+ By Dylan Roche + Photos by Alison Harbaugh

“Ms. Brino, do you still have that art group you’re doing at Maryland Hall?”

Luis Bello was not someone Laura Brino expected to see at Bates Middle School on that afternoon in 2015, but there he was—the student who, as a sixth-grader, had shown so much interest and promise in art when Brino taught him, the boy who had fallen in with the wrong group of kids and got into serious trouble, the youth who later had to go off to a juvenile detention center. Here he was, now 15 years old and returning to seek guidance from a teacher he respected.

“He told me he had been doing some art and performing poetry, really working on cleaning his life up,” recalls Brino. “He joined Jóvenes Artistas, our program at Maryland Hall [for the Creative Arts], and we really saw something special in his ability to express himself.”

This reconnection between teacher and student marked an important moment not only in Bello’s career as an artist but also in his direction in life. Now 22 years old, Bello has not had a carefree or easy life, but he has found that honing his talents as an artist has balanced him out, helped him deal with emotions, and given him focus.

He often refers to “coming back” to Annapolis, meaning his return from his time at juvenile detention and Sheppard Pratt hospital, when he faced the challenge of rebuilding his life at age 15. “Miss Brino was my middle school art teacher and a mentor, so when I came back, she was one of the first people outside of my family that I went to visit,” he says. “I overall enjoyed being back in a familiar environment with positive people around.”

