+ By Eric Gudas + Photos by Karen Davies

Boredom hung so thick in our fifth-grade classroom, near the end of Ronald Reagan’s first term, that we kept half an ear open for car radios two stories below on Green Street—“Nothing HAPPens on New Year’s Day”—while our teacher, Mrs. C, edified us about . . . I forget what. At the end of the day, my friends and I bolted from school and made our way up Main Street, past the Burger King whose cigarette machine would, just a year later, hold an occult power over me. We often ended up browsing around Lenny’s Junk Shop, located on the first block of West Street by the present-day Rams Head Tavern, near a brick wall where the spray-painted one-liner I’D LIKE YOU BETTER IF WE SLEPT TOGETHER greeted passersby for years and years. Lenny’s truly was a junk shop, insofar as what it sold—like a roomful of pogo sticks—didn’t interest me or lead me so far into the forbidden—like a voluminous collection of Playboys from the 1960s and ’70s—that I’d never have dared to bring it to the counter. The only thing I can definitely remember buying there was a bumper sticker emblazoned with HEY KIDS, LET’S GO TO LENNY’S JUNK SHOP!

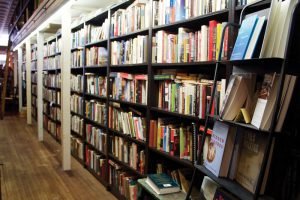

You can’t go to any of the places where I loitered back in the ’80s, like Lenny’s or Oceans II Records on Main Street, in which—and presumably at different ages—I bought cassettes of ABBA’s Super Trouper and (on the day it came out!!) Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs. But mostly I remember the bookstores in and around downtown, so many I can’t recall all their names; although there couldn’t have been more than five or six between 1983 and 1989, the mythic era of my adolescence. Even that number of bookstores, in a town the size of Annapolis, seems incredible to me now that books themselves have become an increasingly esoteric throwback to a pre-Internet and pre-iPhone era. No doubt print was, even then, on its way out, because I loved those bookstores for their homegrown, slightly ramshackle atmosphere.

You can’t go to any of the places where I loitered back in the ’80s, like Lenny’s or Oceans II Records on Main Street, in which—and presumably at different ages—I bought cassettes of ABBA’s Super Trouper and (on the day it came out!!) Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs. But mostly I remember the bookstores in and around downtown, so many I can’t recall all their names; although there couldn’t have been more than five or six between 1983 and 1989, the mythic era of my adolescence. Even that number of bookstores, in a town the size of Annapolis, seems incredible to me now that books themselves have become an increasingly esoteric throwback to a pre-Internet and pre-iPhone era. No doubt print was, even then, on its way out, because I loved those bookstores for their homegrown, slightly ramshackle atmosphere.

A benign seediness permeated West Street Books, across the street from Lenny’s, which seemed to extend for miles—one dusty, dimly-lit room opening into another, until some rickety stairs led up to even more dilapidated, book-glutted chambers. I remember books about UFOs, plenty of Kurt Vonnegut paperbacks—including Mother Night, which my sixth-grade teacher, Ms. L, found in my desk and then forbade me, moralistically, ever to bring back to school—and Diane Wakosi’s Motorcycle Betrayal Poems, whose 1970s-era cover I recall better than its contents. How did such a store’s owners pay the rent? Certainly they didn’t make much money from twelve-year-old me, who was more likely to hunch over a wooden step stool, furtively rereading The Godfather’s salacious opening chapter (“She felt Sonny’s mouth on hers, his lips tasting of burnt tobacco, bitter”), than to buy anything except an occasional 50¢ paperback or the BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU poster that adorned my bedroom until I left for college.

