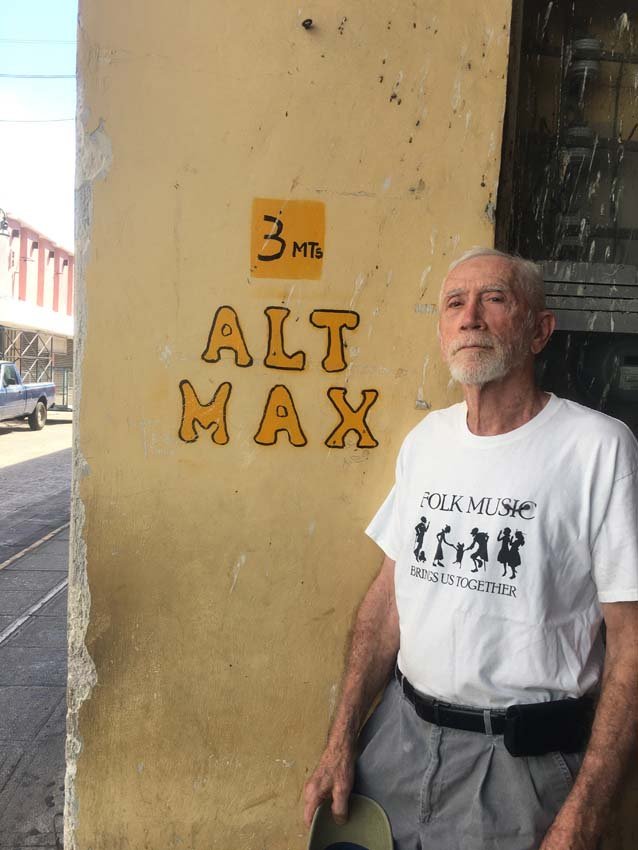

+ By Rahsaan “Wordslave” Eldridge + Photos by Gregg Patrick Boersma

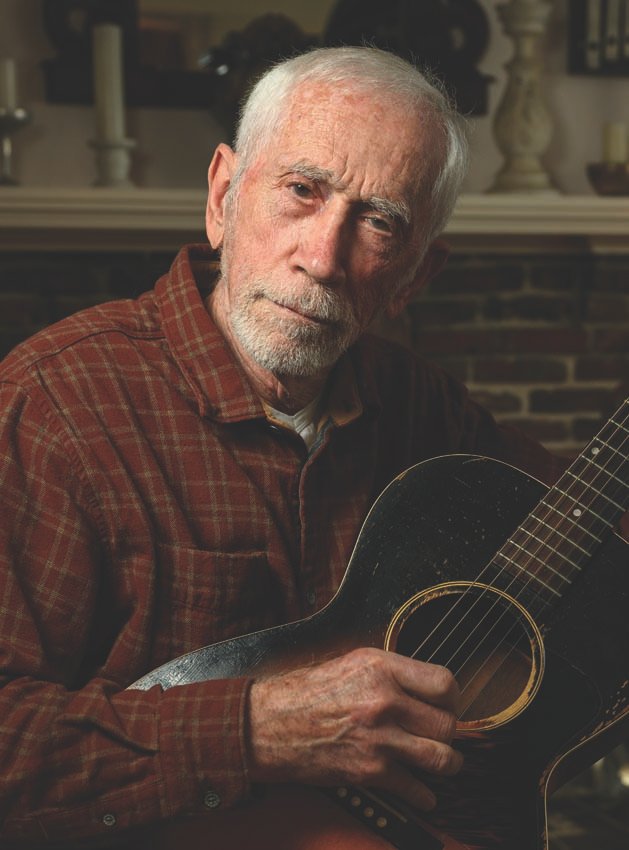

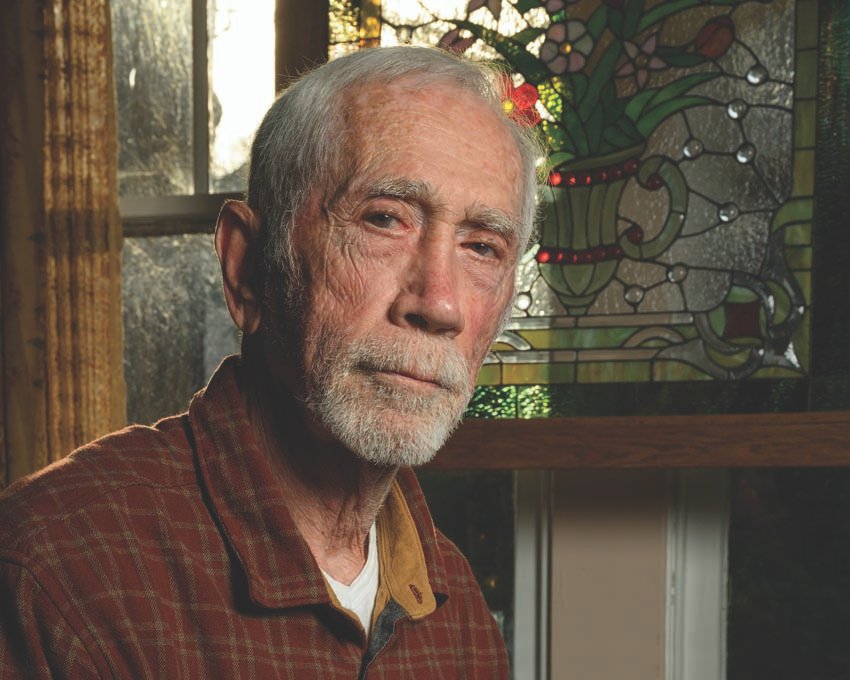

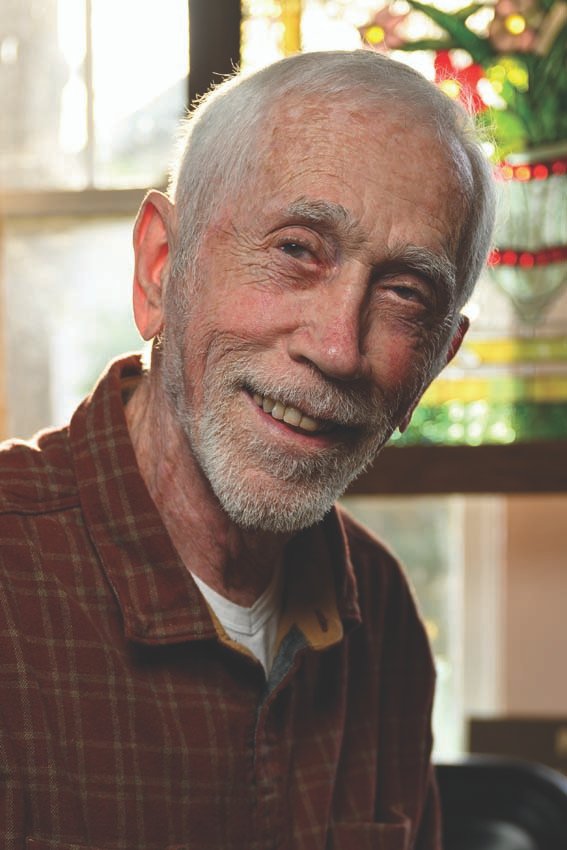

Max Ochs is a gem. He’s a musician, poet, and teacher with some keen insights on the ways of the world and spirituality. He’s humble, considering his rich legacy as an ambassador for music, peace, and humanity.

His family moved to Annapolis in 1945, when Ochs was four years old. His father had just been discharged from the army at the end of World War II. Ochs is now 83, “a big number for an age” he says, and he expresses overwhelming gratitude for his journey. “I am blessed I’ve been allowed to live this long and allowed to have so much music and fun, and meet so many incredible people, and play with so many wonderful musicians.”

Ochs was always a diligent student of music, and it’s evident in his versatility as an artist who plays multiple styles and several instruments. His musical influences are vast. He has fond memories of going to Annapolis’ famed Carr’s Beach and Sparrows Beach as a teenager to see Bo Diddley, Ray Charles, Jerry Butler, Otis Redding, and The Drifters. He also grew up listening to Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin, and other classical music that his father would play at home. To Ochs, they were just several rivers emptying into the same bay—all connected.