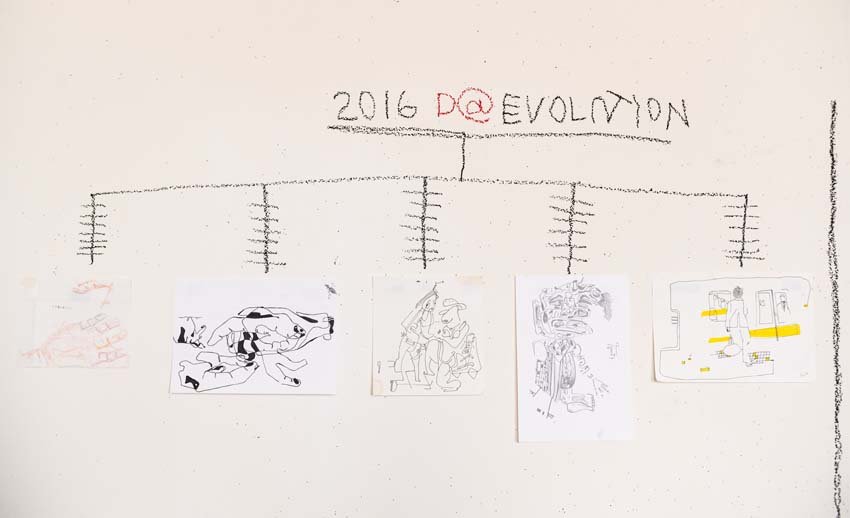

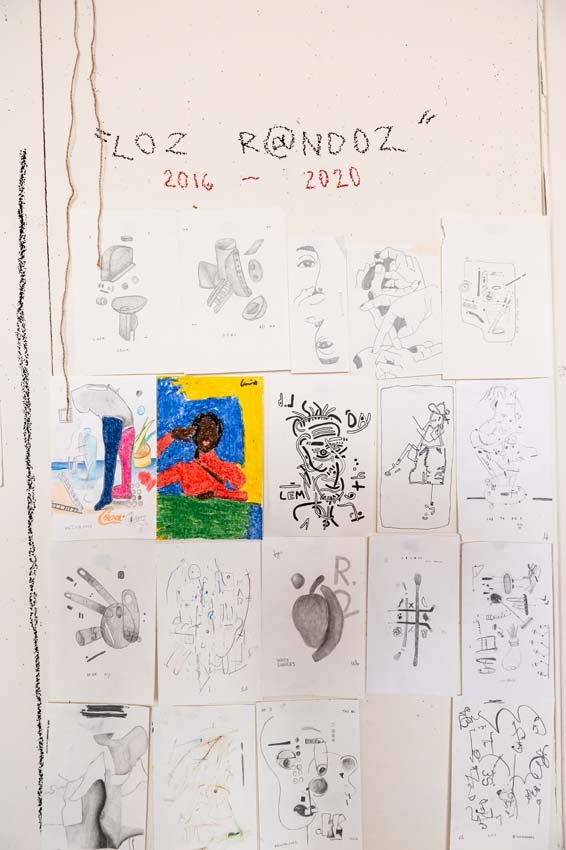

That was why he sought out the chance to participate in Jóvenes Artistas, an after-school program that Brino leads at Maryland Hall to give at-risk youth a place to gain a better sense of self through artistic expression. The program provided Bello the chance to flourish, and he started developing his own sense of style. “Like a true artist, he dives completely into his work and the process,” says Brino. “His style continues to evolve with each phase or stage of the process . . . . Since I’ve known him, I’ve seen five or six different collections of work in different styles. His style is definitely his own.”

Jóvenes Artistas was hardly the first place where Bello was introduced to art, but it was there that he first started taking it seriously. He recalls when he was very young and living with his grandmother in Mexico that he would color pictures, which he would then mail to his mother, who was living in the United States. “Taking into account that that’s my earliest memory, I’d say that’s when I discovered art,” he says. He fondly remembers one particular drawing—it had his mother, a slide, some grass, and a circular sun depicted in the upper right corner of the paper.

But real life wasn’t as happy as the scene he captured in drawings. He still doesn’t know exactly what happened, but when he still very young, he was sent from Mexico to the United States. “My grandma was crying, and I was crying, and then I was gone—on a bus at one o’clock in the morning,” he explains. “They dropped me off at my mom’s job at the time, and then I spiraled into my own little chaos.”

His trouble started when he was in sixth grade. His innocent childhood in Mexico had been replaced by a world where there was overwhelming pressure to be cool. He stopped focusing on school and instead focused on impressing his peers. “When sixth grade was over, I ended up hanging out with the wrong crowd and joined a gang,” he says. “From that point, it got worse and worse.”

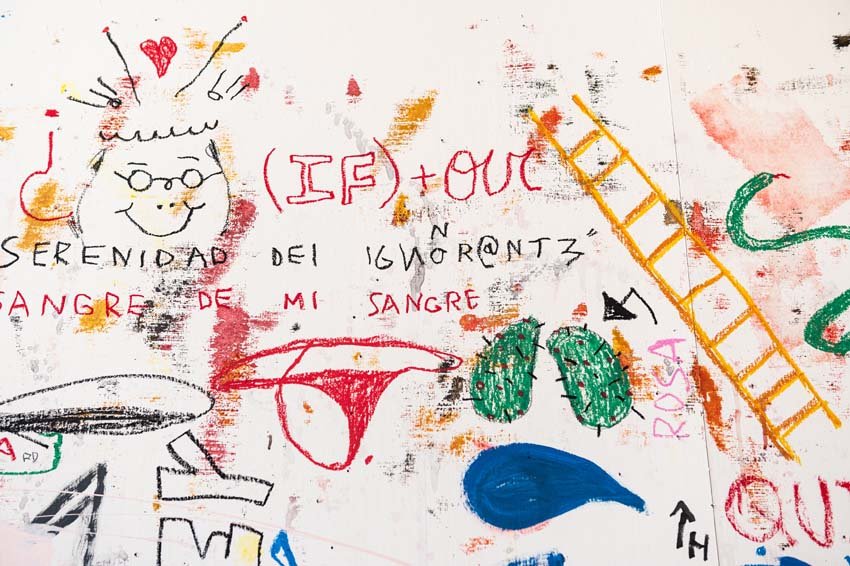

After that, he was placed in the foster care system before going to rehabilitation. “Being in the system played a huge part in the [art] pieces I’ve made in the last few years,” he says. “A lot of the references I make are regarding that specific part of my life, as I was introduced into a lot of real life really quickly. My memory is kind of hazy about those times, which is okay, since I can’t speak of 90 percent of what I do remember. But that’s where my paintings come in. The simplest shapes and lines can fit a whole story.”

