know that their own stories are just as critical. “Each of us is created for a purpose,” she says. “Whether that is to be a poet or a spy for the Allies, we have been given a vocation. And if you realize that, you can change the course of the world.”