He credits the development of his musical ear to playing violin beginning at age 11. He says that because it doesn’t have frets, it made it easier for him to later transition to guitar. He also studied drums for a while, ironically leading to a chance meeting between him and his first guitar teacher.

In high school, he wasn’t doing well in math, and his father was worried that he wouldn’t get into college, so he was made to see a tutor at the Naval Academy. However, instead of going there, Ochs would detour to Severna Park and go to drum lessons. One day, on his way home, he saw a someone hitchhiking on Ritchie Highway. Ochs picked the man up because it was raining and he didn’t want him getting wet. The man’s name was Harry Banks, and he was to become an early teacher for Ochs, one of many impactful connections he’d make over the years. Through conversation, Ochs learned that Banks played guitar. Ochs had recently acquired a guitar and told Banks that he wanted to learn, so instead of taking Banks to his initial destination, he brought him home, where Banks tuned Ochs’s guitar to open tuning and ran a kitchen knife over the strings while he played. At that moment, Ochs fell in love with what he calls the “fluid-liquid sound” of slide guitar, a sound and technique that he still uses in his playing.

Ochs is known for frequenting hootenannies, gatherings where singers and guitarists play blues and folk music, often soliciting audience participation. He loves to have people sing along with him, which is indicative of his general philosophy that there are two approaches to music: competition and community. Competition doesn’t interest him much; he’d much rather collaborate, and he attributes his preference for community as partly the reason for his modest commercial success.

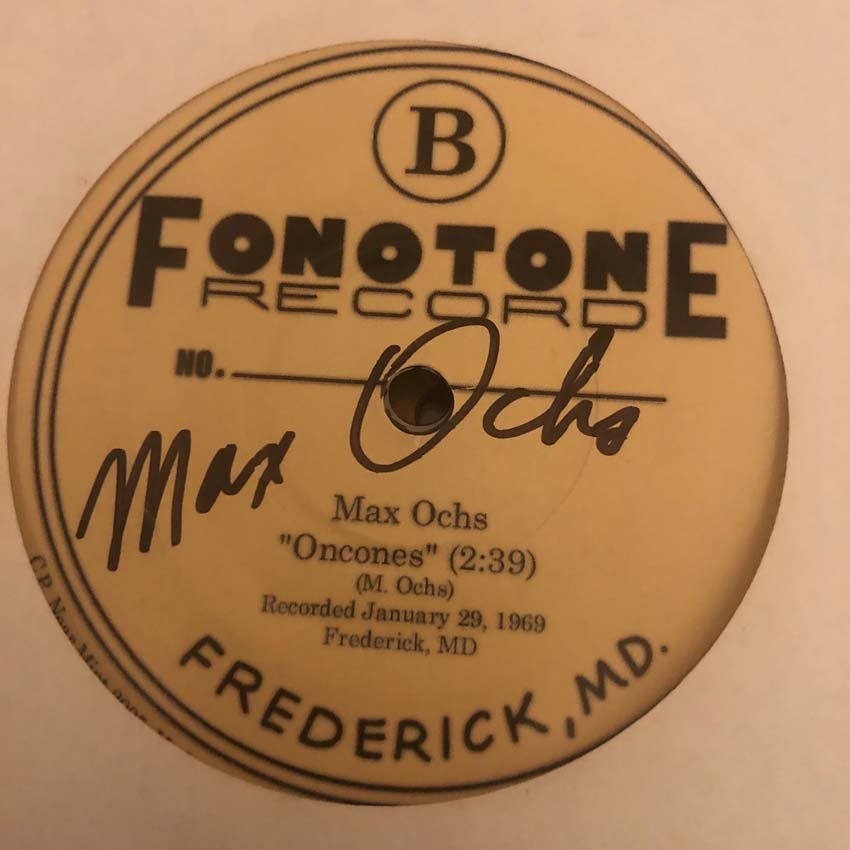

During the folk music movement of the 1960s, he was in the mix at coffee houses and hootenannies and more than crossed paths with artists in the forefront of that era. Ochs recalls a performance in New York where Bob Dylan was in the audience and came onstage to sit in for a version of “Oxford Town.” Other collaborations included Robbie Basho and John Fahey, who is often credited for introducing a genre called American Primitive, a style of folk music characterized by its unique fingerstyle picking—a style that Ochs gravitated toward. He met Fahey while a college student at the University of Maryland and recorded on Fahey’s Takoma Records label, named after Takoma Park, where Fahey grew up.