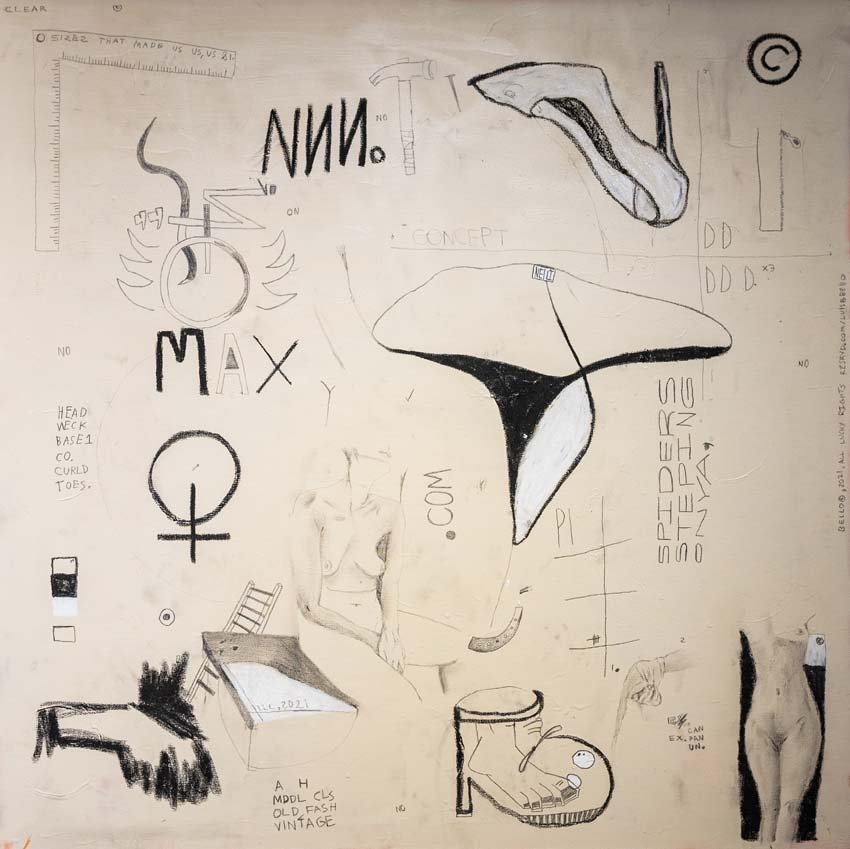

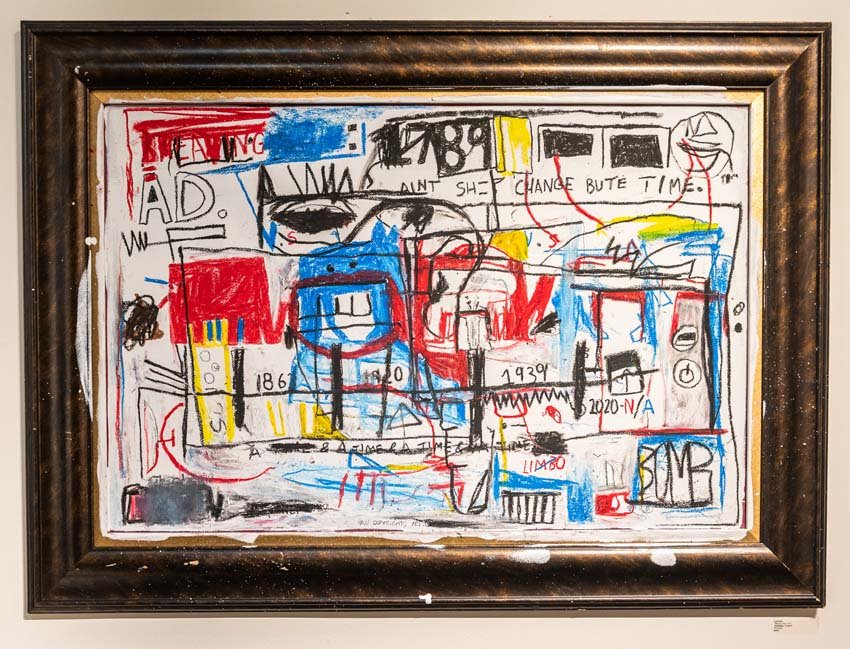

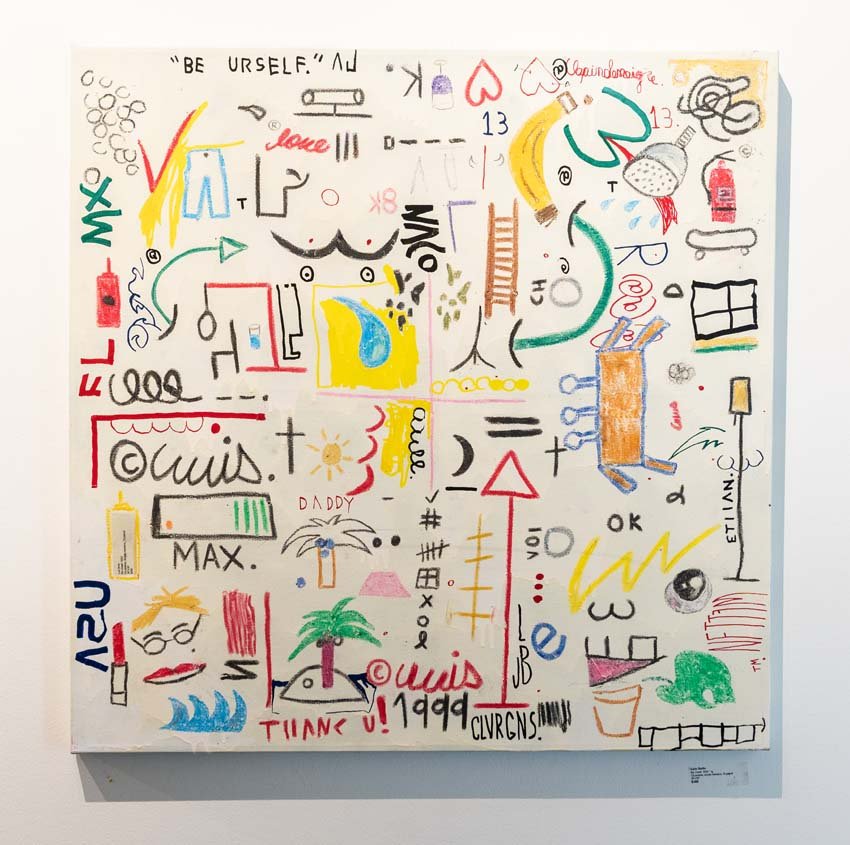

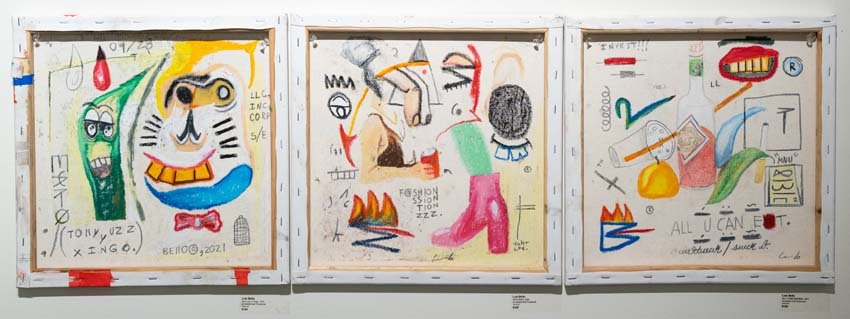

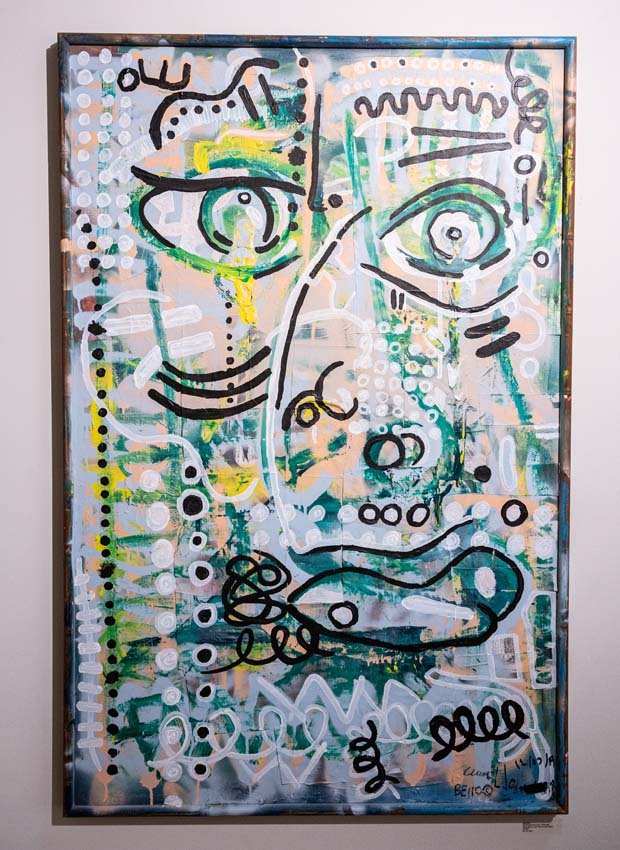

Bello works in mixed media, using everything from acrylic markers to spray paint, allowing all of his thoughts and emotions to fuel the creative process. His feelings about things such as life trauma and sexuality come out as he’s working. “It’s not even to make me feel better,” he says. “It’s just a thing to do, rather than just sit there with rushing thoughts.”

