+ by Julia Gibb + photography by Marie Machin

Neil Harpe’s home in downtown Annapolis serves as a fitting metaphor for the multifaceted artist. From the outside it is charming and unassuming, its front porch painted with touches of soft tropical color, subtly hinting at the creativity contained inside. Harpe resides there with his wife, Alexandra Fotos, and their two small dogs, Dino and Yianni. The couple’s home serves as a living space, gallery, printmaking and painting studio, and, until recently, a workspace for Harpe’s business repairing and restoring vintage Stella guitars. Enter, and an ever-evolving display of paintings rendered in watercolor and acrylic paints, along with prints created with several printmaking methods, greets you. In the next room, you’ll find more art, books, and a printing press. Around the corner: an office with flat files full of artwork. For decades, Harpe has participated in solo and group exhibits, locally and internationally. Still, what the artist’s home reveals is only a glimpse of the massive body of work and vast experience behind this native Annapolitan’s long career in the arts.

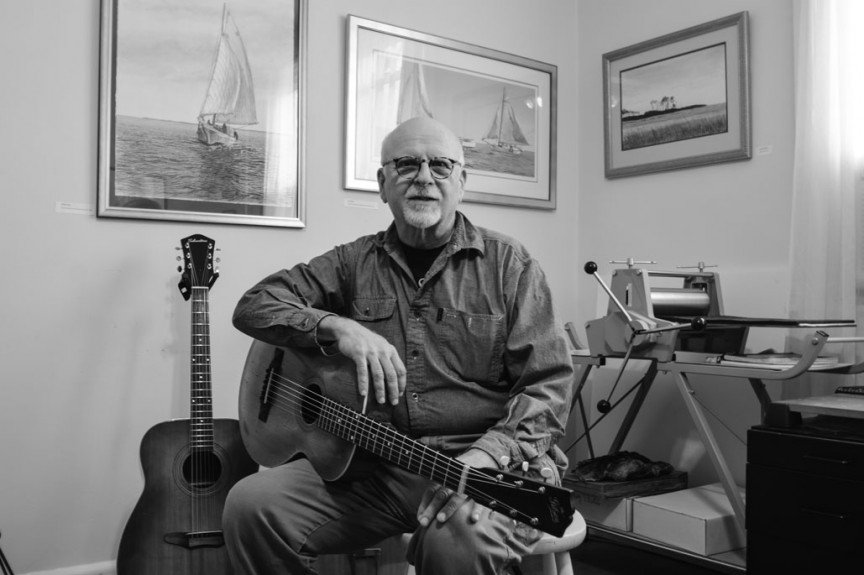

With characteristic humility, Harpe explains that he enjoyed drawing as a youngster but didn’t think of himself as a visual artist. “I could draw, but what’s so unusual about that?” he says. Instead, he focused on music, starting guitar lessons when he was in fifth grade. In his teen years, he jammed with the town beatniks and St. John’s College students. These older friends frequently traveled to the southern United States to collect hard-to-come-by blues records. Among them was folk musicologist Tom Hoskins, who returned from one such trip with blues legend Mississippi John Hurt. Having access to such authentic resources instilled in Harpe a lifelong love of blues music, and he has been performing blues on guitar and vocals ever since. He cut several CDs, both solo and collaborative, created a series of portraits of famous blues artists, and provided illustrations for Ted Gioia’s Delta Blues, a nonfiction book about America’s blues masters. In 2005, Harpe authored The Stella Guitar Book, an informative volume about the instrument so integral to the history of early American blues.

With characteristic humility, Harpe explains that he enjoyed drawing as a youngster but didn’t think of himself as a visual artist. “I could draw, but what’s so unusual about that?” he says. Instead, he focused on music, starting guitar lessons when he was in fifth grade. In his teen years, he jammed with the town beatniks and St. John’s College students. These older friends frequently traveled to the southern United States to collect hard-to-come-by blues records. Among them was folk musicologist Tom Hoskins, who returned from one such trip with blues legend Mississippi John Hurt. Having access to such authentic resources instilled in Harpe a lifelong love of blues music, and he has been performing blues on guitar and vocals ever since. He cut several CDs, both solo and collaborative, created a series of portraits of famous blues artists, and provided illustrations for Ted Gioia’s Delta Blues, a nonfiction book about America’s blues masters. In 2005, Harpe authored The Stella Guitar Book, an informative volume about the instrument so integral to the history of early American blues.

