+ By Christine Fillat + Photos by Rachel Waldron

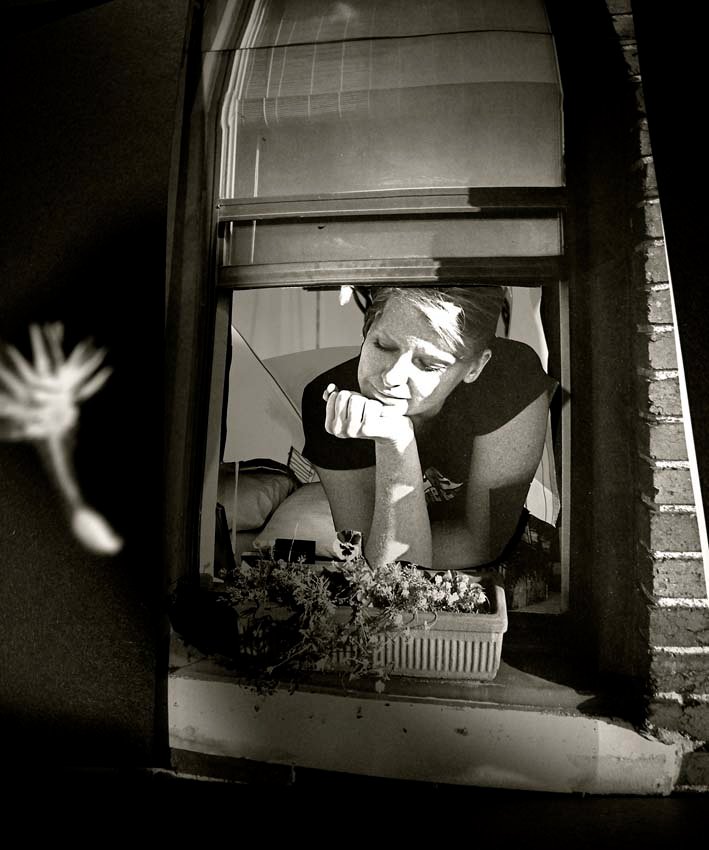

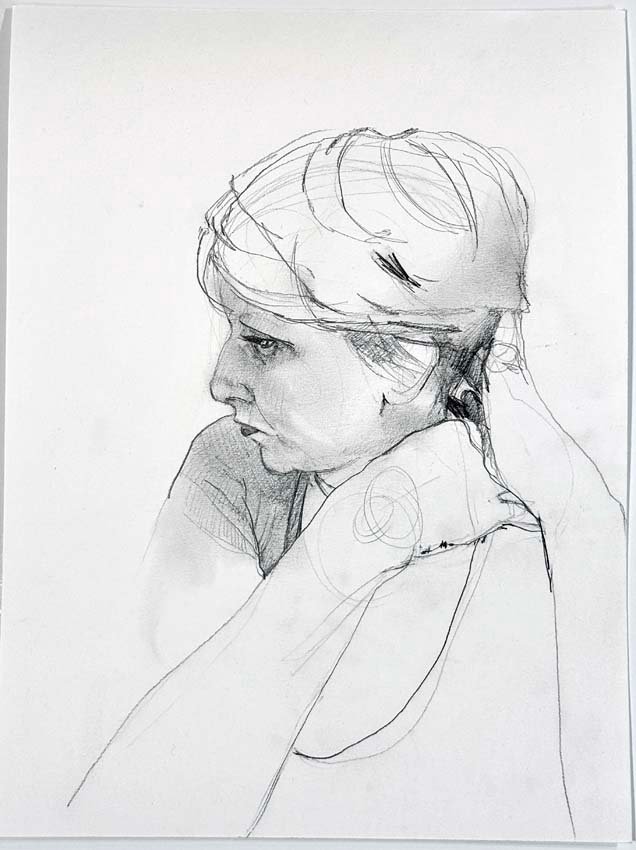

Rachel Waldron is a visual artist with a portfolio of mixed-media art. She is a painter, printmaker, and animator. She is also a museum professional, an exhibits registrar at the Library of Congress. As a youngster, she was a dancer, taking the typical ballet, tap, and jazz classes. “I started in dance before I started in art,” she says. “I love movement and gesture, the ideas of what you can convey. Even just a simple gesture.” She remembers trips with her parents to the Baltimore Museum of Art and was captivated with the art of Henri Rousseau, Vincent van Gogh, and Edward Hopper. In high school and college, she turned to visual arts.

