+ By Theresa C. Sanchez + Photos by Alison Harbaugh

It is generally acknowledged that art is composed of six visual elements: line, shape, form, space, color, and texture. But Annapolis-based artist Ronald Markman would add a seventh component: tone, and specifically, one of whimsy.

“Silly is very important,” says Markman. “There are two things I want to achieve with my work: silliness and making the pieces look really good. That’s what I do. I have to do it.”

The 85-year-old painter has dedicated much of his life to the pursuit of creativity. It all began in New York, in the Bronx, where Markman absorbed every aspect of his childhood environment. His parents exposed him to various forms of entertainment that would become source material for his artwork: from Jack Benny shows and Marx Brothers movies to Smokey Stover comics and Broadway performances, there was no shortage of stimuli.

The 85-year-old painter has dedicated much of his life to the pursuit of creativity. It all began in New York, in the Bronx, where Markman absorbed every aspect of his childhood environment. His parents exposed him to various forms of entertainment that would become source material for his artwork: from Jack Benny shows and Marx Brothers movies to Smokey Stover comics and Broadway performances, there was no shortage of stimuli.

His early graphic interests guided him to train and later work briefly as a cartoonist. But after showing his portfolio to the late famed illustrator of The New Yorker, Saul Steinberg, Markman quickly realized that he had much more to learn. The self-described “writer who draws” was the first of several figures who played a pivotal role in shaping the artist and man who Markman is today.

Markman’s desire and drive to improve his craft led him to the Art Students League of New York. There, he learned the fundamentals of drawing from acclaimed caricaturist George Grosz, who is largely associated with the Dada and New Objectivity movements of the 1920s.

In 1952, he was drafted to serve in the Army during the Korean War, where his talents were directed toward utilitarian tasks. “I painted signs. What else could [they] do with a painter? I was very lucky,” says Markman.

Two years later, upon completing duty and earning the rank of sergeant, he enrolled at the Yale University School of Art on the GI Bill. He studied under the unconventional tutelage of Josef Albers, a visionary geometric abstractionist considered to be the father of color theory and best known for his signature series “Homage to the Square.” Markman earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts, studying color, drawing, and painting over the course of just four years.

Two years later, upon completing duty and earning the rank of sergeant, he enrolled at the Yale University School of Art on the GI Bill. He studied under the unconventional tutelage of Josef Albers, a visionary geometric abstractionist considered to be the father of color theory and best known for his signature series “Homage to the Square.” Markman earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts, studying color, drawing, and painting over the course of just four years.

“Markman recalled Albers insisting that his students find their own vision,” says Andrew Wang, an Indiana University Bloomington graduate student who curated the special installation “After Yale: Pupils of Josef Albers,” which ran from January through August 2016 at the institution’s Eskenazi Museum of Art. Markman was a professor of fine arts at the university from 1964 to 1994. “[He remembers] Albers being very poetic, with creative assignments like creating collages out of leaves to analyze color interactions,” says Wang.

Action was key to Albers’ instruction, and in 1940, he wrote, “Art is a demonstration of human life. Art is revelation instead of information.” He encouraged Markman to step out of his comfort zone to more fully develop his aesthetic instincts and methods. Once, Markman decided to emulate a classmate’s work after being frustrated by the lack of positive feedback in class. “The strategy worked,” he says. “I learned from this experience that copying elements of other art could be a valid way to improve my technique.”

“Albers was a marvelous teacher, and I will always be grateful that I had the opportunity to study with him,” says Markman. “I feel I owe Albers everything.” Additional early influences include Paul Klee, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, and Claes Oldenburg. “You need to learn about yourself and figure out how to translate your self-knowledge into art,” he says. “You don’t want to be like everyone else. You want to figure out what makes your art special and different in a meaningful and imaginative way.”

He finished school in the late 1950s, and hit the ground running with a one-man, sell-out show at the Kanegis Gallery, then in Boston, Massachusetts. The Museum of Modern Art in New York bought one of his drawings and featured it in its exhibit, “Drawings, Watercolors, Collages: New Acquisitions.” It is still part of the permanent collection. In 1960, the Whitney Museum in New York included Markman’s work as part of its “Young Americans” series. That same year, he also started working as a fine arts instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago.

He finished school in the late 1950s, and hit the ground running with a one-man, sell-out show at the Kanegis Gallery, then in Boston, Massachusetts. The Museum of Modern Art in New York bought one of his drawings and featured it in its exhibit, “Drawings, Watercolors, Collages: New Acquisitions.” It is still part of the permanent collection. In 1960, the Whitney Museum in New York included Markman’s work as part of its “Young Americans” series. That same year, he also started working as a fine arts instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Galvanized by his successes, Markman applied for and was granted a Fulbright scholarship to study painting in Rome in 1962. During his year abroad, he discovered printmaking and learned that it appealed to a wider audience than his paintings.

