+ By Dylan Roche + Photos courtesy of Bob Spore

To the casual viewer of a TV show or movie, a coffee cup, a police badge, or a ballpoint pen may seem like an insignificant detail in the background. However, those elements have been carefully curated by behind-the-scenes artists to tell a story. These artists handle all the set dressings and props that an actor interacts with throughout the course of the story. Annapolitan Bob Spore, who has built his career working in the art departments on these film and TV sets, knows that a lot of work goes into this part of production. A lot of work.

“You fabricate, you shop for, you do research for, you actually work the props on set with the actors, you will problem-solve and troubleshoot any kind of issues you have with whatever props you are using for such a scene,” he says. “Sometimes you have to come up with ideas right there, on the fly.”

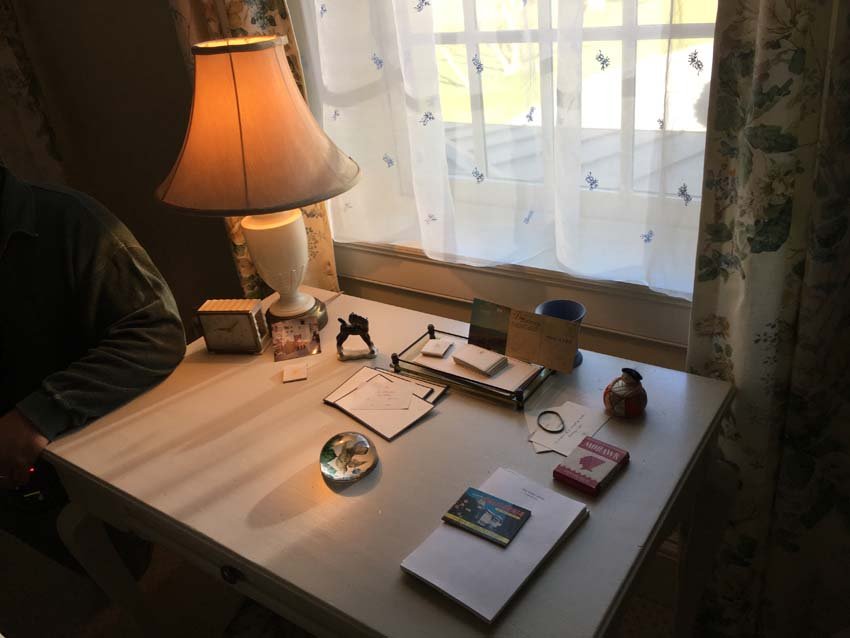

Spore’s credits include such prestigious TV shows as The Wire and House of Cards, as well as films such as National Treasure, Live Free or Die Hard, and Body of Lies. He’s done a little bit of everything since he entered film and television in the late 1990s, but most of it has been in props and sets. Sets include any objects that are there to make the scene look more believable. “If an actor picks up something on the set and uses it in an action, it’s a prop,” says Spore, “and it stays a prop, even if he sets it back down.”

Working within the art department requires much attention to detail, creatively and practically. The work starts as soon as Spore and his team receive the script, which mentions props either through the spoken dialogue or the stage directions. When the script mentions a prop, Spore must decide what it will look like and how it’s acquired, often with input from the director.

“If the script mentions a book, and the director wants a certain book featured, then the props department would need to go get clearances for that book,” he says. “Same with any product placement items.” If somebody pulls out a bottle of whiskey, for example, the props team must figure out what type it will be—a real brand or a made-up one. He notes that the props department will sometimes do what’s known as greeking the label, in which branded material is changed enough so that it’s recognizable but doesn’t cause any legal issues.

If characters are consuming food and drink on-screen, then the props team is responsible for the continuity from shot to shot. “Props has a constant challenge to make sure that the drink level is correct,” he says.

They are also responsible for character pouches, which contain the personal items that the actors wear whenever they are on camera. These might include a watch, a ring, a badge, a gun, and a cellphone. “That’s all part of an actor’s prop character,” says Spore. “So, other than the actual costume he wears, everything else—the name tag, the badges, the belts—that’s all props. It’s technically not a prop, but it is, because it’s on the actor. It might not ever be touched by the actor, but it’s on his person, so it’s part of his character.”

The process always must move one step ahead of the scene that’s being shot—while an assistant prop master works with the talent on set, the prop master prepares for scenes that will be shot in upcoming days, collecting or making props so they can be delivered to set. An experienced prop master, Spore knows that this management role involves working more closely with the director and the script, but the entire effort is collaborative. “It’s a working relationship between the head of the department and the assistants,” he says. “You divvy out the jobs. I may be procuring certain props through shopping or through prop houses, but then I may have a prop assistant who’s very good at fabricating, which means making props from scratch. Or we may have to buy something or find something online and then convert it or change it around to make it suited to the script.”

Spore has been in the entertainment industry for most of his adult life. He established a name for himself in the Annapolis area as a musician, playing with such bands as Social Hour, Ten Times Big, Bulk Mulch, and the Indictments. He also worked at the original Paul Reed Smith guitar factory located on Virginia Avenue in Annapolis throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

At the same time, he was gaining professional skills as a stagehand at several prestigious music venues. “It’s all hands-on,” he says. “You can go to a lighting school or you can go to a film school if you want to become a cameraman or a lighting director, but my skills were all learned on the job—most were learned in the theater.”

He credits his involvement with International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) for making his career progression possible, as unions are what ensure safe work environments. “Had I not gotten into union work with IATSE, I wouldn’t have been able to make that step into IATSE for film,” he explains. “It’s paramount. I’m able to work today because of the unions.”

The hardest part of this work is undoubtedly the hours. When he was working on the first season of The Wire, he put in up to 80 hours per week, sometimes 18 hours per day. “We’d finish at four in the morning on Saturday and then we had to be back at work at 6 a.m. on Monday,” he says. Sometimes the job could get tedious because of the hurry-up-and-wait aspect, which meant a lot of downtime. “If you work 14 hours, you spend around 9 hours standing around and waiting,” he says.

But it all ultimately creates what he describes as “magic on the sets,” when directors and actors use those props and set dressings as part of the storytelling. As a prop master, he’s able to witness moments that are emotional or uplifting—and that’s just in the process, before the piece is even finished. “The biggest reward is the end result of your work, when you watch the movie or show and you see all the nuances,” he says.

As of the start of 2024, Spore wasn’t working on anything, as much of the film and television industry catches up after the actors’ and writers’ strikes of 2023. He expects things to pick up soon, and dramatically. Content that film studios and streaming services had on hand while productions were on hiatus has mostly been released, so demand for more content is imminent. And that’s good news for everyone in the industry.

“We’re all hoping that because they need so much more content to continue, we’ll be really busy in this year coming up in ’24,” he says.