Her desire was to go to art school, but her parents weren’t keen on the idea. They were fine with her signing up for premed at George Washington University, where she only had to take one science course a semester. Her other classes could be anything that she wanted. Such as art. “Luckily for me, that kind of worked,” she says. Thus, along with an education in studio art, Waldron obtained another skill, one that was not on the curriculum: negotiating.

At George Washington University, she studied under Arthur Hall Smith, a classically trained artist, who taught her early Renaissance techniques such as tempera, and she ground her own pigments. “Obviously, that’s not something you do all the time because it’s time-consuming,” she says. She considers herself a traditionalist.

As exhibits registrar with the Library of Congress, which holds around 185 million objects in its collections, her job is to keep track of objects that are on display and those loaned to other museums. She does the shipping and packing, writes the contracts, and sometimes even travels with a piece to its destination.

Her first task at the Library of Congress was to make boxes to house a collection of Tibetan prayer books, the Naxi pictographic manuscripts, which were made by monks in the foothills of the Himalayan mountains. The manuscripts are tiny, with pages made of wood pulp and written in ink made from wood ash. The stories are mainly sorrowful love stories or of postmortem redemption. The books’ edges are singed from candle flame. “It’s just amazing,” she says. “[They] come from the other side of the world, from a language you can’t read, but you can imagine. You can put yourself in that place . . . just by having the opportunity to be that close to that piece, close to that object.” To Waldron, the Library of Congress is an ideal place for a visual artist to work. “You aren’t in the art world, you don’t have this competition, so you aren’t in someone else’s art,” she says. “You’re just in the raw materials. And things from other cultures. It’s pretty cool.” She has worked there for 23 years.

At home, Waldron shares studio space with her husband, Marc Roman (featured in Up.St.Art’s fall 2024 issue). They go to each other for honest feedback. She credits him with helping her break away from the traditional way she had been rendering her art and trying more flexible ideas, using techniques such as collage.

