+ By Ellen Moyer

The performing arts thrive in Annapolis and have done so since the time when it was called “The Athens of America” and proclaimed by visitors as “The Bath of America.” High praise indeed for a town of 1,000 citizens that had been recently carved from the Chesapeake Bay wilderness.

Ancient Athens, Greece, birthplace of democracy, was a center of arts, learning, and philosophy. Eighteenth-century Bath, England, visited by Princess and Queen Anne (Annapolis’ namesake), was a center of social elegance, with concerts, opera, and theater. In the colonies, Annapolis had that reputation, leading government official William Eddis to proclaim, “[T]here is not another town in England . . . which can boast of a greater number of fashionable and handsome women”1 who displayed their grace at numerous balls and race week activities.

The Quakers and Puritans in the northern colonies viewed theater as a pathway to hell, and in New England, laws were passed that forbade theater productions. Below the Mason-Dixon line, however, theater found fertile ground in Annapolis. In a town that idolized the English gentry, Reverend Jonathon Boucher would exclaim in his autobiography Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, “I hardly know a town in England so desirable to live in as Annapolis.”

In the 1750s, theater fostered a thriving, cultural city. The companies were family affairs. Elihu Riley, writing in The Ancient City, noted that “the first theater in America was built in Annapolis and the first production, The Beggars Opera, opened on June 18, 1752.” Managed by Murray and Kean, one of the first professional acting companies in the New World, they stayed in Annapolis, producing performances of Cato and Richard III. The Hallam Company, noted by some as the first fully professional theater to perform in America, had been respected performers in London’s Coventry Gardens. In 1760, the entire company came to the colonies and Annapolis. John Palmer, a favorite in Drury Lane comedy, performed here.

By 1771, Annapolis had its own performing arts center on West Street, on property owned by St. Anne’s Church. It was the first playhouse in North America. Of it, William Eddis wrote, ”[O]ur new theater . . . boxes were commodious and neatly decorated . . . performers well above mediocrity.”2 Its green velvet curtains scrolled up, giving us the term “curtains going up.” Above the stage, “the whole world Acts the Player” was inscribed. Annapolis scored another first when the first critical opinion and detailed criticism on the performance of Cymbeline appeared in the Maryland Gazette. Theater was considered good business for the city. Tickets for performances were sold in the taverns about town. Hallam opened a 500-seat theater on Duke of Gloucester Street where the Presbyterian church is today.

But the 1800s were turbulent for Annapolis. As businesses began moving to the new harbor town of Baltimore, Annapolis’ grand social life waned—for 30 years. The Masons first brought back professional theater—in 1873, a new opera house opened on Maryland Avenue at Prince George Street, showcasing Gilbert and Sullivan operettas and vaudeville shows. In 1903, the Woodward and Delaney house on Main Street became a 1000-seat live theater; the architect used elegant eighteenth-century interior elements, including the staircase that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson had trod, in the new refurbished theater. The Evening Capital wrote, “[N] o playhouse in America can outrival this one in history.” When the 300 lights went on, “the effect was magic and the view most beautiful.” Sadly, 15 years later it burned down in a devastating fire. The Hillman Garage now rises where it once stood.

With an opera house and the new most elegant theater in Maryland, Annapolis seemed on its way to a performing arts revival. In 1920, Governor Ritchie cut the ribbon on a new Circle Theater, a vaudeville-style theater on State Circle with dressing rooms, an orchestra pit, red curtains, and 1,800 seats. Popular performers such as Otis Skinner played there. But movie houses began taking the nation by storm, as they were more affordable than live theater. Eventually, the Circle would be purchased by Durkee, the large movie syndicate, and in 1979, after 75 years, it would close its doors.

By the 1950s, Annapolis’ days of grand theaters were over, but live theater continued with community theatrical groups. Colonial Players started in 1949, led by volunteers to celebrate the city’s 300th anniversary. A performance of The Male Animal was staged at the abandoned USO building on St. Mary’s Street. The Players found a permanent home in an old stable and auto shop on East Street, where it performs theater-in-the-round.

