+ By Ellen Moyers

In the 1980s, Annapolis was on a roll, entering its second golden age since the 1760s, when it was the cultural center of the colonies. The city’s treasured icon, the Maryland Inn, which had stood at the top of Main Street since it was built as a home and house of entertainment by civic leader Thomas Hyde in 1772, had been fully restored to its previous glory. It boasted an exciting jazz club in its downstairs that featured the nation’s great jazz artists, including Dave Brubeck, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Monty Alexander, Teddy Wilson, Ethel Ennis, John Pizzarelli, and Charlie Byrd. Meanwhile, popovers and caviar were favorite staples in the Inn’s elegant, first-class restaurant, the Treaty of Paris. Legislators and town leaders often chimed, “Meet me at the Inn,” gather in its intimate but busy bar. It came to symbolize a new vitality that spurred economic benefits for the whole city, which came alive with music venues, festivals, and good times up and down Main Street and toward Eastport.

The seed of this renaissance was planted in 1965, when preservationist Anne St. Clair Wright and then Mayor Roger “Pip” Moyer sparked hometown pride and led the city’s residents to vote for downtown Annapolis to be designated a National Historic Landmark. But the boom times were driven by the work of a visionary entrepreneur with a passion for preservation and jazz and who made his work into art with an elegant style. Fifty years ago, Paul Pearson, a former farmer, restored five historic inns and built three new condominium developments in blue-collar Eastport on Spa Creek, transforming the city.

Born in 1925 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, to a Quaker family that had a history of transforming generations around them, Pearson was named for his grandfather, purportedly a teacher at Swarthmore College and a founder of Chautauqua, the educational, social, and entertainment movement of the 1800s. His uncle, syndicated columnist Drew Pearson, wrote the popular Washington Merry-Go-Round.

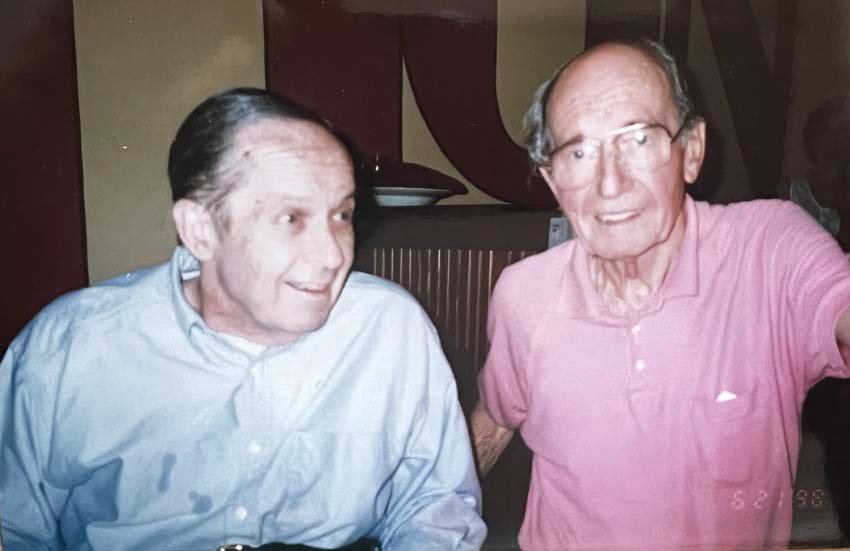

Energetic from an early age, Pearson played soccer on the Exeter High School and Harvard University teams. He was an accomplished sailor, learning the craft in Kittery, Maine, where, at age eight, he and his brother built a sailboat. Graduating from Harvard with a degree in the economics of agriculture, he managed his uncle’s Montgomery County sod farm until securing 1,800 acres of his own to raise sod. Always an innovator, he won conservation awards for using contour and no-till planting methods. He was as comfortable on a tractor as he would be managing the Inn.

In his early adult life, Pearson served in the navy aboard the USS Washington. After World War II, he stayed in Paris with his father, who took a job as bureau chief for NBC. There, he met and married Nicole Hargrove, a dancer. Moving back to the states, they settled in New York City; Pearson became a writer for the Tex and Jinx radio show—the Today Show of its day—and his wife danced with the famed Agnes de Mille. Over time, Pearson missed the stability of the land he loved. When his uncle offered him the opportunity to manage his farm, he jumped at the chance and credited his wife with agreeing to move to Maryland and have an altogether different lifestyle.