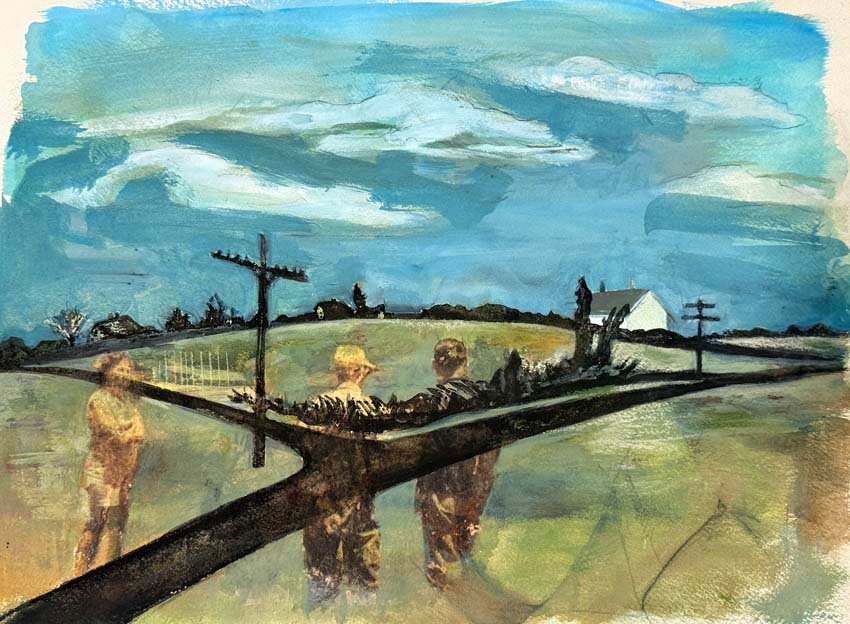

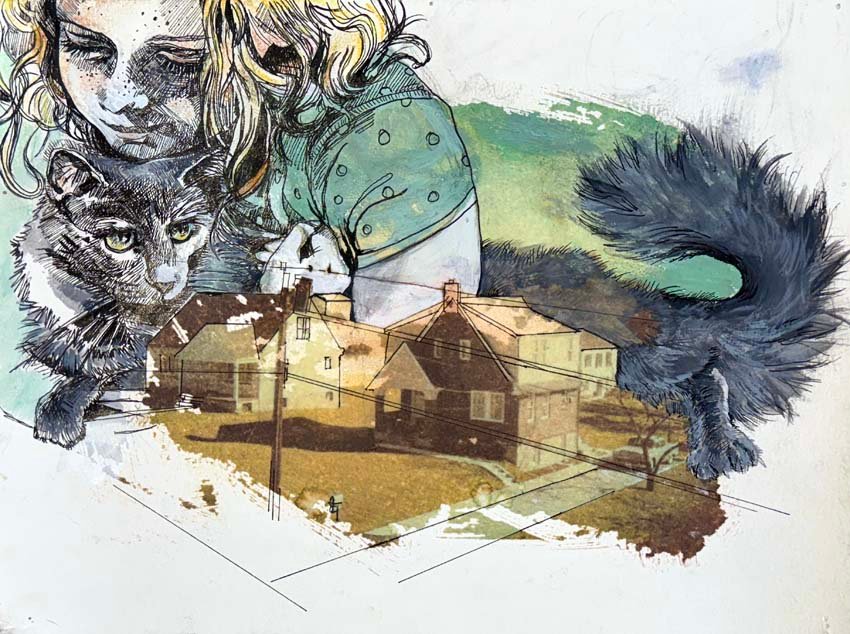

Waldron’s grandfather was an avid photographer. His pictures were regular family snapshots—unposed, random images depicting everyday life. She remembers slide shows with family and the sharing of stories of family lore. Waldron inherited reels of her grandfather’s slides, some of which she has since digitized, preserved, and shared with family members. In the collection, she discovered a treasure trove of images from a pivotal point in her family’s life.

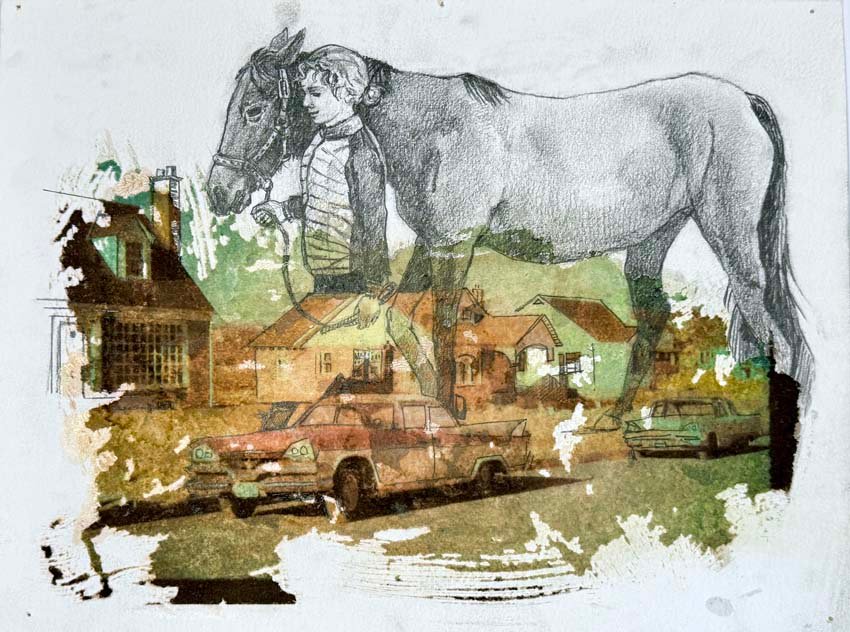

In the late 1950s, much of the family farm was taken over by the State of Maryland to make way for the Baltimore Beltway. The state auctioned off houses that were in the line of construction—fully built homes that were going to be bulldozed. The family purchased some of them. They picked up the houses from their foundations and moved them, creating their own neighborhood on what was left of the farmland.

