+ By Janice Hayes-Williams

The electoral district, once known as the 3rd Ward of Annapolis, was an undesirable area of town during the later part of the 19th-century. Bounded by Dorsey Creek (now College Creek), its thick clay was the foundation for brickyards, railroads, St. Anne’s Cemetery, and a jail at Calvert Street. This became home to many immigrants, as well as a large portion of Annapolis’ Black population of former slaves, free Blacks, and veterans of the American Civil War.

Several events accelerated the growth of this once multicultural community. The founding of the Stanton Colored School, which was built with the wood removed from Camp Parole during its demolition, provided a new school for the city’s large, growing Black population. Continued acquisitions of city property by the U.S. Naval Academy included land along King George’s Street and the demolition of numerous “Negro Tenements,” which necessitated the relocation of a large number of Blacks to Ward 3.

This small community of minorities was in no way immune to the indignities and disparate treatment of Jim Crow racism in the city. Into the 20th century, Black men incarcerated in the Annapolis City Jail were, on numerous occasions, taken from the jail and then lynched. Never forgotten was the lynching of Henry Davis dragged from the jail on Calvert Street, and brought down Clay Street to Brickyard Hill, where he was hanged,and shot multiple times.

This small community of minorities was in no way immune to the indignities and disparate treatment of Jim Crow racism in the city. Into the 20th century, Black men incarcerated in the Annapolis City Jail were, on numerous occasions, taken from the jail and then lynched. Never forgotten was the lynching of Henry Davis dragged from the jail on Calvert Street, and brought down Clay Street to Brickyard Hill, where he was hanged,and shot multiple times.

Surviving the worst of things, this community thrived and continued to grow. At the turn of the 20th century, Blacks and Jews in Annapolis invested in the rapidly growing 3rd Ward in anticipation of further expansion of housing. The community was expanding “over the hill,” as it was called by the locals, with the addition of Pleasant Street and other roads soon to be a part of redistricting, at which point it was renamed the 4th Ward of the city of Annapolis.

During the first decades of the 20th century, past Alderman and entrepreneur Wiley H. Bates made significant purchases along Clay, Washington, and Calvert Streets. Bates leased a few properties and sold others to young Black entrepreneurs looking to start businesses in the 4th Ward. Alderman James Albert Adams purchased a significant amount of land at the end of Clay Street that was bounded by the creek and the Short Line; growing up, we all knew this place as Adams Park.

With churches, movie theaters, saloons, and entertainment, the 4th Ward became a self-contained community of minorities in the city by the 1930s. The Washington Hotel, owned by Morris Legum, quickly became a hot spot known for a variety of entertainment, from sultry signers like Pearl Bailey to female impersonators, local musicians, and ventriloquists.

With churches, movie theaters, saloons, and entertainment, the 4th Ward became a self-contained community of minorities in the city by the 1930s. The Washington Hotel, owned by Morris Legum, quickly became a hot spot known for a variety of entertainment, from sultry signers like Pearl Bailey to female impersonators, local musicians, and ventriloquists.

The late Edward “Udie” Legum, son of Morris and manager of his father’s hotel, revealed that he received great pleasure in telling U.S. Naval Academy officers that shows at the Washington Hotel were sold out when in fact they were not. He said that he would not entertain the officers because Blacks in Annapolis were not given that courtesy at Carvel Hall, the hotel that was once William Paca’s house. “Fair is fair,” he was known to say with a smile.

Through the years, a number of entertainment venues thrived in this community: Susie’s Tea Room, the USO (United Service Organizations), Dixie Hotel, Wright’s Hotel, and Haskin’s, among others. Waltz Dream Hall was used locally for receptions, weddings, and other family gatherings.

The 1940s ushered in a revival of the community. President Roosevelt selected Annapolis to participate in the war effort, revealing a need for health care services and housing for workers. The 4th Ward received housing—College Creek Terrace was the first public housing in Maryland and the second in the nation. It was immediately followed by Obery Court.

Within this community of doctors, attorneys, teachers, entrepreneurs, and employees of the U.S. Naval Academy and St. John’s College was an enigmatic preacher, a spiritual and community leader named Reverend Leroy Bowman. Called to serve at First Baptist Church of Annapolis on Washington Street in 1943, his leadership and influence affected the life of all Blacks in the city, and his fiery sermons could be heard on Sundays at Washington Street.

The 1950s and ’60s brought in an era of civil and equal rights awareness and greater attention to local politics. Residents voted and organized sit-ins, marches, and protests of restaurants and stores that did not allow Blacks to patronize them.

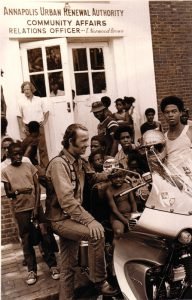

On the heels of the civil rights movement, the fight for human rights began with the advent of urban renewal. That program resulted in the demolition of 33 businesses and numerous homes. To accommodate that loss, public housing communities sprang up, including Robinwood, Newtown 19, Newtown 20, Harbor House, Annapolis Gardens, and Bowman Court. The final act that decimated this vibrant community was the building of the Whitmore Parking Garage at Washington, Clay, and Calvert Streets. “Urban removal” was complete, and as a result, Annapolis had the highest number of public housing units per capita in the nation.

On the heels of the civil rights movement, the fight for human rights began with the advent of urban renewal. That program resulted in the demolition of 33 businesses and numerous homes. To accommodate that loss, public housing communities sprang up, including Robinwood, Newtown 19, Newtown 20, Harbor House, Annapolis Gardens, and Bowman Court. The final act that decimated this vibrant community was the building of the Whitmore Parking Garage at Washington, Clay, and Calvert Streets. “Urban removal” was complete, and as a result, Annapolis had the highest number of public housing units per capita in the nation.

The 21st-century ushered in another revival of the Old 4th Ward, on the wings of the late Bertina Nick. Founder of the Clay Street Community Development Corporation, she ensured that the Ward’s history would never be forgotten. The Old 4th Ward kiosk, located at the corner of Washington and West Streets, is her dream realized. It announces, “Our history, our legacy!” Today, revitalization continues, with public-private partnerships and the Local Organizing Committee of the Old 4th Ward. They work to continue their legacy of brotherhood and dignity.

Although the neighborhood is now legally within Annapolis’ 2nd Ward, it will always be known by many as the Old 4th Ward! █