+ By Julia Gibb

Greg Harlin leans down until his face is within inches of his drafting table. “When I first started working at a design firm . . . I was really self-conscious about my work, so I’d work like this, and no one could see it.”

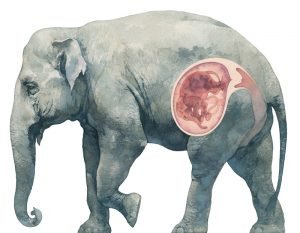

Elephant Pregnancy, late stage

17″x13″ watercolor on paper

For a panel in the new Elephants Lands habitat at the Oregon Zoo.

Vistiors turn a wheel to see stages of fetal development/

His studio is a small, cube-shaped room with one window on the second floor of his Cape St. Claire home. At the center of his drafting table is an intricately detailed watercolor depicting a colonial American scene. The walls are a bricolage composed of drawings, comics, poems, and small objects both natural and manmade, every piece having captured his imagination in some way. “We are all unconsciously writing our autobiographies in what we accumulate,” he says of the collection. The mix of items has a synergy that sparks unexpected ideas, color combinations, and compositions. Its presence is inspiration, not distraction, as he leans in to focus on the tiny details of his illustrations. “I still work like this a lot,” he laughs as he stands back up.

Born on the Fourth of July, Harlin likes to say that his birthdate foretold his career as an illustrator of historical and prehistorical subject matter. Though he wasn’t particularly interested in the subject in school, today he enjoys learning the history behind the scenes that he paints, almost exclusively in watercolor. He researches his subjects with the help of historians, the Internet, and occasionally travel. Harlin’s historic subjects are a natural fit for downtown Annapolis. His painting, John Paul Jones’ Ranger, commissioned by Annapolis’ Art in Public Places Commission, was reproduced onto a large panel that now adorns the wall near Gate One to the U.S. Naval Academy.

Katherine Burke features Harlin as one of six “Annapolis Masters” represented at her Annapolis Collection Gallery, located at 55 West Street. The gallery is part of a group of buildings known as “Gallery Row,” a hotbed of artistic activity and community in the Annapolis Arts District. Harlin’s original works, along with limited edition prints, are on exhibit and can be purchased there. Harlin, along with a fellow Annapolis Master, Roxie Munroe, will be featured in a show at Annapolis Collection Gallery called “Ants and Elephants.” The show opens in November 2017 and runs throughout December of this year.

Hanukkah at Valley Forge

15”x12” Watercolor and Gouache on Gessoed paper.

Cover for the book by Stephen Krensky.

Harlin’s love for watercolor developed as he was working toward a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of Georgia. After graduating, he went immediately to work at a large illustration group in Atlanta, where he found himself working more with graphic design for advertisements rather than illustration. His nature makes him capable of being content in any situation, so when an opportunity opened up at a design studio then known as Stansbury Ronsaville Wood, Inc., it took a little nudge from his mother to convince him to take the job and relocate to Annapolis. Working with this studio opened up a world of illustration jobs to him, and he is now a key partner at the studio, which is currently known as Wood Ronsaville Harlin, Inc.

While Harlin’s work is distinguished by its intricate and historically accurate details, he explains that this is the part he’s most comfortable with. “The tricky thing for me with watercolor is that the big strokes set the mood of the scene,” he says. He describes how he allows the paint to move organically, knowing when to manipulate it, but more importantly, when to leave it alone. The process of creating these “big strokes” can make him nervous, but it allows him to create a contrast between a loose, organic background and tightly rendered figures, architecture, weapons, or ships. The medium has a vitality of its own, and that’s part of what breathes life into a painting of a scene that happened hundreds or thousands of years ago.

Amesbury Archer

5”x8” watercolor and gouache on paper

For “Mystery Man of Stonehenge”, an article in Smithsonian magazine on the discovery of a 4,300 year old skeleton near the monument and the intriguing questions it sparked.

Harlin studied with the renowned local artist Lee Boynton, who passed away in the spring of 2016. Boynton also worked in an illustrative style, and the vigor of his style and color palette remains a major influence on Harlin’s work. A collection of pieces by other local artists whose art inspires him hangs on his kitchen and living room walls. Lee Boynton’s daughter, Margie Boynton, who trained extensively with her father, and artist M. Jordan Tierney feature in the collection. He points to a piece on his wall by Tierney, explaining that the dark, deep blue that dominates the canvas invokes a sense of forlornness, yet subtly painted birds near the top seem to move in an upward curve, suggesting hope. Harlin places a book he illustrated—Hanukkah at Valley Forge, by Stephen Krensky—on his kitchen table and opens it to a winter scene rendered in cold, blue monotone. A colonial American soldier walks in the foreground, bracing himself against the snowy weather, head down against the wind. In a cabin on the left side of the composition, warm, orange light fills the narrow space of a slightly open doorway, hinting at respite and comfort inside. “You just make the painting as miserable as you can,” he says of the piece, “but that little bit of something bright just makes it okay.”

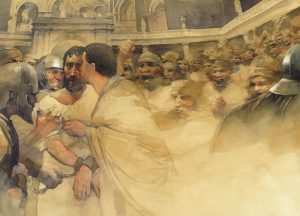

In the illustration Origen’s Kiss, one piece of a series created for the multivolume book, The Christians, Harlin creates dynamism by contrasting stillness and motion. In the piece, Origen, an early Christian theologian, stands with a student of his who is about to be martyred, comforting him with a “kiss of peace.” Guards flank the martyr, ready to escort him to his destiny. On the right, an angry mob appears to be ready to overwhelm the small group, figures blurred with motion, facial features distorted with bloodlust. The distinct parts of the piece create tension and balance at the same time. “One couldn’t stand without the other,” says Harlin.

Sketchbooks serve Harlin as a format in which he explores personal experience and processes moments from his life that leave an indelible impression on his psyche: a painted sketch of his father resting in an armchair, looking imposing and formidable; a favorite workplace he had as a child; a small cubicle in the basement of the family home where he used to sit in the warm lamplight at his desk. He turns to an illustration he did for Lynne Cheney’s book, We the People: The Story of Our Constitution. There is James Madison at work at his desk, looking much like Harlin’s memory of his own hours spent working in his cubicle. “Your own experiences find a way in. It might not matter to anyone else, but it makes you feel like you’re there.”

Origen’s Kiss

18”x13” watercolor on paper

Origen, an early Christian Theologian comforting Martyrs.

Part of an illustrated book series on the history of Christianity.

Down the hallway, the doorbell rings. A colleague is dropping off watercolors that Harlin is working on for the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. The pieces have been scanned and will be reproduced as large murals. He lays a painting on the kitchen table, where the late afternoon sun streams through a nearby window. It is a colonial Philadelphia street scene. In addition to exquisitely rendered clothing and figures of white colonial Americans, an African American, and several Native Americans, the architecture is rendered in mind-boggling detail. Every brick on several of the buildings is painted individually and to scale.

“People make fun of me,” he says of his obsessive nature, “but I didn’t know how [else] to do these!” He explains how he added touches of paint later with a natural sponge to give the bricks a more organic feel. Harlin says that his girlfriend, Kim Eshleman—whom many Annapolitans may recognize from the local art supply store Art Things as well as from her guitar playing and vocals in the band Johnny Monet and the Impressionists—gave him an apt insight. “She said it’s like knitting”—minutiae as meditation. █