+ By Julia Gibb

The term retired applies only loosely in describing Tony J. Spencer’s current status in life. There is certainly nothing retiring about his personality. The artist is animated as he speaks about his family legacy, his life, and his art. He pops out of his chair to retrieve a portfolio and point out the details of one of his paintings, or to give a tour of the many spots in and outside of his home that serve as his creative spaces. Despite his outgoing demeanor, he needs time to recharge amid the many activities that keep him busy and engaged in his community. But he doesn’t have any plans of slowing down, saying, “The day you stop learning is the day you die.”

Spencer’s drive to learn sheds light on his lifetime of fascinating careers and artistic pursuits. He is an accomplished musician, having learned to play at least five instruments and performing as a vocalist with groups such as the Jimmy Smith Trio, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, and War, to name a few. He served in the US Marine Corps, was an Honor Guard to President Nixon, a firefighter, medic, and an arson investigator, worked for several Annapolis mayoral administrations—the list goes on. With a master’s degree from Sojourner-Douglass College, he is an adjunct professor at Anne Arundel Community College and president of Nomads of Annapolis, Inc., an organization dedicated to sending minority youths to historically black colleges. Also a poet and writer, he has contributed articles to the Anne Arundel County Historical Society.

Spencer’s drive to learn sheds light on his lifetime of fascinating careers and artistic pursuits. He is an accomplished musician, having learned to play at least five instruments and performing as a vocalist with groups such as the Jimmy Smith Trio, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, and War, to name a few. He served in the US Marine Corps, was an Honor Guard to President Nixon, a firefighter, medic, and an arson investigator, worked for several Annapolis mayoral administrations—the list goes on. With a master’s degree from Sojourner-Douglass College, he is an adjunct professor at Anne Arundel Community College and president of Nomads of Annapolis, Inc., an organization dedicated to sending minority youths to historically black colleges. Also a poet and writer, he has contributed articles to the Anne Arundel County Historical Society.

Born and raised in Marley, a neighborhood in Glen Burnie, Spencer’s passion for art was sparked by a beloved high school art teacher, Louis Schatt. He warmly recalls Schatt’s special way of pushing him out of his artistic comfort zone. “If he didn’t agree with something [on a student’s canvas], he’d just say, ‘Uhhh . . .’ and walk away.” Spencer received the “Uhhh . . .” treatment once, while working on a painting with raspberry hues. “I was frustrated, so I took spray paint and just did a light coat of black over it. [Mr. Schatt] came back over and said, ‘Yes!’” he laughs. Spencer was surprised and delighted when his former teacher showed up for the opening of his 2016 exhibit at 49 West Coffeehouse, Winebar & Gallery, and the two picked up as if decades had not passed.

Spencer’s home displays works by locally and internationally known artists. Several pieces by Alonzo Davis, including a painted bamboo wall sculpture, adorn the living room. A print by prominent Washington Color School painter Sam Gilliam hangs near the stairwell. Spencer’s admiration for these artists comes through in his bold use of color and shape. He also extolls the creations of Salvador Dali for exemplifying ultimate creative freedom. In 2003, Spencer and his wife, Vivian Gist Spencer, visited the Dali Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain. There, the sculpture garden, the collection of works by artists that inspired Dali, and the sheer range of Dali’s own work reinforced Spencer’s quest for unfettered expression in his own art. “[Dali] didn’t limit himself, and he understood that if it took just one dot to make a message, that’s what he did,” says Spencer.

An even more profound influence on Spencer’s worldview and work is his remarkable family legacy. His great-great-grandfather, Captain James William Spencer, was born a free African American in Maryland around the year 1817. In an unprecedented undertaking for his times, he started purchasing land. One of those parcels, located in the area now known as Marley, would become Freetown, one of the largest communities of free blacks outside of Annapolis. Captain Spencer, who had to carry a certificate proving his freedom at all times at the risk of being sent into slavery, found a way to pursue freedom within a slavery-driven society, as owning land created personal and community agency. He went on to fight for the Union in the Civil War.

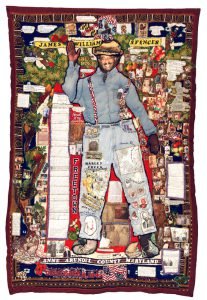

“James William Spencer Documentary Quilt” is an important work of Spencer’s that honors his family legacy. It uses images to tell the story of Freetown and the descendants of Captain Spencer, up to the present day. With the help of Dr. Joan M. E. Gaither, an artist, educator, and master quilter who specializes in storytelling quilts, Spencer worked on the piece with a team that included his wife, Vivian, several other family members, and Alderwoman Sheila Finlayson for three to four months. Recalling the immersive experience he says, “You sit down for one hour to work on the quilt, you look up, and believe it or not, three hours have gone by!” The quilt has been part of exhibits at the Benson-Hammond house in Linthicum, Annapolis City Hall, and the Whiley H. Bates Legacy Center, and was recently at Anne Arundel Community College as part of Spencer’s solo exhibit, TRYBE-ALL CELEBRATION, in recognition of Black History Month.

