+ By Julia Gibb + Photography By Karen Davies

In her Highland Beach home studio, Lilian Thomas Burwell leans against a cheap table she altered to serve as a sturdy work surface, sharing stories of faith, family, and art. Her gregarious tabby cat, Mikey, scales her slim frame to nestle into her arms. Scolding him for being spoiled, she accommodates him. At 89 years old, the artist battles three degenerative spinal diseases that should have had her wheelchair-bound years ago. Despite her ever-changing physical condition, she shows no sign of slacking off on what she considers a spiritual duty: to be a medium between her Creator and her community, sharing messages of resourcefulness, resilience, and hope.

Born in Washington, DC, Burwell’s artistic story truly begins with the stock market crash of 1929, which precipitated her family’s move to New York City. She has vivid memories of her mother fashioning block-printed curtains out of cast-off pongee silk sacks used for shipping fabric from Japan, and spectacular dresses out of the still-good parts of worn sheets. She and her brother created toys and books for themselves out of wooden produce crates and discarded magazines. Burwell’s resourceful spirit was forged in this environment; she came to take almost for granted a person’s ability to create whatever was needed out of practically nothing, and to make those things wondrous.

Burwell hails from an artistically inclined family—her father was a photographer, her mother was an artist and craftsperson, and her aunt, Hilda Wilkinson Brown was a renowned painter. But when Burwell expressed an interest in pursuing an arts education, her parents thought she had “lost what little mind she had,” she laughs with her whole body, bringing straight, tapered fingers to cover her mouth. Her aunt convinced her parents that Burwell should pursue teaching art as a career so that her income could support her passion to create art. To this day, Burwell credits that decision for giving her the freedom to be an artist. Brown and her husband augmented the partial scholarship that Burwell received from the School of Art at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and helped pay for her art materials and books. She later returned to Washington, DC, and earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting at Catholic University in consortium with American University. During those years, Burwell married, gave birth to her daughter, Lilian Elizabeth, worked commercial design jobs, taught art at several schools, and exhibited her work in solo and group shows.

Burwell hails from an artistically inclined family—her father was a photographer, her mother was an artist and craftsperson, and her aunt, Hilda Wilkinson Brown was a renowned painter. But when Burwell expressed an interest in pursuing an arts education, her parents thought she had “lost what little mind she had,” she laughs with her whole body, bringing straight, tapered fingers to cover her mouth. Her aunt convinced her parents that Burwell should pursue teaching art as a career so that her income could support her passion to create art. To this day, Burwell credits that decision for giving her the freedom to be an artist. Brown and her husband augmented the partial scholarship that Burwell received from the School of Art at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and helped pay for her art materials and books. She later returned to Washington, DC, and earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting at Catholic University in consortium with American University. During those years, Burwell married, gave birth to her daughter, Lilian Elizabeth, worked commercial design jobs, taught art at several schools, and exhibited her work in solo and group shows.

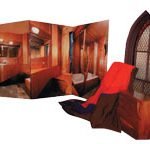

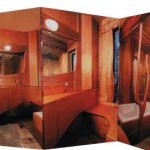

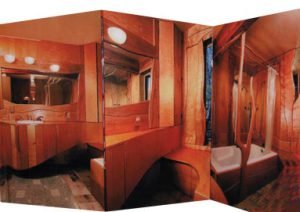

In the mid-sixties, Burwell studied abstract expressionism with famed artist Benjamin Abramowitz. She worked in this genre, painting on stretched canvas, until the early eighties. Following the death of her mother, who had spent her last year under the artist’s care, Burwell found herself paralyzed with grief and unable to work in her studio. She became absorbed in a project that sprang organically out of the simple necessity of hanging a large bathroom mirror. She carved a curvaceous wooden mirror frame and then, piece by piece, created her first sculpted wood bathroom. By doing so, she was expanding on her personal understanding of an expression she had heard from her elders, “[Finding a] way out of no way.” Ignoring those who admonished her not to make a wood bathroom because of the dampness of that environment, she carved and shaped pieces of wood, paneled all the walls with them, encased the toilet tank, and created countertops.

The process freed her to approach artistic challenges in a new way. She was drawn back to an abandoned two-dimensional painting that she had tried repeatedly to resolve without success. Instead of painting over the problematic section, she cut it away and then constructed a framework to support the cut canvas from the back. This improvisation gave birth to “paintings as sculpture”—her current mode of expression.

The process freed her to approach artistic challenges in a new way. She was drawn back to an abandoned two-dimensional painting that she had tried repeatedly to resolve without success. Instead of painting over the problematic section, she cut it away and then constructed a framework to support the cut canvas from the back. This improvisation gave birth to “paintings as sculpture”—her current mode of expression.

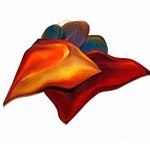

Burwell’s paintings as sculpture are carved out of pieces of sugar pine, covered with canvas, gessoed, and painted upon. As she works now, she allows the work to evolve in a point-and-counterpoint process. She likens it to a dance, the second direction of her shaping tool—and eventually the paintbrush—responding to the first. Upon completing a composition, she may hang a smaller shape from the ceiling by monofilament in front of the other shape attached to the wall.

The forms that comprise Burwell’s compositions are evocative of nature and movement, appearing simultaneously solid and fluid. A single shape may resemble a scapula and, at the same time, a bird in flight. Brushstrokes and colors call to mind the solidity of mountains or the flow of water.

The forms that comprise Burwell’s compositions are evocative of nature and movement, appearing simultaneously solid and fluid. A single shape may resemble a scapula and, at the same time, a bird in flight. Brushstrokes and colors call to mind the solidity of mountains or the flow of water.

Burwell recently curated and featured in “The Art of a People: Finding a Way Out of No Way” at the Banneker-Douglass Museum in Annapolis. Eight African-American artists and a poet created original works, exploring themes of slavery, racism, survival, and heroism in the face of adversity. The works were reproduced, and installed as adhesive murals in the museum’s second-floor gallery. Burwell’s massive installation, Orison Piece, was displayed in the first floor gallery as the exhibit’s prelude.

As accompaniment to her visual art, Burwell writes eloquently about the meaning of her work and the creative process. She has published a book of poems, A Dichotomy of Passions: the Two Masters, and an autobiographical book about the evolution of her work, From Painting to Painting as Sculpture: the Journey of Lilian Thomas Burwell. In the latter, she explains what drives her to write and create: “I feel compelled to pass on knowledge of the primary forces that have enabled me to find answers critical to survival as a woman, as an African American, and as a person constantly needing to adapt to the new and threatening realities of our times.”

Burwell does not rest on her laurels: after decades of significant accomplishment, she feels as if she is just beginning to learn, create, and teach. In her living room, where everything from her artwork to her furniture bears her personal touch, her phone rings often. She takes calls from family, friends, and other people, offering a helping hand. Connecting with others is essential to Burwell, in life as in art. She considers her pieces complete only when the viewer has a chance to interact with them. “In art, as in life, you have to throw your stone into the ocean—you don’t know where the ripples will go.” █