Her grandfather documented the house-moving operation. There are photographs of lovely two-story houses on the backs of tank movers being relocated to their new foundations. The farm was gone, but their homegrown community took its place.

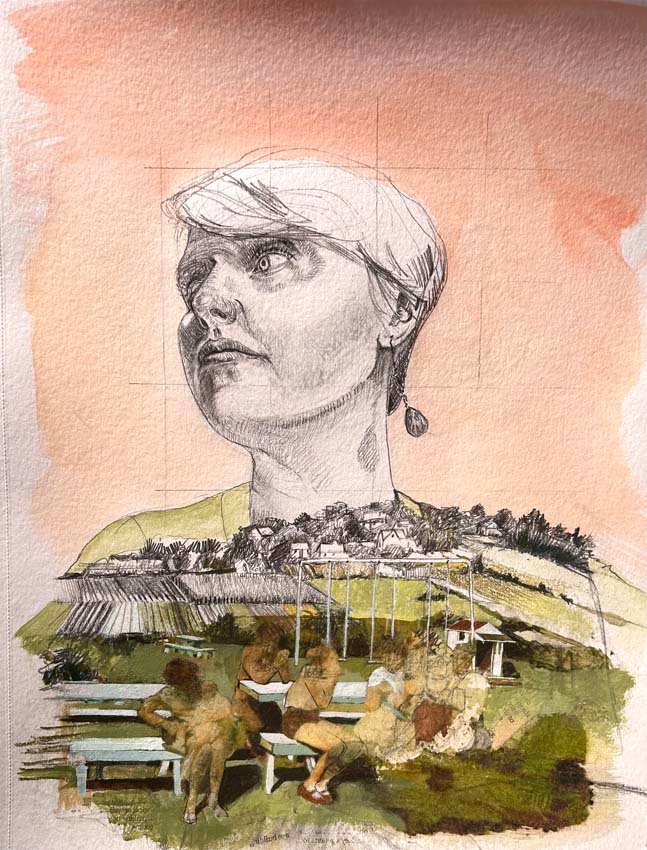

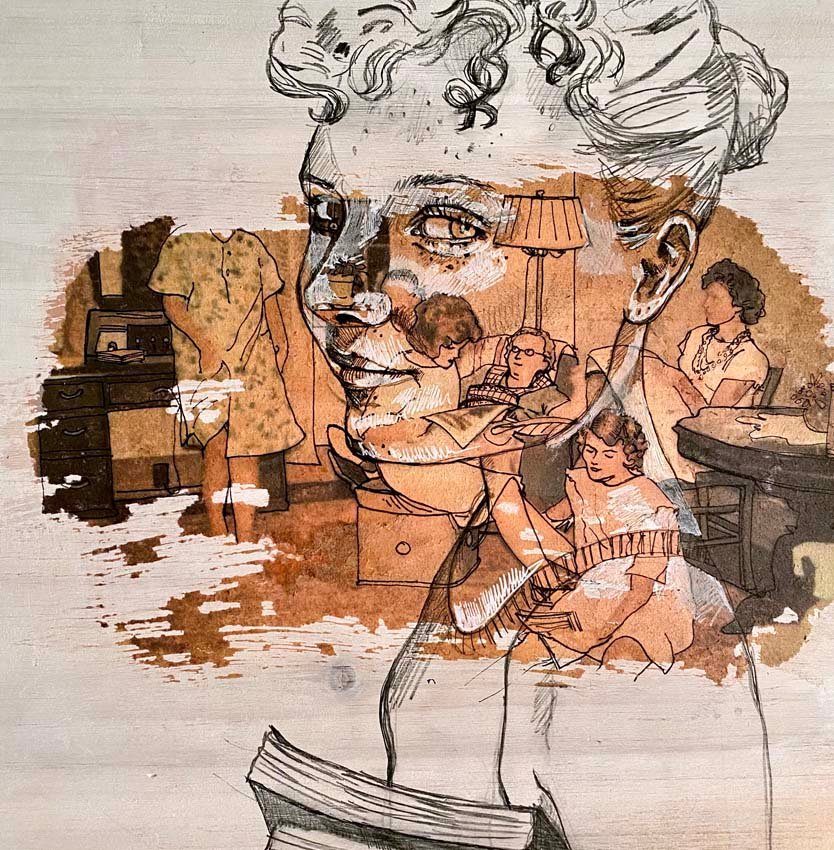

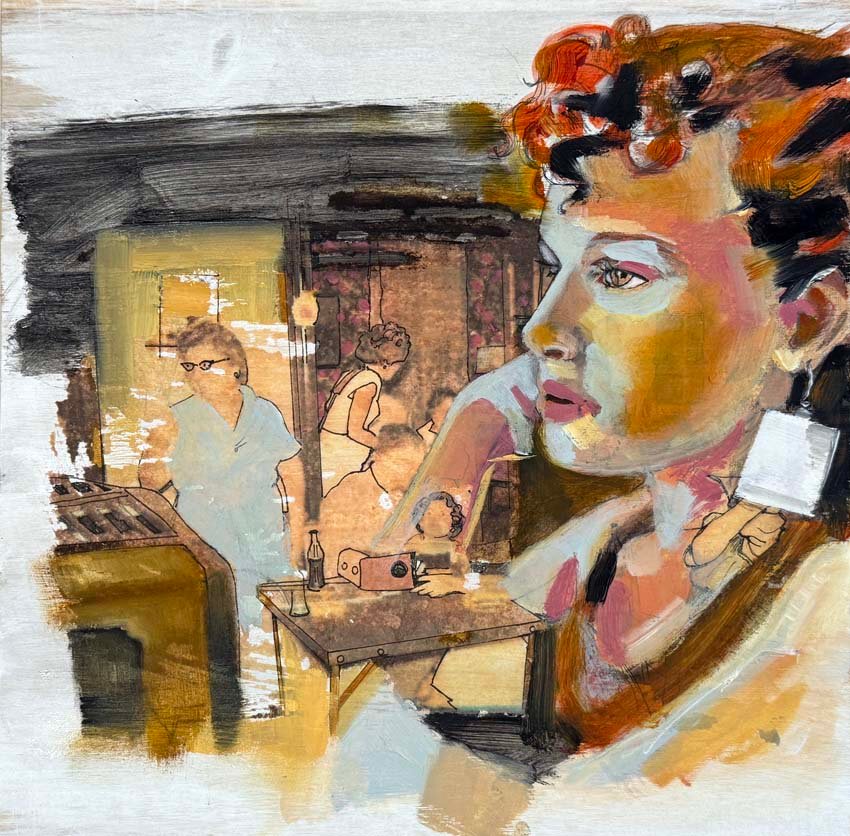

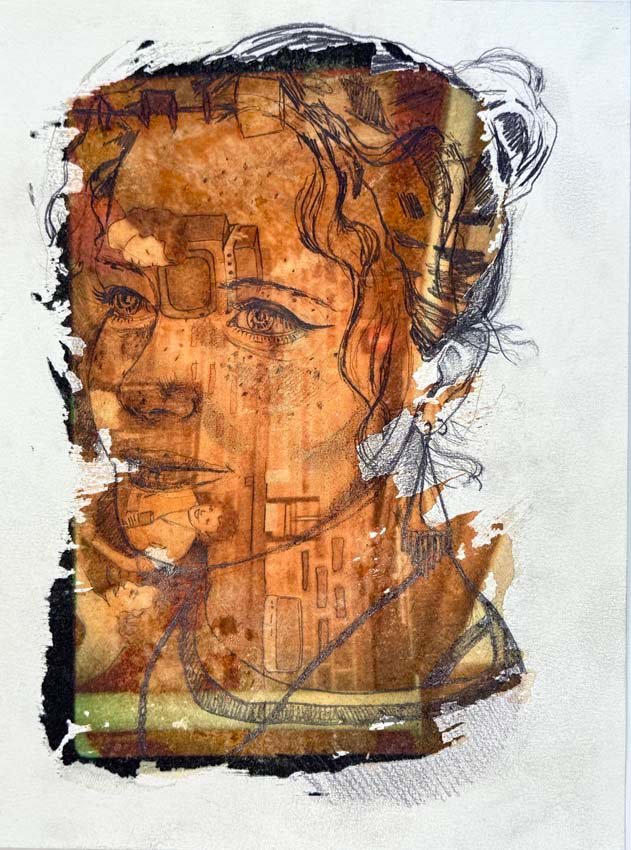

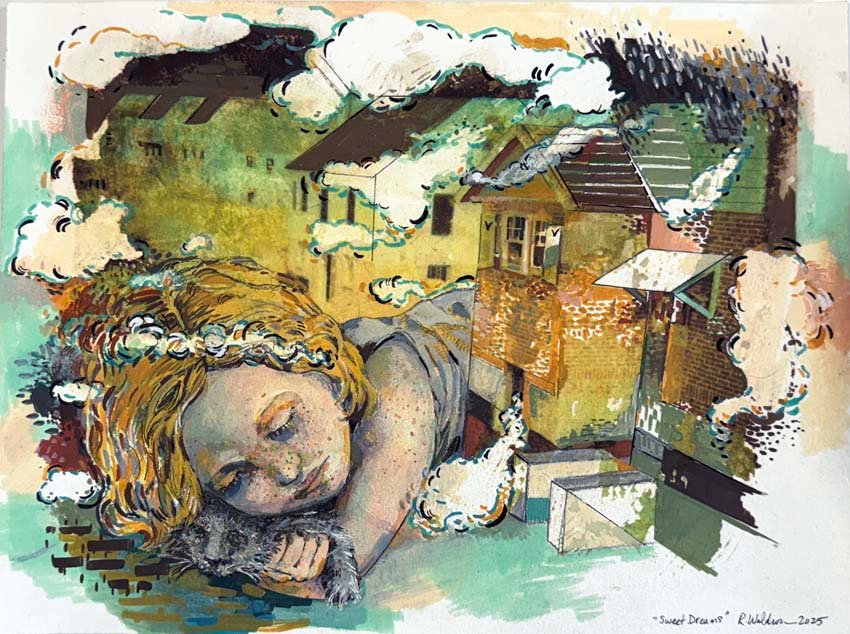

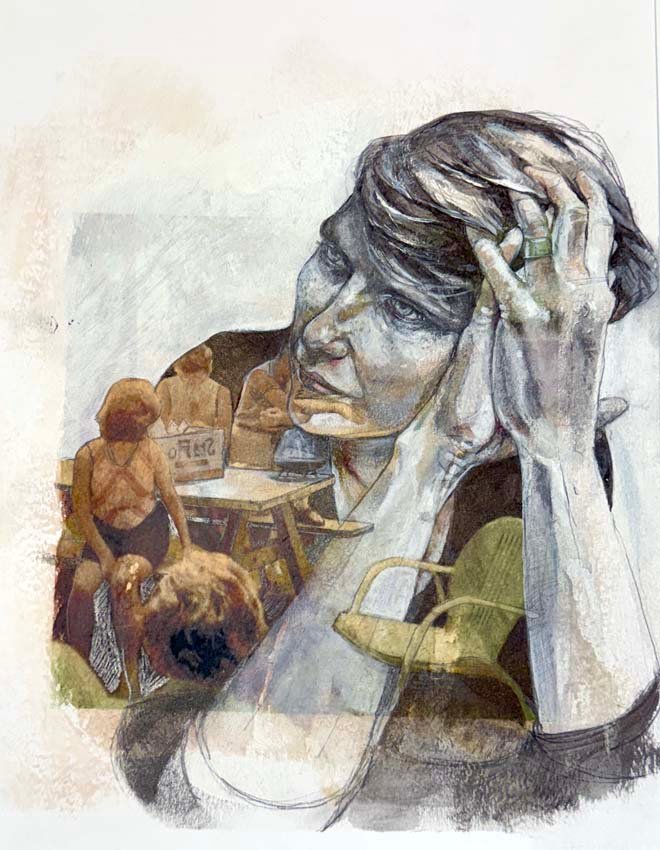

Waldron’s current body of work includes multimedia images involving photo transfer. She starts with a vintage photograph from her grandfather’s collection and transfers it onto paper or wood. The transferred images are hazy, and some parts of the image don’t transfer. This is the challenge and beauty of the