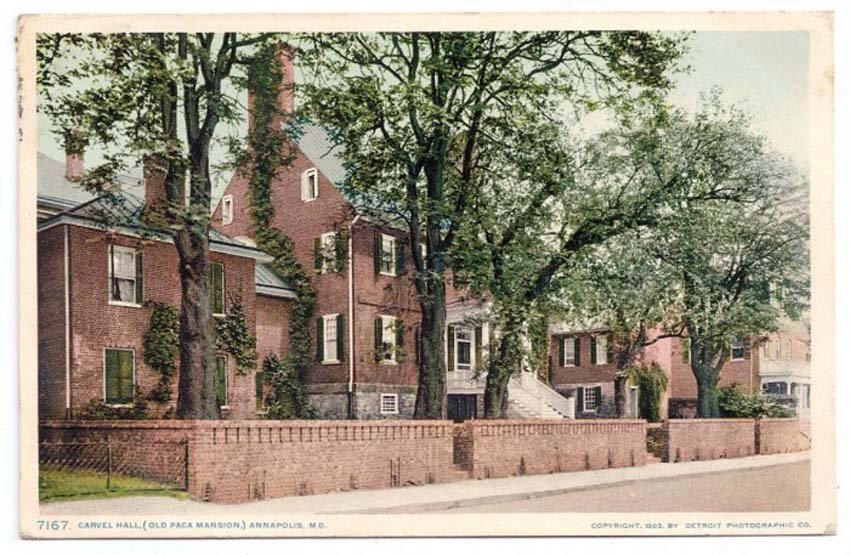

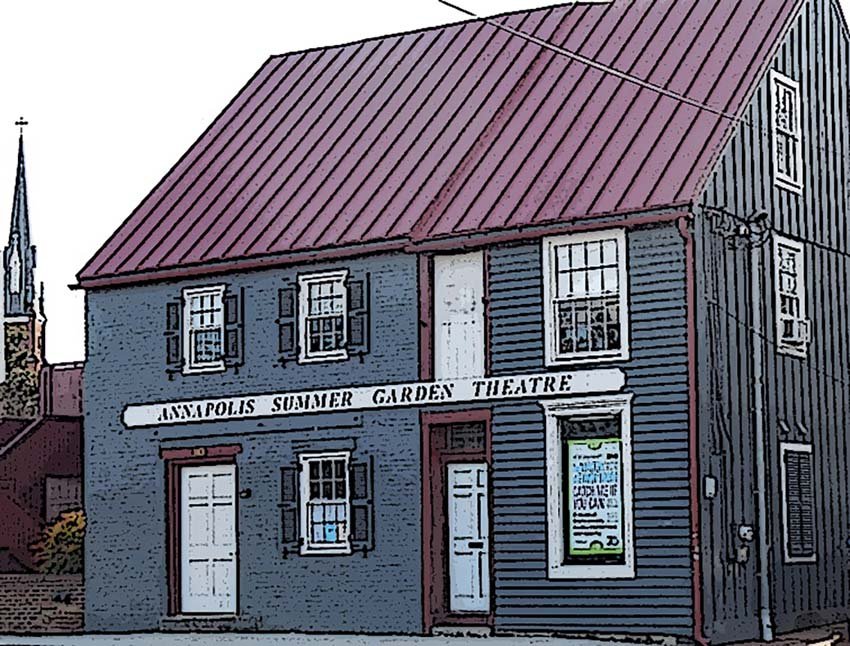

Over 55 years ago, after opening in the gardens at Carvel Hall (now Paca Gardens) with Brigadoon, the Annapolis Summer Garden Theater moved to the old Shaw blacksmith shop on Compromise Street in the industrial waterfront district. The company has performed three Broadway musicals a year since opening as an outdoor, under-the-stars theater.

In 1976, Governor Harry Hughes appointed a commission to bring a performing art center to Annapolis. Commission consultants noted that, despite the “unparalleled richness of its historical and architectural features, the City suffers from a singular poverty in facilities for the performing arts.” It’s recommendation—a 1,500-seat auditorium in a 5,000-seat exhibition hall on the bank of College Creek—never came to fruition, but commission volunteers continued efforts to bring a cultural center to the city. The vacant Annapolis High School building was commissioned to house Maryland Hall as a regional art center, and it opened its doors 45 years ago.

Today, the Classic Theater of Maryland, on West Street, brings professional artists to its stage and cabaret. The Maryland Cultural and Conference Center, now featuring outdoor performances at Park Place, has plans for a state-of-the-art live theater facility.

Athens, with over 700,000 people, currently has 148 stages, the most of any city in the world; Bath remains an architecturally significant spa city of festivals. Annapolis, it’s population at roughly 40,000, has eight stages and is a city of festivals. Theater, with its wit and learning, is alive here. █