+ By MacDuff Perkins

As a young person growing up on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, artist Jonathan James struggled to find a welcome acceptance among friends and family. “All around me, I’d hear people talking about their lives in a way that ran counter to what I wanted,” says James. “I had to reimagine a world for me, a world that I wanted to be part of.”

And so James’ imagination began to grow and develop extraordinarily. But imagination is not sustainable in a vacuum; it longs to communicate, demands expression. But without the tools necessary to communicate, James was stifled. It wasn’t until a chance meeting with a drawing instructor that James found a way to convey their thoughts and feelings about the world. “I was looking for a level of communication I didn’t have the skills for at the time,” they say. “Developing a visual style meant developing my own self and personality.”

Once skills were acquired, creative expression began to flow at a breakneck speed. And while James was still the person who didn’t necessarily “fit in,” their talent was a door to acceptance. Art instructors were encouraging, and James’ first paid drawing job involved working with their father, a civil engineer, to develop topographical maps used by Anne Arundel Community County.

While mapping out landscapes was great for the teen, James needed much more. Enrolling in a drawing class at Anne Arundel College, James met their first mentor, Donna Hepner, in an entry-level class. “Donna exploded my head to what was possible in the world,” says James. “This was an answer to what I initially recognized as a limitation. Donna taught me that if I saw a limitation, I had to demand more from my experiences. Nobody is going to give you more; you have to seek it for yourself.”