In 1962, Ochs moved to New York and joined the raga-rock band Seventh Suns. Lead singer Buzzy Linhart made a lasting impression on Ochs—some of Linhart’s vocal choices reminded him of Ray Charles.

He’s also been tied to a collective known unofficially at the time as the Blues Mafia. Ochs is not fond of the name but acknowledges that the group of musicians had a deep appreciation for blues and folk music. Their aim was to uphold and preserve the standards of the music that so heavily influenced them. One of the musicians they respected and whose music they would study and cover was blues legend Mississippi John Hurt. “I’d say that I’ve met maybe four or five great men,” says Ochs, “and Mississippi John Hurt was one of them.”

He feels fortunate to have met and befriended Hurt, who spent time at Ochs’ New York apartment, even staying there for a brief stint. Ochs would host hootenannies at his home that often ended with him and Hurt sharing music one-on-one. One night, after hearing Ochs play, Hurt questioned him about the meaning of a lyric. When Ochs couldn’t answer, Hurt offered his explanation about what he thought it meant. At the time, Ochs considered himself an atheist, but Hurt’s response shifted his perspective on God and soul.

Beyond being a musician, Ochs is an underrated poet, and his poetry is schemed beautifully with rhythm and rhyme. Ochs writes about his time with Hurt in his poetry book With Mississippi John Hurt

and one time Max was

singing along about

the soul not thinking

of the words at all

but only the throes

and thrum of chords

and John asked him

what he meant by soul

and Max couldn’t say

a single word

and John said

soul meant

the spirit the body

the personality

everything the entire man

the whole man

that was soul

As a teenager, he was inspired by Beat writers Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, and Kerouac’s On the Road made him pick up the pen. His book of poetry titled Just Caws is dedicated to fellow friends and poets as well as his wife, Suzanne. The book title is a testament to his clever wordplay; a double entendre referring to the sound made by crows (Ochs has an affinity for birds and their musicality) and a nod to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s quote “I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” The collection of 63 poems covers a wide range of subjects—quite apropos for the multifaceted Ochs.

Ochs refers to himself as a lover of sound: the slide guitar, the singing of birds, the melody in speech patterns, the connection of words and syllables in lyrics and poetry. The connecting thread in all of his creative endeavors is his attention to the human condition.

In 1970, Ochs earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Maryland, and in 1991, he received a master of arts degree from the School of Liberal Education at St. John’s College. In 1995, he became co-executive director and schools program manager of the Anne Arundel Conflict Resolution Center, an organization that works to peacefully resolve conflict between residents of Anne Arundel County. He’s taught history and literacy and trained other mediators. He’s received countless citations and recognition, including a Certificate of Congressional Recognition from the City of Annapolis for his contributions to the fight for justice and equality. He’s been arrested for protesting the Vietnam War. All this while sliding and fingerpicking with some of the most influential American musicians. All this while leading sing-alongs at hootenannies and coffeehouses such as 333 Coffeehouse, which he founded in 1992 at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Annapolis, the church he still attends.

Ochs thrives on connection and community. He believes in echad, the Hebrew word for one, which he believes to be the origin of the word God. One of his favorite worship songs to lead is “When All Thy Names Are One,” by Bob Zentz. Hierarchy and division are unnecessary; he doesn’t believe in best or better.

Over 83 years, Ochs has abided by many titles—musician, student, teacher, poet, and activist, to name a few. None are more than any of the others, and all are for the same greater good. All of his names are, indeed, one.

For more information, visit maxochs.com.