“The work I was doing in my prints was my best work—the best part of me,” says Markman. “I wanted to transfer the quality of that work to painting, and I have tried very hard to do that on a larger scale.”

While in Italy, he frequented local museums and became particularly enchanted with the ancient maps. Cartographic fascination prompted him to invent a country of his very own. “The map had to have a name, so I came up with Mukfa,” recounts Markman. “I wanted something slightly obscene, because the world is obscene, as you probably know.” His website describes it as a “fantasy realm of unbridled absurdity” where his alter ego, Rolland Markum, and a cast of colorful characters exist uncensored in an exaggerated alternative reality. “The content [of my art] is the political and the craziness of the world, and the craziness is what people do to each other. And [it’s] also the beauty of the world and travel—the variety of the world; it’s so complicated. All my work touches upon that, in a way,” he says.

Markman retired from teaching in 1994, about three years after his wife died. During this time, he reconnected with longtime friend and artist, Barbara Cabot, who was also widowed, and the two forged a partnership. When deciding on a place to relocate, they considered the Washington, DC area so that Markman could be close to his daughter Ericka and her growing family. On-site studio space and a laid-back atmosphere were also priorities, so they opted to settle in nearby Annapolis. They moved east in 1998, and once acclimated, Markman returned to painting full-time.

Nineteen years later, Markman is being honored with a presentation of his career’s creations, spanning the course of six decades. “The Fantastic World of Ronald Markman: A Mini-Retrospective” debuts at the Elizabeth Myers Mitchell Gallery at St. John’s College in Annapolis on March 10, and runs through April 23. It will be the first time the hall will have a living artist return to exhibit art. His debut showcase in 2005, entitled “Heroes, Villains, and Mermaids,” was immensely popular and paved the way for a 30-piece show at the Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts in 2010.

Nineteen years later, Markman is being honored with a presentation of his career’s creations, spanning the course of six decades. “The Fantastic World of Ronald Markman: A Mini-Retrospective” debuts at the Elizabeth Myers Mitchell Gallery at St. John’s College in Annapolis on March 10, and runs through April 23. It will be the first time the hall will have a living artist return to exhibit art. His debut showcase in 2005, entitled “Heroes, Villains, and Mermaids,” was immensely popular and paved the way for a 30-piece show at the Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts in 2010.

“There’s no one-word description for Ronald Markman’s work. [For] some artists, you can say, ‘Okay—that’s detailed,’ or ‘that’s colorful,’” says Lucinda Edinberg, art educator at the Mitchell Gallery. “Ron doesn’t fit into any of those categories, and we’re thrilled that he doesn’t.” Markman and Edinberg have chosen 51 items to display in the gallery’s two rooms to highlight his evolutionary path as an artist.

Markman paints with acrylics and is known for repurposing most of his other materials: the aluminum plates he paints on are recycled from the Capital Gazette. Though painting has always been his primary medium, Markman also explored etching and prints in the 1960s and 1970s.

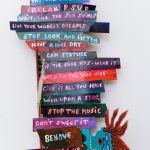

He categorizes much of the artwork on loan for the exhibit as “three-dimensional paintings constructed out of wood,” and considers News Stand (1992, 4′ x 7′ x 2′), Tabloid (2001, ~ 6′ x 8′), Mukvu (2007, 7.3′ x 5.5″ x 2′), and Personals (2007, ~ 5′ x 3′), to be its centerpieces. None of the four has been publicly displayed in Annapolis. Mukgate (2004-5, 11′ x 10′ x 2.5′) is so immense that visitors can walk through its archway. Markman assures me it’s the biggest piece he’s ever made, and he did so with the aid of longtime friend Dr. Richard Malmgren. The two met in 1998, through mutual friends, at a dinner party. The retired cancer researcher mentioned he did woodwork. Both have since joked that it was a match made in heaven, but Markman seriously acknowledges Malmgren as an invaluable collaborator and friend. Much of what is on display that was created in Annapolis is a product of their alliance. Markman would conceive an idea and design a plan. He would then defer to Malmgren to determine how to build the wood and aluminum structure, and eventually paint his concept onto the assembled handiwork. “It’s safe to say many of the pieces that I created over the past 18 years would not exist without his help,” he says.

In an effort to provide a peek at the personal, Markman is also including in the St. John’s exhibit a collage of envelopes from letters he and his late wife sent to their daughter at summer camp. Each cover is embellished with drawings of his favorite characters and themes.

In an effort to provide a peek at the personal, Markman is also including in the St. John’s exhibit a collage of envelopes from letters he and his late wife sent to their daughter at summer camp. Each cover is embellished with drawings of his favorite characters and themes.

“I’m very pleased with what I’m doing now, as opposed to what I was doing 50 years ago. Some artists really do their best work when they’re young,” says Markman, “but it took a long time for me to get to where I wanted to be. Now, I feel very confident in what I do and enjoy it. I just want people to see!” █