+ By Janice Hayes

Happy 200th birthday to Maryland’s most celebrated native son and my personal guide to a greater understanding of the peculiar institution of slavery—and to discovering the founding families of Asbury United Methodist Church on West Street in our historic city of Annapolis.

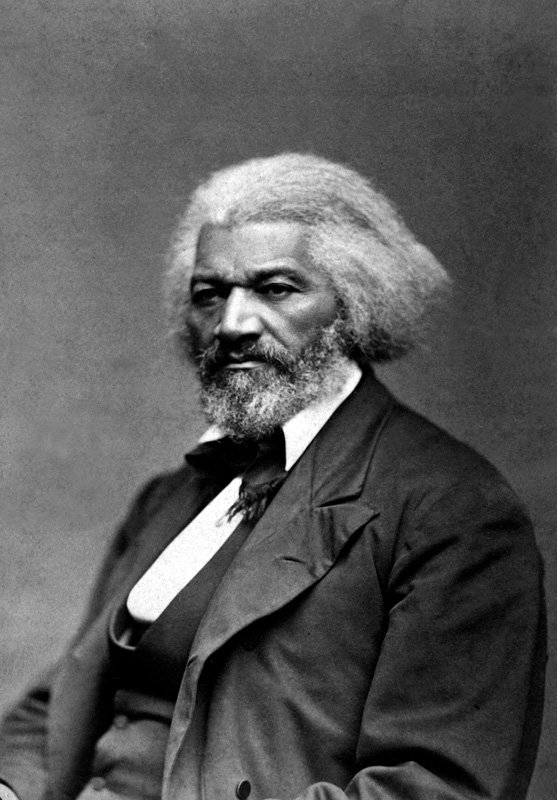

Born into slavery along Tuckahoe Creek on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Frederick Douglass is known to many as the rebellious runaway who championed the abolishment of slavery. Not only did he give thunderous orations against the institution of slavery, but he also had ties to President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War, published the North Star, advocated for women’s rights, and is on record as the most photographed American of the nineteenth century.

In 1818, his birth was recorded in an inventory of Anthony Auld as “Frederick Augustus, son of Harriet Feby.” Listed with scores of other enslaved men, women, and children, Douglass and others were chattel property of Auld, overseer for Colonel Edward Lloyd V, Maryland’s former governor, who possessed the second-largest slave holdings in the entire colony.

In 1818, his birth was recorded in an inventory of Anthony Auld as “Frederick Augustus, son of Harriet Feby.” Listed with scores of other enslaved men, women, and children, Douglass and others were chattel property of Auld, overseer for Colonel Edward Lloyd V, Maryland’s former governor, who possessed the second-largest slave holdings in the entire colony.

Douglass experienced the cruelty of slavery—the need to control and conform vast numbers of human chattel to plantation life—from his owners, carried out by the overseers in their employ. These experiences consistently fueled his hatred and contempt for the institution of slavery, compelling him into a lifetime of resistance.

After his escape from slavery, via Fells Point, Douglass traveled the world and pioneered the abolition of slavery worldwide, growing in prestige at every turn. During the American Civil War, Douglass convinced President Lincoln that the War for the Union could be won if the hand of the black man was released to fight for the freedom. In his words, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship. There is no negro problem. The problem is whether the American people have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own constitution.”

Through Douglass’ efforts, War Department General Order No. 143 was signed into law, creating the United States Colored Troop. “Men of Color, to Arms!” was their battle cry. Records show that 180,000 black men, enslaved and free, were recruited, and after the war, many of them carried out careers in the US military, including at the US Naval Academy. Scores of black and white men from Anne Arundel County served to fight for ending slavery; among these records, I have found two third-great-grandfathers: Nicholas Hopkins and William Booze.

Throughout his life, Douglass recounted life on the plantation of the Lloyds. His earliest memories were of the creolized West Indian family who raised him, the food for the families of the slave owners versus the slaves, the deaths, the floggings, the poverty, and the Lloyds. Among those observances were the Lloyds’ “favored few” who worked in the “Big House,” the masses who worked the fields, the culture of plantation life during slavery, and the differences between the two settings. Douglass wrote of what he witnessed in his autobiography, My Bondage and my Freedom:

Behind the tall-backed and elaborately wrought chairs, stand the servants, men and maidens—fifteen in number—discriminately selected, not only with a view to their industry and faithfulness, but with special regard to their personal appearance, their graceful agility and captivating address . . . These servants constituted a sort of black aristocracy on Col. Lloyd’s plantation. They resembled the field hands in nothing, except in color, and in this they held the advantage of a velvet-like glossiness, rich and beautiful. The hair, too, showed the same advantage . . . so that, in dress, as well as in form and feature, in manner and speech, in tastes and habits, the distance between these favored few, and the sorrow and hunger-smitten multitudes of the quarter and the field, was immense; and this is seldom passed over. (pp. 109–110)

Behind the tall-backed and elaborately wrought chairs, stand the servants, men and maidens—fifteen in number—discriminately selected, not only with a view to their industry and faithfulness, but with special regard to their personal appearance, their graceful agility and captivating address . . . These servants constituted a sort of black aristocracy on Col. Lloyd’s plantation. They resembled the field hands in nothing, except in color, and in this they held the advantage of a velvet-like glossiness, rich and beautiful. The hair, too, showed the same advantage . . . so that, in dress, as well as in form and feature, in manner and speech, in tastes and habits, the distance between these favored few, and the sorrow and hunger-smitten multitudes of the quarter and the field, was immense; and this is seldom passed over. (pp. 109–110)

Here, Douglass also lays the first clue to the founding families of the Asbury Church. The favored few—many of whom were “mullatos” of mixed race—also traveled with the Lloyd family to Maryland Avenue in Annapolis during the meeting of the General Assembly. One of these favored few was Sall Wilks. She lived with her daughters at Maryland Avenue and managed to marry them off to free men of color in Annapolis. Douglass recounts what was said of Wilks’ son William, described as a negro called “Wilkes,” as white as any white man on the plantation, and with a striking resemblance to the Lloyds.

Prompted to do further investigation, “Annapolis Sall,” as she was called, allowed her teenaged daughter Sarah to marry young Reverend Henry Price, son of Smith Price, who gave the land and founded, with others in 1803, the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Annapolis. It is known to us today as Asbury United Methodist Church.

During his final days, Douglass’ son Charles began constructing what was to be his summer home near Walnut Creek. This community, currently known as Highland Beach, was the first incorporated township of African Americans in the nation. A plaque affixed on the home reads, “Here I sit, a Freeman, looking across the Bay to the Eastern Shore where I was born a slave.”

During his final days, Douglass’ son Charles began constructing what was to be his summer home near Walnut Creek. This community, currently known as Highland Beach, was the first incorporated township of African Americans in the nation. A plaque affixed on the home reads, “Here I sit, a Freeman, looking across the Bay to the Eastern Shore where I was born a slave.”

More recently, Maryland Senate President Mike Miller and House Speaker Michael Busch proposed to honor the life and legacy of this esteemed Maryland son with a statue in the State House. The location being considered is the Old House of Delegates Chambers, where Maryland, during its Third Constitutional Convention, abolished slavery, effective November 1, 1864.

Thank you, Frederick Douglass. You still continue to teach. █