“James William Spencer Documentary Quilt” is an important work of Spencer’s that honors his family legacy. It uses images to tell the story of Freetown and the descendants of Captain Spencer, up to the present day. With the help of Dr. Joan M. E. Gaither, an artist, educator, and master quilter who specializes in storytelling quilts, Spencer worked on the piece with a team that included his wife, Vivian, several other family members, and Alderwoman Sheila Finlayson for three to four months. Recalling the immersive experience he says, “You sit down for one hour to work on the quilt, you look up, and believe it or not, three hours have gone by!” The quilt has been part of exhibits at the Benson-Hammond house in Linthicum, Annapolis City Hall, and the Whiley H. Bates Legacy Center, and was recently at Anne Arundel Community College as part of Spencer’s solo exhibit, TRYBE-ALL CELEBRATION, in recognition of Black History Month.

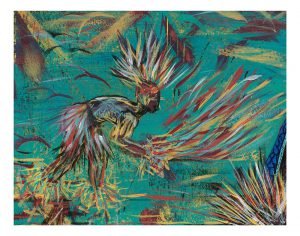

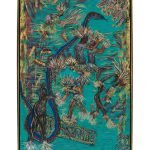

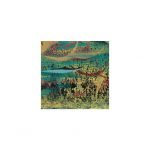

Spencer’s paintings, prints, and drawings are filled with references to his heritage. One painting, “Trybe-all,” is populated by warriors in traditional garb against a rich aqua background, with a large serpent sprawling across the diagonal of the canvas. “Forest of my Ancestors” depicts a stand of woods that now grow on the land that once belonged to his great-great grandfather. Hidden in the woods are faces and figures, including one figure hanging from a tree. Encouraged by Gaither to find “paintings within paintings,” Spencer meditates on details within larger compositions, and with them he creates new pieces. One such piece, “Bush Church in the Wilderness,” was created from a detail of “Trybe-all” and pays homage to enslaved African Americans who were forced to find ways to worship in private, in “bush churches.”

For Spencer, the art-making process is flexible, forever evolving, and takes him in new directions. Nothing is set in stone, and the best-laid plans might be cheerfully forgotten as inspiration takes over. For him, art means surrendering to a power greater than himself. “Can you understand being a channel,” he asks, “and allowing things to flow?” This approach fuels the constant evolution of his work. He may print paintings or sections of paintings onto archival paper or canvas so he can add paint back into the new compositions. A sketch done on a paper towel might end up printed onto canvas so that it can be further developed. He has a nomadic approach to his creative space—his easel might start in his living room and then travel to the sunroom near the bar or out to the back deck, depending on the light.

Underlying the freedom in Spencer’s work is a foundation built on the bedrock of his faith and his respect for his ancestral legacy. Referring to his great-great grandfather, a visionary of his time, Spencer says, “I stand on his shoulders today.” Spencer also wants to help children realize the power of their cultural foundation, saying, “[Africans] didn’t come here [only] as slaves. They came here with a society in their heart, in their DNA.” He emphasizes the importance of educating current and future generations of their rich history, giving them a sense of place in the world. “Until they understand that,” he says, “they think, ‘I’m nothing.’”

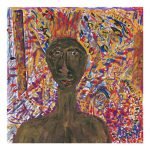

Spencer recounts the story behind “African Warrior,” a portrait of a warrior with a fierce and fiery-looking Mohawk, surrounded by bright, swirling colors, textures, and shapes. He notes that most people assume the subject is male. “The only ones that got it were two elementary school kids and one adult, who saw a woman right away.” The warrior has a peaceful expression with a hint of a smile. “In the middle of chaos, she’s sturdy,” says Spencer. “She knows what she has to do, and she remains calm.” █

Look, listen, and learn more at www.enrapture51.com.

- AfricanWarrior, 7/6/15, 10:31 AM, 8C, 8000×8572 (0+705), 100%, Custom, 1/30 s, R55.3, G12.7, B26.1

- Tribal6, 5/1/15, 3:35 PM, 8C, 7962×9735 (36+696), 100%, Custom, 1/60 s, R41.9, G0.0, B13.2

- Tribal6, 5/1/15, 3:35 PM, 8C, 7962×9735 (36+696), 100%, Custom, 1/60 s, R41.9, G0.0, B13.2

- Tribal6, 5/1/15, 3:35 PM, 8C, 7962×9735 (36+696), 100%, Custom, 1/60 s, R41.9, G0.0, B13.2

- SwingingOnTheBack9(two), 7/6/15, 9:44 AM, 8C, 6692×9047 (603+705), 100%, Custom, 1/30 s, R55.0, G12.4, B26.8

- ForestofMyAncestors, 7/6/15, 11:47 AM, 8C, 8000×8572 (0+705), 100%, Custom, 1/30 s, R55.3, G12.7, B26.1