It wasn’t until Harpe found his circuitous way to the Corcoran School of Art in 1965 that he became serious about being a visual artist. He had spent a year at American University, but couldn’t resist the lure of downtown galleries such as the National Gallery of Art and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Upon transferring to the Corcoran, he found himself in the middle of what is likely the most important visual art movement ever to spring from the District of Columbia: the Washington Color School. In reaction to New York City’s energetically gestural abstract expressionist movement, the artists of the Washington Color School created orderly abstract compositions through the use of color theory—hard-edged geometric shapes, stripes, or circles, often rendered in bright acrylic paint colors. The Corcoran was a hotbed of key figures in the movement, and being a student at that time “was a little intimidating, because there was so much going on, and you’re just this little thing down here,” he says. But Harpe thrived in the highly stimulating environment. As a student, he enjoyed full access to the Corcoran Gallery, two Corcoran Biennial Exhibitions, and his instructors, including artists Alexander Russo, Thomas Downing, and Ed McGowin.

After earning a four-year diploma at the Corcoran and his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, Harpe went on to earn a Master of Fine Arts degree at George Washington University (GW). There, he continued sharpening his etching skills, but his appetite to learn lithography had been whetted during his time at MICA. Because GW did not offer lithography classes, Harpe attended University of Maryland as a visiting graduate student, where he studied with master lithographer Tadeusz Lapinski. After graduating, Harpe taught college art classes for seven years, first at the Corcoran, then at Northern Virginia Community College and University of Maryland University College.

After earning a four-year diploma at the Corcoran and his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, Harpe went on to earn a Master of Fine Arts degree at George Washington University (GW). There, he continued sharpening his etching skills, but his appetite to learn lithography had been whetted during his time at MICA. Because GW did not offer lithography classes, Harpe attended University of Maryland as a visiting graduate student, where he studied with master lithographer Tadeusz Lapinski. After graduating, Harpe taught college art classes for seven years, first at the Corcoran, then at Northern Virginia Community College and University of Maryland University College.

Among the many mediums Harpe has mastered is Mylar® lithography, which he studied in depth at Atelier North Star in Burlington, Vermont, with artist Mel Hunter, author of The New Lithography. In traditional lithography, the artist draws directly on stone, which is then chemically treated, inked, and used to make prints on paper. Mylar® offers the advantage of transparency: the artist draws on the film, able to achieve accurate registration of many layers of colors. The transparencies are used to create aluminum plates, from which prints can be created. This technique gave Harpe the freedom to create colorful representations of people, musical instruments, and workboats of the Chesapeake Bay.

In the 1980s, Harpe discovered local painter Dick Harryman’s downtown Annapolis studio and Chesapeake Bay-themed artwork. Harpe recognized the commercial potential of the subject matter and made sizeable series of Mylar® lithographs depicting watermen and boats in action. Researching these subjects firsthand, Harpe took early morning trips to the Eastern Shore. “I had to get up in the morning at two, and after a couple cups of coffee, grab my cameras and away I’d go,” he recalls. Harpe eventually got used to the routine, and still mines the several hundred photographs he took for source material. “These photographs ought to be shown,” he says. “One picture I took out on the Choptank River [shows] in one frame about twenty skipjacks. There aren’t even that many skipjacks afloat today.”

In the 1980s, Harpe discovered local painter Dick Harryman’s downtown Annapolis studio and Chesapeake Bay-themed artwork. Harpe recognized the commercial potential of the subject matter and made sizeable series of Mylar® lithographs depicting watermen and boats in action. Researching these subjects firsthand, Harpe took early morning trips to the Eastern Shore. “I had to get up in the morning at two, and after a couple cups of coffee, grab my cameras and away I’d go,” he recalls. Harpe eventually got used to the routine, and still mines the several hundred photographs he took for source material. “These photographs ought to be shown,” he says. “One picture I took out on the Choptank River [shows] in one frame about twenty skipjacks. There aren’t even that many skipjacks afloat today.”

As a representational painter, Harpe is mostly self-taught, as the bulk of his instruction at the Corcoran was in abstract painting. He has developed his own vocabulary with acrylics. Once he becomes interested in a subject, he will stick with it for a long time—he painted compositions that included a bit of beach, ocean waves, and sky for an entire year. Recently, though, he has returned to his Corcoran training, painting abstract compositions in the Washington Color School style. He cuts Gator board (rigid foam board with wood fiber veneer) into geometric shapes, wet mounts canvas onto them with archival glue, and paints vibrant stripes in carefully deliberated patterns and colors using masking techniques. Some of this work exhibited in January at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts, where he now teaches etching. He feels both challenged and liberated by the practice of painting without having to choose subject matter and other intricacies of working representationally. “You feel like you’ve been set free from all [those] things,” he reflects, “and you can just do art.” █