+ By MacDuff Perkins + Photos by Nicole Caracia

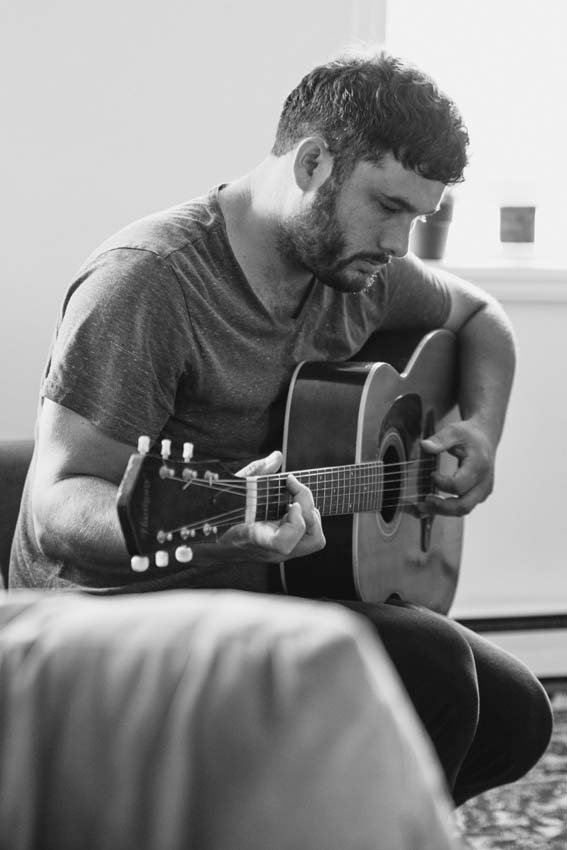

It’s a Saturday afternoon in Eastport, and Alexander Peters looks tired. He has a few days’ worth of scruff on his jawline, and his shoulders hunch as he leans over his guitar to tune it to his bandmate’s. Violinist Crosby Cofod is wearing a fanny pack, drummer Josh Bolyard ties a bandana around his head like a 1980s aerobics instructor. The sun inches a little higher in the sky, and the audience maneuvers around the lawn, seeking shade.

A southerly breeze skirts across the creek just as Bolyard’s bass drum kicks, and Peters is at once alive. He’s vibrating; his hands are a blur, and his voice is vacillating between a falsetto hum and raspy growl. The music, he says, is “ bluegrass with a pop hook.” He’s singing about gardening, but he’s also singing about the meaning of life. Suddenly, a harmonica appears, and Peters is a wall of eclectic sound. On the lawn, feet are bare, and noses are burnt, but as the music kicks up, arms link and bodies begin to spin like children.

A few days later, Peters is drinking black coffee in the back of a downtown Annapolis café. It’s a sacred day off for him—each week, he works 30 busy hours at a day job and then gigs three to four nights, clocking in at 6 a.m. and clocking out after midnight.

That explains the scruff.

“When I have down time, I appreciate it,” says Peters. He sees fatigue as a sign that he’s doing something right. “Some people play better on their tenth night, because your body understands overtime,” he says. “People push harder in that moment. For me, tiredness is like a rooster calling, saying it’s time to sprint.” The symbol of a rooster resonates strongly for him.

With a catalog of songs deeply influenced by Americana, Peters’ music is a running commentary on traditional American values—a hearty work ethic being primary among them. He celebrates the freedom found in a backyard, the romantic adventure of an open road, and the fact that often one’s quality of life is measured in sweat.

On his song “American Dreamer,” he croons, “Gonna dig a hole where your heart can go, put it in the ground and let the thing grow.” The lyrics come directly from his commitment to playing music on top of the nine-to-five grind. “There’s something about working hard and coming home at the end of a long day. If you can still have your dream when you’re working that hard, you can do it. But if you let go of the dream, it can kill you,” warns Peters.

He was lucky enough to find his dream during his childhood. Growing up in Mayo, his home was filled with musical instruments for Peters and his sister to enjoy without pressure. “Putting your kid in piano lessons at five can backfire,” he says knowingly. “So instead, we had a big tub full of things you’d have in a fifth-grade music class. We had lots of shakers.” His father is a talented guitarist who never pressed his son to study music. Peters’ mother educated both children in music appreciation by keeping a constant soundtrack of all 1960s genres playing in the home.

As an early teen, Peters had a friend who could play the guitar. “I thought he was so cool because he could play Nirvana and Metallica, so I asked my dad to teach me,” he says. “Pretty soon, I was playing the guitar nonstop. It was a healthy obsession.” Over time, he began to realize that his calling wasn’t to be the world’s greatest guitar player. “Lyrics were starting to stand out more,” he says. “I was inspired by Bright Eyes and Bob Dylan. I was playing in the rock band Contra with loud guitar and feedback, but I’d always had this other side that was acoustic, a side that had a knack for lyrics. I realized I am more of a writer than a guitarist.”

As a songwriter, Peters is methodical to the point of obsession. He might start with a hum or a word tripping through his brain on repeat. A phrase might develop, a few words strung together in a shadowy mumble, syllables slowly taking shape without meaning. But soon, there might be one line, a phrase about something. “If there’s enough magic in that one line, I can write a second line. I’ll start singing that again from the beginning, and those ten seconds can let me flow into the next line,” he says. “If I can do that, I’ll keep moving forward. I’ll find a chorus. I might write a quarter of a song before I know what I’m talking about. And after 100 times, or a few months, I may have a song.”

This process has resulted in three albums and one EP over the last 11 years, most written on the couch next to his patient dog, Huckleberry. Through each, Peters observes life through the lens of a millennial Woody Guthrie, navigating a world that is changing at a pace few can keep up with. Digging into the singer-songwriter and folk genres, Peters explores the nuance of his American experience with the emotional cognizance of his generation.

“If I can use music as a tool to reach people, hope and positivity is what I want to give them,” he says. “I don’t have a podium, but I have a mic. When I’m performing, I try to connect with people. If I can take a song and let them all escape their problems for three minutes, that’s pretty magical.”

There is a significant difference between connecting with a live audience and connecting online with the TikTok generation. Hence Peters is like a chameleon, allowing the treatment of his music to change and adapt between the studio, stage, radio, and internet to reach more people.

“I’ll listen to pop music and look for the little tricks that producers use,” he says—a pause, a bass drop out, a baby’s giggle. “These are little tricks that the ears love. Then, when I’m in the studio, I’ll try to incorporate those things into my own songs.” When he plays live, they must come from him directly. With an expansive vocal range, he can flip from the deep bass growl to a falsetto vibrato with ease. “Singing really loudly isn’t the way to get a room’s attention. Right now, I’m trying to make yodeling cool again.”

Peters raises his hand to his head, exposing a tattoo of a rooster on his upper arm. “I’m excited to be alive,” he says. “And if I’m not, I’m going to teach myself how to be. If I’m feeling down one day, I still have to get up in the morning, push forward. That’s the rooster.”

Peters finishes the last dregs of his coffee and slides his chair back from the table. He has the afternoon to hang out with Huckleberry, spin some vinyl, and get a haircut. He might try to check out a friend’s show later in the evening, but he plans on going to bed early. Because everyone knows you can’t sneak the sunrise past the rooster. █

For more information, visit

alexanderpetersmusic.com.