His style reflects the way his mind works, as he puts it. A stroke of paint or ink could be prompted by random song lyrics, euphoria, fear, choices, or regrets. “[They are] all piled up on top of each other, making the messiest yet organized collage of just everything I personally feel, believe, admire, think or whatever,” he explains. “Sometimes, I just vent onto the canvas.” The paintings combine lines and shapes, bright colors, black contours, and a sense of movement and chaos. Faces and facial features—eyes, noses, and mouths—appear prominently.

Those who see the result of Bello’s outpouring of emotion on canvas respond favorably. Brino has observed something special in his paintings since he was a teenager starting out in Jóvenes Artistas. “I can’t put my finger on what it was, but there was something unique in his minimalist approach and unlike what other artists at his age were doing,” she says.

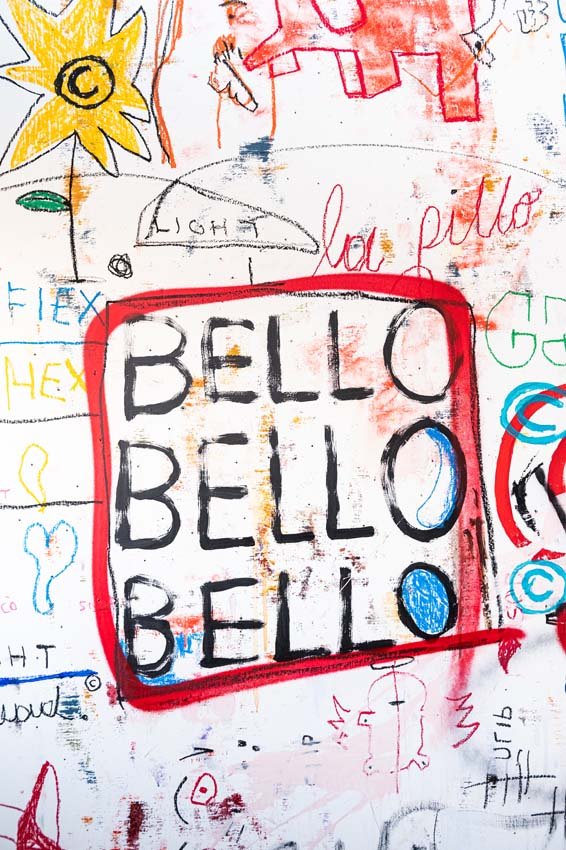

Despite how personal his work is—or maybe, rather, because of how personal it is—Bello enjoys engaging with others about his art, something he has had the chance to do through exhibits at Maryland Hall. “I like sharing my work because no one really knows what they’re looking at, and most of the time, I’m just as confused. I’m just glad it shows and it’s not all in my head . . .” he says.