technique. Waldron draws on top of the image, typically self-portraits or drawings of her daughter. Then she adds color with acrylic, watercolor, or oil paint. Sometimes, she runs the image transfer vertically and then draws on top of it laterally. Perhaps one can infer the combination of images as memories or thoughts. “It’s like this vision into the past,” she explains.

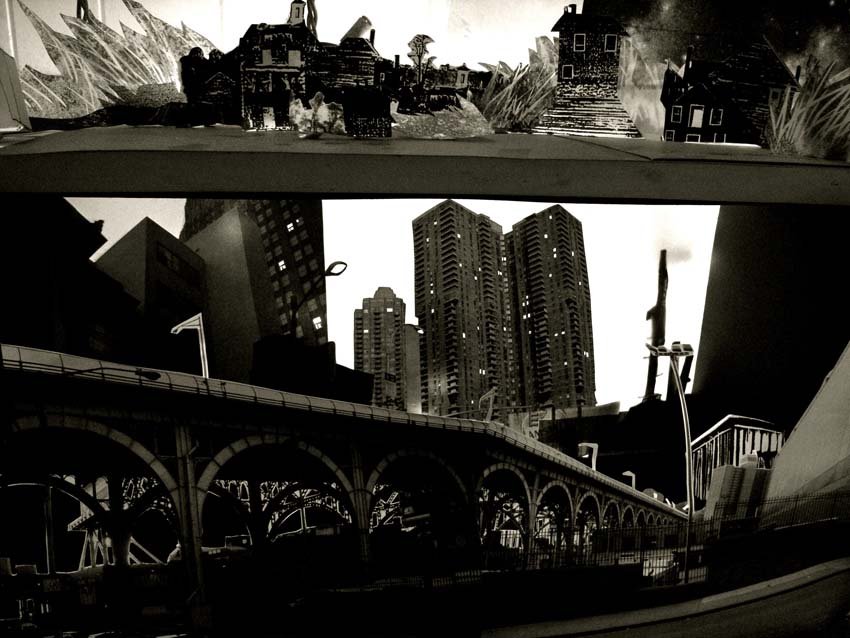

Fate is an animation that Waldron made from stills. Running a little over three minutes in length, it is an amusing story in black and white about cities, moving from place to place, and a chance encounter. The images are cutouts of her photographs, placed in a diorama-like scene, a maquette, of an urban environment with tall buildings, highways, and automobiles. It is a playful self-portrait