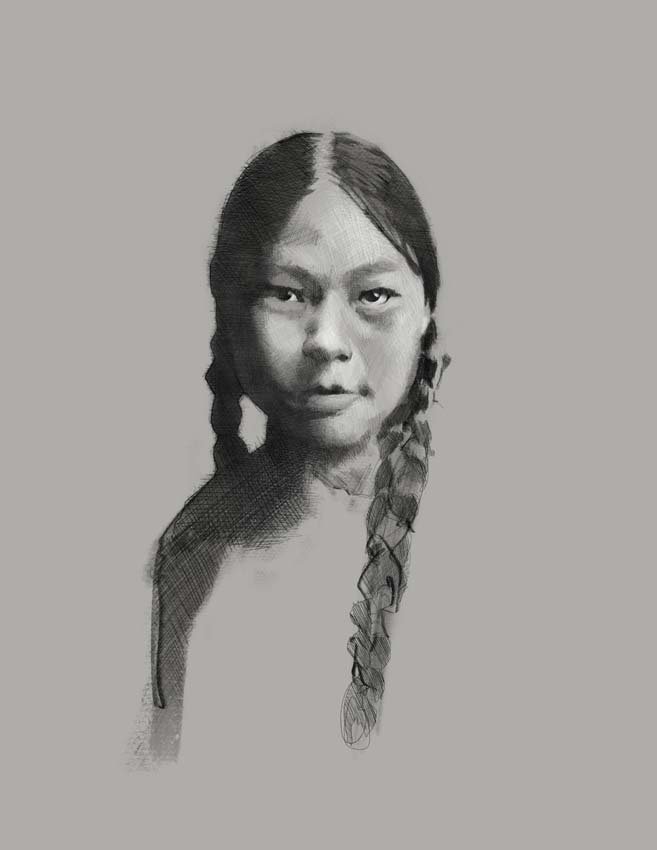

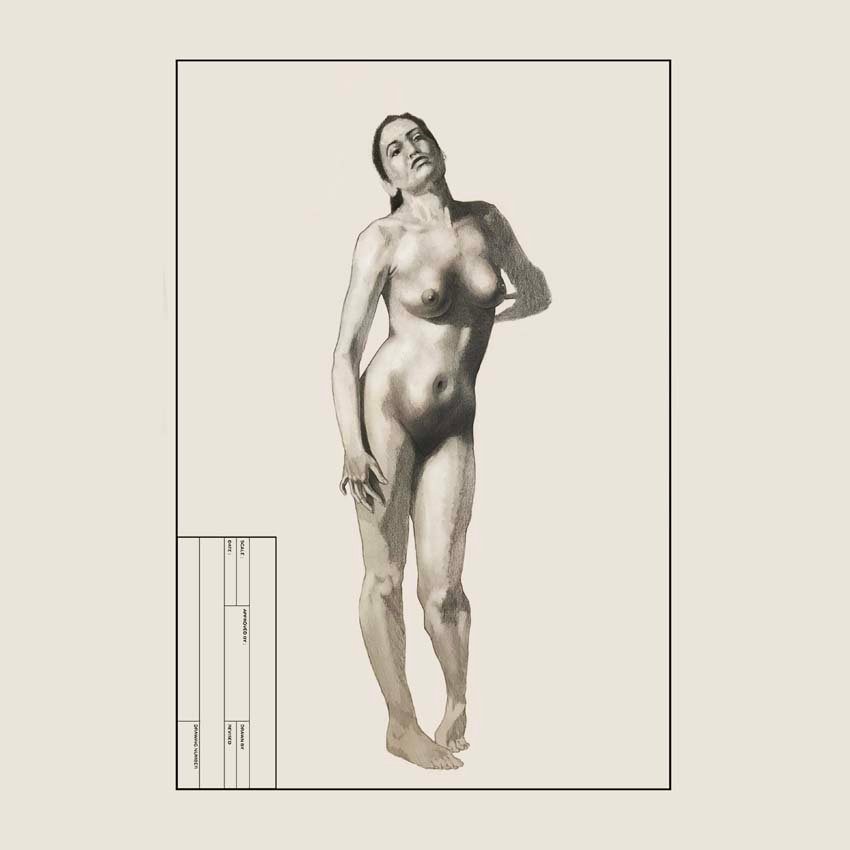

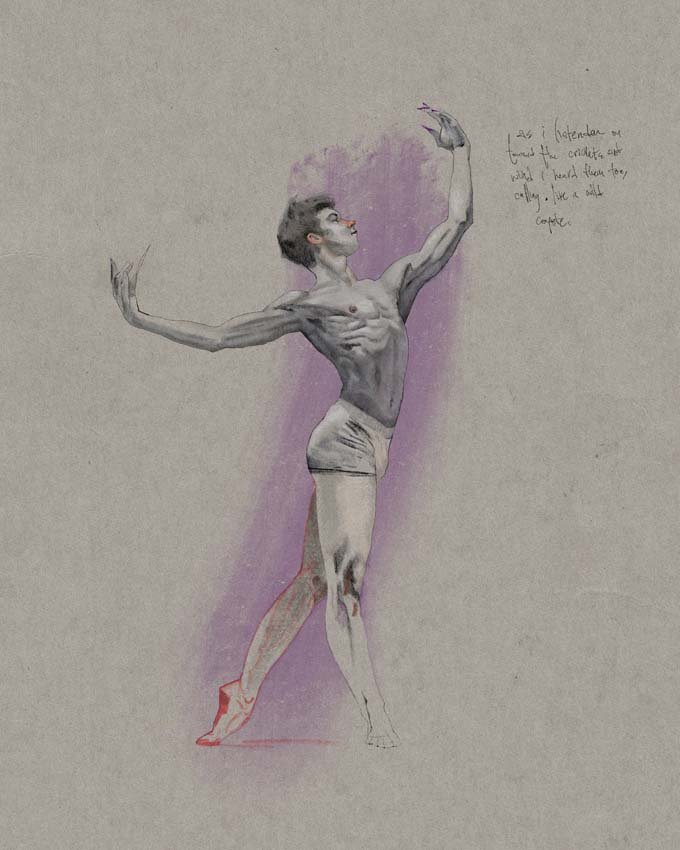

This took James across the country, to the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, where they began to study fine arts, focusing on the rigid demands of realism and accuracy. Oil painting allowed James to challenge their comfort zone while developing a methodical process and respect for the medium. “With oils, there’s a way you have to do it,” says James. “There are rules, and a method, and I respect that. Once you understand the structure of those rules, though, you can bend them ever so slightly to re-create the process.”