Downtown proper had more highbrow bookstores, including The Haunted Bookshop, whose owner’s black cat famously lolled in the window facing Main Street. I’m embarrassed to say I spent just as much time, if not more, across the street at Crown Books, which was widely reviled when it opened for insinuating a chain-store ethos—and pricing—into downtown. I secretively loved the store for its wealth of mass-market paperbacks, many of which I wouldn’t have been allowed to read at home. After school and on weekends, I pored over the excruciatingly awkward first-sex scenes in Judy Blume’s Forever and the giggle-inducing gore-arias of Stephen King’s The Stand, the bulk of whose 900+ pages I read right there in the store.

Downtown proper had more highbrow bookstores, including The Haunted Bookshop, whose owner’s black cat famously lolled in the window facing Main Street. I’m embarrassed to say I spent just as much time, if not more, across the street at Crown Books, which was widely reviled when it opened for insinuating a chain-store ethos—and pricing—into downtown. I secretively loved the store for its wealth of mass-market paperbacks, many of which I wouldn’t have been allowed to read at home. After school and on weekends, I pored over the excruciatingly awkward first-sex scenes in Judy Blume’s Forever and the giggle-inducing gore-arias of Stephen King’s The Stand, the bulk of whose 900+ pages I read right there in the store.

In Charing Cross, at the top of Maryland Avenue, a slightly officious man (the proprietor?) perched behind the counter, stroking his Van Dyke-ish beard and guarding the microfiche rolls of Books in Print. I’m sorry if I do this gentleman an injustice by thus describing him; in my adolescence, I was hyper-conscious of authority figures and always inwardly ready to mock them. Yet he let my friend and me put our photocopied poetry magazine, Love Decagon, out for sale. (No one bought a copy, of course.) He really did act as a gatekeeper, since in those pre-Internet days the arcane volumes of poetry and literary fiction I was so hot to obtain were only available by special order. I’m afraid my jerk-hood increased with my literary sophistication, since sometimes I ordered books on the basis of their titles only—Bela Lugosi’s White Christmas comes to mind—and then declined to buy them, leaving him (I understood years later) on the hook with the distributor.

I know when Larry Levis’ Winter Stars—which I ordered and bought—arrived, because I wrote the date on the book’s inside flap: August 8, 1988. Those poems, with their evocations of a childhood in California’s Central Valley, spoke as directly to my teenaged ennui as Dylan’s “Visions of Johanna.” Since I encountered it at fifteen, Levis’ “The Poet at Seventeen” has been one of my all-time favorites:

I hated high school then, & on weekends drove

A tractor through the widowed fields. It was so boring

I memorized poems above the engine’s monotone.

Sometimes whole days slipped past without my noticing . . .

In 1988, I, too, was bored more often than not—bored of my hometown’s suffocating quaintness; bored of killing time at Annapolis Senior; bored of sailboats, sailboats, sailboats; bored of being myself—whoever that was. Books, and the worlds they gave me access to, became my ticket out of town; but without those long-gone bookstores I wouldn’t have found as many of them (books and worlds).

In 1988, I, too, was bored more often than not—bored of my hometown’s suffocating quaintness; bored of killing time at Annapolis Senior; bored of sailboats, sailboats, sailboats; bored of being myself—whoever that was. Books, and the worlds they gave me access to, became my ticket out of town; but without those long-gone bookstores I wouldn’t have found as many of them (books and worlds).

I mourn the loss of such spaces, not just in Annapolis but also in my adopted home of California, where iconic independent bookstores like Santa Monica’s Midnight Special and Cody’s in Berkeley have closed their doors since I moved out here twenty years ago. Many young writers I know, though, seem to have found their own ways into literature—not in bookstores but via the Internet. A student in my writing workshop recently raved about discovering recordings of poets like Langston Hughes on Spotify. Who knew? So I don’t mean to cling preciously to my own, old-school way of encountering the Word…. Yet I do cling to it, and to those hours I spent haunting the shelves of book-clogged rooms that felt like, and were, my other homes. To the owners and shift-workers of those sanctuaries where this know-it-all teenager treated the inventory like a library’s stacks and, every once in a while, actually bought a book: I’m sorry I took you for granted. █