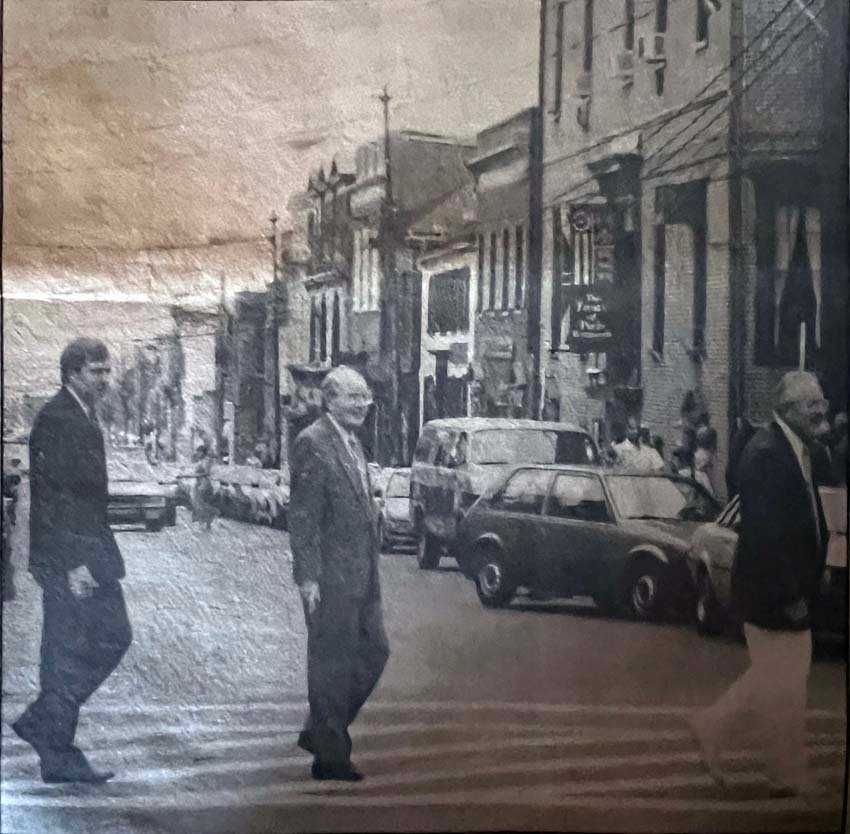

In 1968, Pearson came to Annapolis to go sailing with a friend and saw a beautiful city that was a bit down-at-the-heels. That challenged his imagination. With his passion to create something new, as was the pattern of his life, he became a developer and restorer of great colonial buildings. “I look at an old building and I see a challenge,” he once said to the Washington Post in a 1984 interview.

In one of America’s oldest cities, there were many old structures to choose from—today, Annapolis hosts 120 eighteenth-century buildings. Pearson chose five: the Maryland Inn, Reynolds Tavern, and three deteriorating homes that would be converted to inns: Calvert House, State House Inn, and Robert Johnson House.

Pearson and a partner bought the Maryland Inn for $15,000 down on a $400,000 mortgage. Renovations were costly. Layers of cement and plasterboard were stripped away from an employee locker room and beauty salon, revealing the original timbers and brick floors of Hyde’s first house of entertainment in the state. This basement space was transformed into a bohemian rathskeller and jazz club that Pearson named the King of France Tavern. It would bring the city fame for more than 25 years.

Faced with the challenge of attracting people to this new music venue, Paul found jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd at a City Dock festival. Not knowing anything about Byrd, Pearson somehow convinced the renowned musician to join the nascent jazz club—Pearson’s maître d’ at Treaty of Paris said Pearson had a way with words that convinced you that anything you dreamed of could happen. In May 1972, Byrd opened the King of France Tavern, and Byrd played for three weeks to standing-room-only crowds. It marked the beginning of a 25-year relationship for the Charlie Byrd Trio—with Joe Byrd on bass and Stef Scaggiari on piano. The club was Byrd’s home base until his death in 1999.

The jazz club transformed the Inn into a popular nightspot and city economic generator. Businessman Buddy Levy credited the King of France Tavern with bringing a new vitality to the business district. Ever the visionary, Pearon even planned, in cooperation with Maryland Hall, a weekend with Count Basie that included a gala dance party at the Calvert House.

After Byrd’s death, the club closed and was later converted into a coffee shop. Pearson died in 2001 after suffering six years of debilitating strokes, and the music seemed to die with him.

Today, Kenneth White, current manager of the Maryland Inn, hopes to bring the place back to its former glory, including featuring local and national jazz artists at the King of France Tavern. Drummer’s Lot Pub, where town leaders used to gather, is now open, and in 2024, the Treaty of Paris will reopen. Perhaps “Meet me at the Inn” will become familiar once again and the Inn will come alive with music, helping to usher in a third golden age in this fair city.