of modern life and fate, hence the title. “Suddenly, you bring the camera angle down, and it becomes real,” she says. “It’s not just cut paper; it’s a world. I just totally love, love it. It blew my mind when I saw that happen. I was like, this is magc. I need to do this. I need to figure out how to get in there.”

Homestead has the feeling of an old home movie. Images are projected onto different random surfaces in a house: in a hallway, on the backsplash of a kitchen range, on a wall in a bathroom. The images are all from the 1960s and 1970s and have the familiarity of a shared history for anyone who lived during that time: vintage cars, families at parks, beach scenes, people dancing at a party, someone posing in a Communion dress. Trippy music plays in the film, along with birdsong and the clatter of a movie projector. The music is catchy; it is an original track with Waldron on vocals, her husband on guitar, and musican friends Dave Jung on bass and Adrienne Penebre on drums.

She is considering just how to add more elements to the artwork. “I want to see if I can, with the storytelling, open up the page, and the photo just becomes a smaller part of it, in one corner, in one area. That allows my imagination or my vision to take over a bigger portion of the page and add more to it,” she says. “I haven’t figured out how that’s supposed to look, yet. Can I take it to the next level, where it’s not just paper or wood anymore? Do I add fabric? Do I add other elements? How do you get that stuff that’s in your head out so other people can see it? I find it magic. I find it totally magic.”