While several collectors have bought his work, for Bello, it’s not about the money. He sold his first piece when he was 16—one of the paintings he did for Jóvenes Artistas —but expresses underwhelm about that whole idea. “I’m not entirely sure of how I feel toward selling what I make, but I’m also not sure what else to do with them,” he says.

Brino has observed that in Bello. She notes that his commitment to these exhibits and to telling his story is about connections rather than commerce. “He really is interested in connecting with people one-on-one,” she says. “You won’t see him paying a bunch of money to be an art vendor or anything like that. He doesn’t want a ton of limelight, but he is interested in sharing his story.”

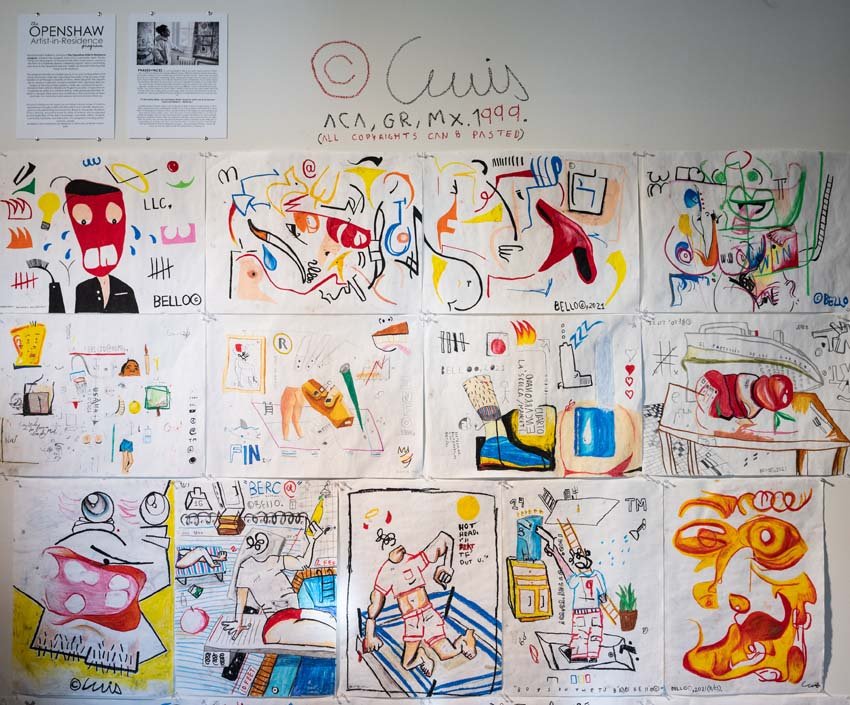

Most recently, Bello’s work was displayed at Maryland Hall from February through May 2022, in a show called Phases and Faces: Paintings by Luis Bello. The show is significant in that debuts Maryland Hall’s Openshaw Artist-in-Residence Program, which brings in new visual artists every couple of months. It’s a milestone for both Bello and Maryland Hall. “As an organization, we are moving full-speed ahead toward community-driven programming and encouraging more diverse artists to share exactly what they want to share,” says Brino.

As for Bello, he will be content as long as he has access to paint and a blank canvas just waiting to be filled. He can’t yet fully make sense of his past, but he sees art as a way of creating a better future for himself. “Art has changed my life, because in order for me to create, I have to remember and portray it in a way I understand it,” he says. “And be okay with nobody else understanding it. It’s kind of therapeutic.” █

Follow Bello’s artistic endeavors on Instagram at @luisbbello.