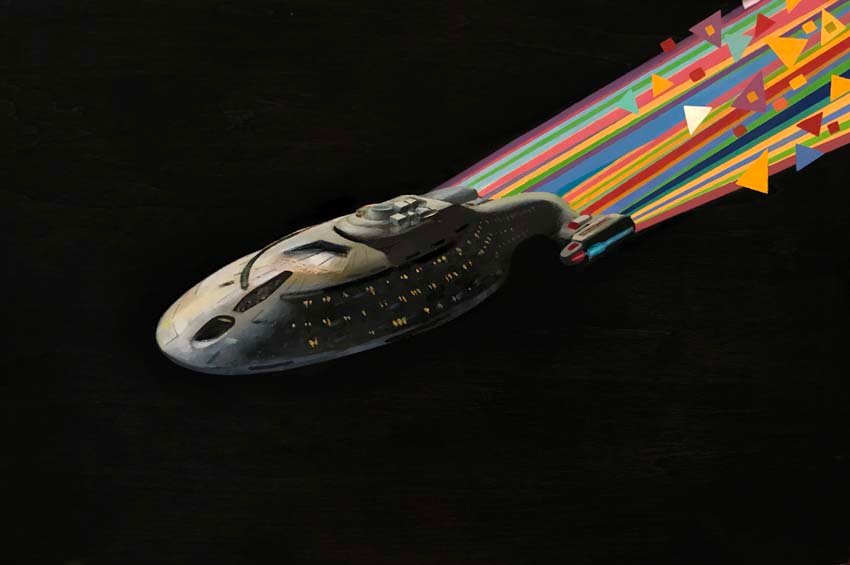

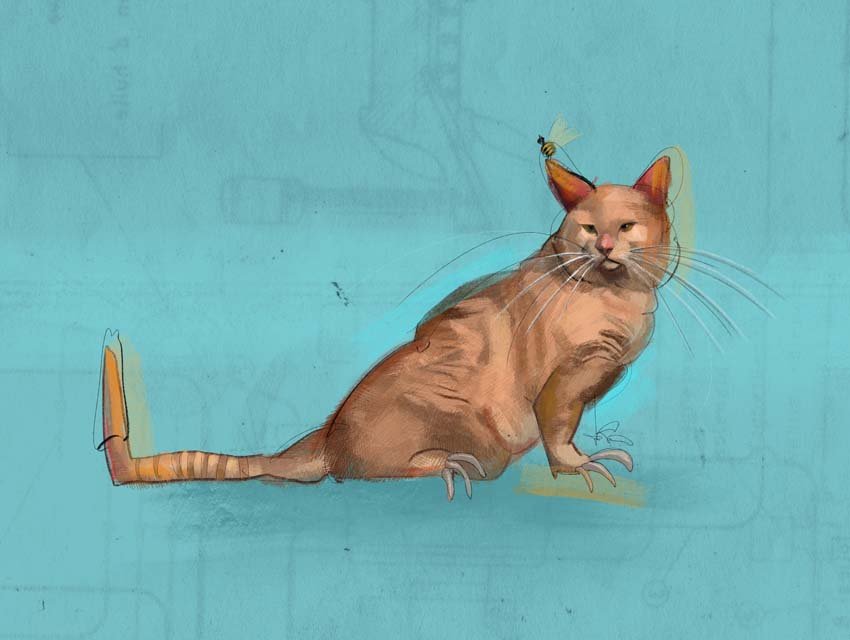

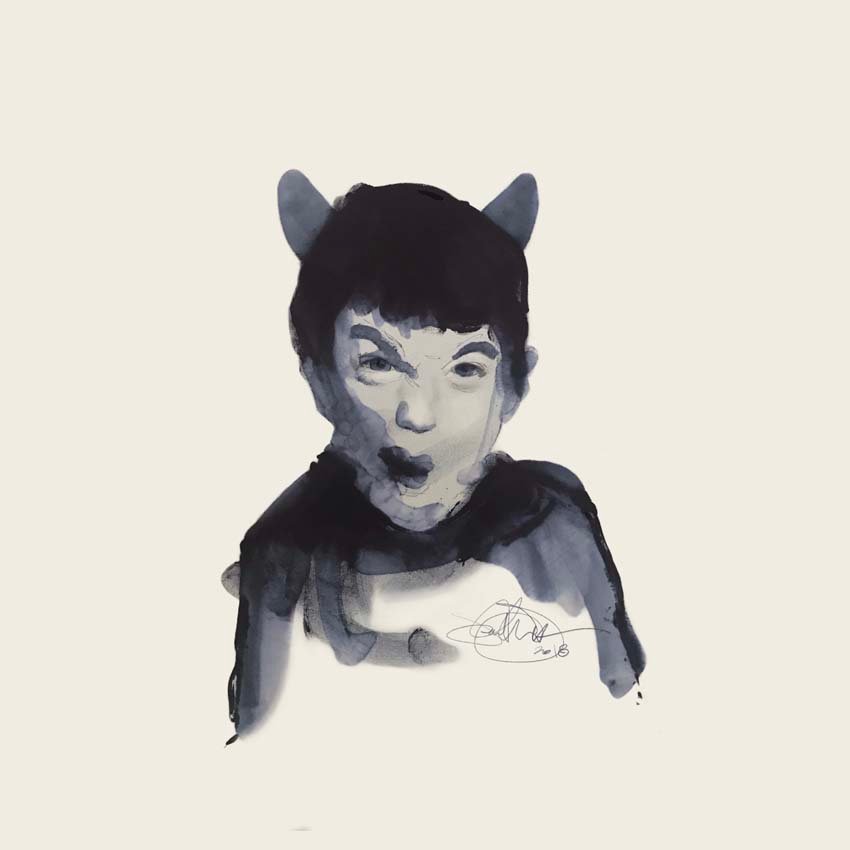

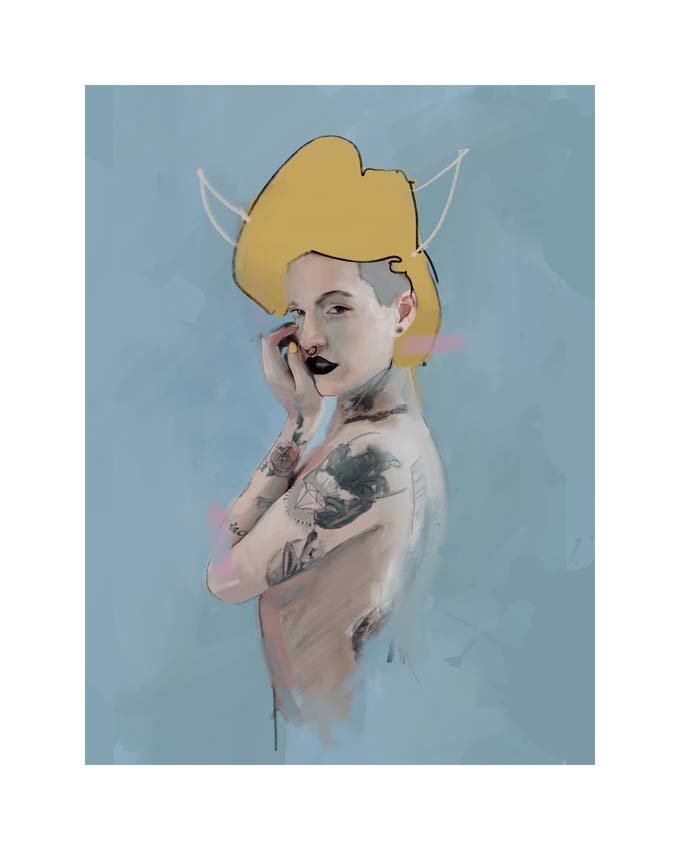

This re-creation does not simply evolve the color and texture of James’ prints. There comes a small warping of reality, moving the object just outside of the realm of recognition—an adorable puppy dog with a raptor’s claws; a child with antlers holding a bumblebee; Charles Darwin with teddy bear ears; Lizzo as a mermaid. James’ muses all seem on the verge of a revelation or a primal scream.

James’ boundary-pushing brought them back to the East Coast, where they continued studying fine art at Towson University—drawing, painting, and printmaking, with a heavy dose of graphic design to help with commercial success. But then drugs entered the scene, putting a massive halt to the progression of James’ art career. “Drugs deteriorated my life for a bit,” they say. But by embracing experience as a gateway for connection, James rebounded with greater strength and commitment. “I can imagine my life as a period of three rebirths. And getting off drugs was the second one.”

This revival brought forth new eyes and introduced a hyperreality to James’ art. “I came to a point where I want to make things as accurately as possible,” they say. “I had to relearn how to draw shadows and light.”

As James continued with the reeducation process, they found that creation was the tool that drug use was trying to provide. By expressing perception emotionally, James allowed for a release of the pain and trauma they had been carrying around for a lifetime. “I just want to make things and create,” they say. “I’ll try to do that in whatever way, knowing that I’m circumnavigating my own depression.”

James was able to dilute and dissect the reality of their experiences with the control of a trained artist, allowing for insight and healing. And as James began to develop commercial success, they had the tools for working with those who might still be struggling with creative expression.

“With graphic design, I’m constantly questioning how best to communicate someone else’s thoughts,” says James. “It takes a great deal of empathy, of understanding that individual. I can’t be too biased. I have to stand outside myself to create someone else’s vision. But I don’t like to take on other people’s emotional baggage. A lot of people have a hard time communicating. I feel I’m pretty good at helping people communicate what they’re looking for.”

This aptitude for collaboration has led to professional projects with significant partners. “Oh man,” says James. “I have so many cool projects that I get to work on, but they have NDAs [nondisclosure agreements] and I can’t share the work.”

