+ By Julia Gibb + Photos by Alison Harbaugh

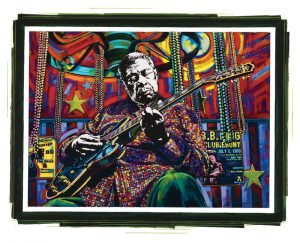

The face of Mississippi blues legend Terry Evans, rendered in high-contrast black and white, peers pensively out of the interior darkness of a red and turquoise train car, where he sits, holding a guitar in his lap. Framed in triangles by telephone poles and electrical wires, the sky blazes in painterly blue, green, and purple abstractions. The road and the gravel beside the tracks sizzle in gold and purple. This piece is part of H.C. Porter’s latest body of work and multimedia exhibit, Blues @ Home: Mississippi’s Living Blues Legends. With 31 mixed-media portraits, Porter has captured a snapshot of contemporary Mississippi blues culture, encompassing subjects young and old, black and white, and from all walks of life. Nine of the artists have since passed but were alive and influential while Porter was creating her works. She traveled around Mississippi with Lauchlin Fields, who helped collect the oral histories that would become part of Porter’s interactive exhibit and are included in its accompanying book.

Photographer & Painter, H.C. Porter in her Annapolis home studio. Behind her is a screen print of her photograph ” Waiting on the Parade “

from her Backyards & Beyond Series that will soon be transformed into a colorful painting.

Photos by Alison Harbaugh

“If you say, ‘I’m from Mississippi,’ it either starts a conversation or ends a conversation,” Porter says, laughing. Born and raised in Jackson, the artist is familiar with the stereotypes and preconceived notions that Mississippians face. For decades, her work has represented the diversity of Mississippi culture and its residents, including the Midtown neighborhood of Jackson, Hurricane Katrina survivors along the Mississippi coastline, and living Mississippian blues legends. Her works of social realism depict the diversity and universality of the human experience. Porter currently works out of her loft studio in the Annapolis home that she shares with her partner, Mollie MacKenzie, and MacKenzie’s daughter, Samantha.

As a young artist, Porter inherited her mother’s painting talent and then her Olympus camera. She quickly fell in love with the darkroom and has had one of her own since she was 16. After majoring in painting and photography in college and then honing her printing skills, working as art director and master printer for sports artist Rick Rush in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Porter turned her attention toward combining her technical expertise into what has become her unique style of storytelling.

Porter’s formative relationship with the Mississippi blues began during her college years. She would attend the Subway Lounge, an after-hours blues club, in Jackson. Located under the Summers Hotel, it was an established stopping place for black travelers during the segregation era. Her parents worried, as parents will, not because they felt she was mingling with an unsavory crowd but because the building was in danger of collapsing. Drinks were sold out of a house next door to the club. “You would go over and knock, and they’d raise the sash window, and you’d ask for a bucket.” For about five dollars, clubgoers would get six bottles of beer packed into a bucket of ice to take next door.

After earning her bachelor of fine arts at the University of Alabama, Porter returned to Jackson. She began making blues-related art, traveling to blues festivals, and selling six-color serigraphs of what she observed there. Establishing her own studio in 1987, in the Midtown neighborhood of Jackson, she started a grant-funded neighborhood program, Avenue for Art, opening her space to local children so that they could learn about art and experience new ways to express themselves. Inevitably, she turned her camera toward her students, then her students’ families and neighbors. “I became this . . . accessible portrait artist for the neighborhood, and the images started seeping into my work,” says Porter, ” . . . these powerful, questioning, piercing images of these adaptable, spiritual kids.”

Describing her artistic process, Porter explains that “back then, I was doing it the same way Andy Warhol did it, using copy cameras and shooting onto line film.” Starting with a black-and-white photograph, she would do multiple exposures of each image to capture different levels of detail in her compositions. “Then,” she says, “I would hand cut the film and literally Scotch™ tape it all together to get the one big piece of film I wanted.” Her pieces still start with photographs, but now she shoots with a digital camera and prepares her images using computer software. After printing the black-and-white images onto paper, Porter works color into her pieces using acrylic paint and colored pencils.

Porter made the transition to digital photography when Hurricane Katrina devastated the Mississippi coastline in August of 2005. She took her camera on the road, documenting the persistence and the resilience of Mississippians who had lived along the coast for generations. Working with Karole Sessums to collect oral histories, their project mantra was, “There is healing in the telling and the being heard.” Their efforts resulted in a collection of 81 “environmental portraits”—subjects surrounded by wreckage and rebuilding in the year following the natural disaster. Backyards & Beyond: Mississippians and Their Stories has traveled to galleries, art centers, and museums around the nation. Eight original works, along with audio, video, and images of other portraits from the series, are part of the permanent collection at Waveland’s Ground Zero Hurricane Museum.

Blues @ Home: Mississippi’s Living Blues Legends is the result of a dedicated and sometimes difficult journey that began in 2011. Some of the living legends lived under the radar, and she had to communicate indirectly with them through family members or find places based on directions that often had her searching for visual landmarks rather than street names or house numbers. The oral histories collected by Fields became part of the traveling exhibit and are available through handheld audio wands; the stories are also excerpted in the book. Color reproductions of the works are juxtaposed with their black-and-white photographs, serving as both source material and artwork. Porter does her best to bring as many of the musicians featured in the exhibit to her gallery show openings. At the opening for her most recent exhibit, which ran from January to March 2018 at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts, 85-year-old Grammy winner Bobby Rush, Vasti Jackson, and Eden Brent played blues to a sold-out auditorium crowd.

Porter stays connected to her Mississippi roots through her H.C. Porter Gallery, housed in a historic building in Vicksburg. But now she is wondering what Annapolis stories could be narrated through her work. “I’m looking for a project,” she says, “like—‘hey God, what am I supposed to be doing?’ because I don’t know, and it’s driving me crazy.” She hopes to find opportunities to work with local children and other Annapolitans. “When the Maryland Hall show was up, we had several different schools come in. They brought kids of all ages—art students, band students—and that was really fun for me,” she recalls. She interpreted her work and process for them and heard their reactions—how they felt about the individual musicians and their oral histories. “To help [kids in Annapolis] create would be exciting.” █