Working in different styles with creative teams presents a challenge, and excelling in the project leads to validation. “One of the biggest validating rewards is when I get a team of creatives and show them what I can create,” says James. It’s a process of deep listening, of understanding the structural demands of a corporation, and then bending the rules just a tad to supersede expectations. “Just because someone gives you a solution doesn’t mean it’s the right solution,” says James. “You have to allow yourself to be patient with people and their ideas, but I also know that I trust myself and that I know how to solve this issue.”

To be a fringe artist working within corporate confines is a coup, to say the least. But to break apart the wants and needs behind a logo—a graphic—and turn that into an enticing piece of art with a message is what James wants to do. The slight refraction of cultural norms allows James to create a world of blemished perfection, where all are welcome. James is a tinkerer, picking apart their objects to find the hidden soul.

“I obsessively watch process videos on YouTube,” says James. “The idea is to show my object in a way that’s not presumptive, expressing a thorough or well-conceived thought. I’m not telling a story; instead, I’m creating the tools to tell the story.”

These tools assemble quickly. Working frenetically (often on the bedroom floor), James will swiftly sketch and paint a subject before reworking it over and over again, pulling the piece to the place where it’s supposed to be.

“If I try to give someone an idea, it’s still biased,” says James. “My perception is not the perception. I simply get the opportunity.” And perceptions are always flawed. Memories are like snowflakes—never the same despite their rampant similarities.

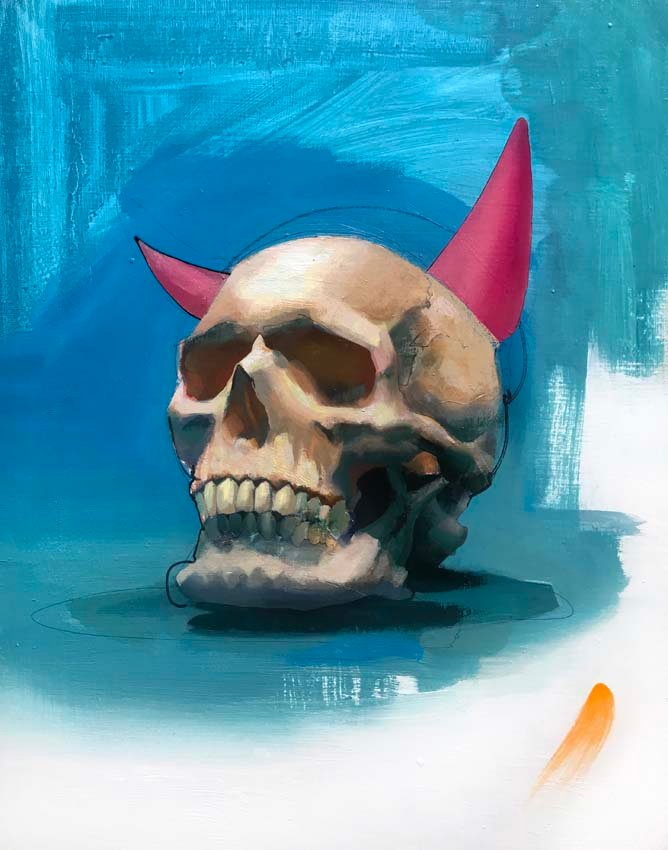

“Donna Hepner said that every picture should have a joker,” says James. “Something that undermines it.” For example, a deer skull rests on an intoxicating field of lapis lazuli blue. James’ talent for shadows creates a quiet space to contemplate the distinction between comfort and fear, decay and enlightenment. The harsh form of the skull and antlers presses against the deep azure. The painting is unsettling in its familiarity. But then, there’s an orange dot in the right corner, leaving the viewer to question whether it is perhaps a mistake or a smudge—that’s the joker.

“The dot is a usurper,” says James. “The dot makes sure you don’t have a perfect understanding of a thing. The dot doesn’t belong, but it has to be considered part of it. It’s disruptive, but it also balances everything. When I was painting it, I thought to myself, ‘Look at this lovely blue painting. Here we go: orange dot. Now it’s done.’”

James’ joker puts reality on the verge of anarchy. It is an invitation to break apart the confines of perspective and allow for an entire restructuring of discernment. The joker is the calling card for the revolution of the mind. █

For more information, visit jonathanmjames.com or follow Jonathan James on Instagram @jonathanmjames.