+ By Leigh Glenn + Photos by Larry Melton

Every medium of expression is about capturing light—the arch of a ballerina’s foot en pointe, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, a Bach prelude. We swim in an ocean of light, yet we are like fish that don’t know water. This makes capturing light a challenge, especially with visual images. Overemphasizing image, as our culture tends to do, makes it difficult to see. And when we seek it out, we often have tunnel vision. For photographer Dick Bond, a camera gives him sight. As such, he has spent his life learning how to see.

When it comes to photography and visual images, Dick Bond may be Annapolis’ best kept secret. Former photography students from Anne Arundel Community College and Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts know him, as do his small group of followers, whom he calls the Luddites. He is also a familiar face to some of the old-timers at the Naval Academy Museum, the City of Baltimore, and the State of Maryland, where he has photographed for various projects.

When it comes to photography and visual images, Dick Bond may be Annapolis’ best kept secret. Former photography students from Anne Arundel Community College and Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts know him, as do his small group of followers, whom he calls the Luddites. He is also a familiar face to some of the old-timers at the Naval Academy Museum, the City of Baltimore, and the State of Maryland, where he has photographed for various projects.

Born in Nova Scotia 73 years ago, Bond left the Maritimes at age six, when his father’s work brought the family to Philadelphia’s Welsh Valley. Growing up, Bond often traveled into the city to explore the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Franklin Institute, a science museum, became his home away from home.

In 1960, Bond came to Annapolis to attend St. John’s College. One day, a friend borrowed Bond’s camera to take pictures at the National Zoo, and Bond was struck by the images. He then thought he should be the one taking pictures. When he did, he made what he considered completely indiscriminate, mediocre photographs that lacked content and composition.

He developed his photographs in a small basement darkroom at a friend’s house outside of Washington, DC. His time behind the camera and in the darkroom allowed him to make a number of amateur mistakes, which informed one of the first lessons he would later share with students: “In photography, there are an infinite number of mistakes you can make; endeavor to make them only once.”

St. John’s College did not provide Bond with enough course work in mathematics, so in 1962, after marrying his girlfriend, Meg, he enrolled at the University of California in Berkeley. He soon realized that mathematics did not provide him with the clarity he sought. His thesis, on relativity and black holes, earned him a recommendation and acceptance into the astrophysics program at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. He and Meg moved to the East Coast in 1964.

While studying at Hopkins, he served as a teaching assistant. The college had rules governing speech both on and off-campus, and faculty and staff who attended anti-war demonstrations were penalized. Despite being near the end of his doctoral course work, Bond quit school. He fell back on his avocation, photography, and began taking on assignments and instructing at Anne Arundel Community College.

While studying at Hopkins, he served as a teaching assistant. The college had rules governing speech both on and off-campus, and faculty and staff who attended anti-war demonstrations were penalized. Despite being near the end of his doctoral course work, Bond quit school. He fell back on his avocation, photography, and began taking on assignments and instructing at Anne Arundel Community College.

But Bond’s obsession was not with photography—it was with seeing.

He recalls being assigned to document the remaking of Baltimore Harbor and hating the idea of photographing junk. To his surprise, he fell in love with machinery. One machine, a steam-powered Vulcan pile driver, mesmerized him. “Every time it dropped, a cloud of the whitest vapor you’ve ever seen in your life puffed up. That blue blue sky and the white white vapor . . . I have never really gotten over it.”

For five years, Bond was the official photographer for the US Naval Academy Museum. One of his projects—photographing the interiors of model ships—allowed for the study of shipbuilding history. He put an endoscope and a fiber optic cable through the miniature gun ports of a 1710 British model ship and painted the interior with light for 20-minute exposures. This offered an intimate look at details that no one would have otherwise seen.

Bond once believed that seeing was about getting closer and closer to a subject. In that pursuit, he amassed longer and longer lenses. But this turned out to be another mistake. “[At first,] I saw photography as a way to revere that which was hidden from our normal senses,” Bond says, but then he realized differently. “The things we fail to see are not hidden deeply—they’re right on the surface, and we still ignore them.”

Once he learned this, he gradually sold off all of his long lenses.

Seeing leads back to light. Over the years that he taught photography, Bond had a singular initial assignment for students: photograph the same object in different settings, over and over. Students learned about light—what reflects it, what diminishes it, and what it looks like against all types of backgrounds.

Bond says that, of the more than 20,000 images that he reviewed from that assignment, no two were alike. This illustrates another key aspect of Bond’s teaching—photographs serve either as mirrors for those who make them, or as windows that show the world as it is.

He tried to instill in his students the importance of acting as mirrors with respect to their subjects. Doing so is key to making photographs that delve deeper than simply documenting or capturing a moment in time. “Your attention is worthy of your subject,” he says, “and paying attention is very much harder than it appears on the surface.”

At Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, one student set up his camera just slightly off the trail, waiting for the moment when the sun would be just right. People walking the trail began silently congregating around him. When the moment came, he pulled the release, taking the photograph, and the crowd started clapping. Bond laughs with joy, on the verge of tears, as he relates this story.

At Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, one student set up his camera just slightly off the trail, waiting for the moment when the sun would be just right. People walking the trail began silently congregating around him. When the moment came, he pulled the release, taking the photograph, and the crowd started clapping. Bond laughs with joy, on the verge of tears, as he relates this story.

In photography, there is always a conflict between process and product. If the emphasis is on product, then attention is not paid to the process. Bond says that emphasis on process is evident in the images of great photographer-craftsmen such as Ansel Adams, Frederick H. Evans, and André Kertész—regardless of their subjects, these photographers were all paying attention.

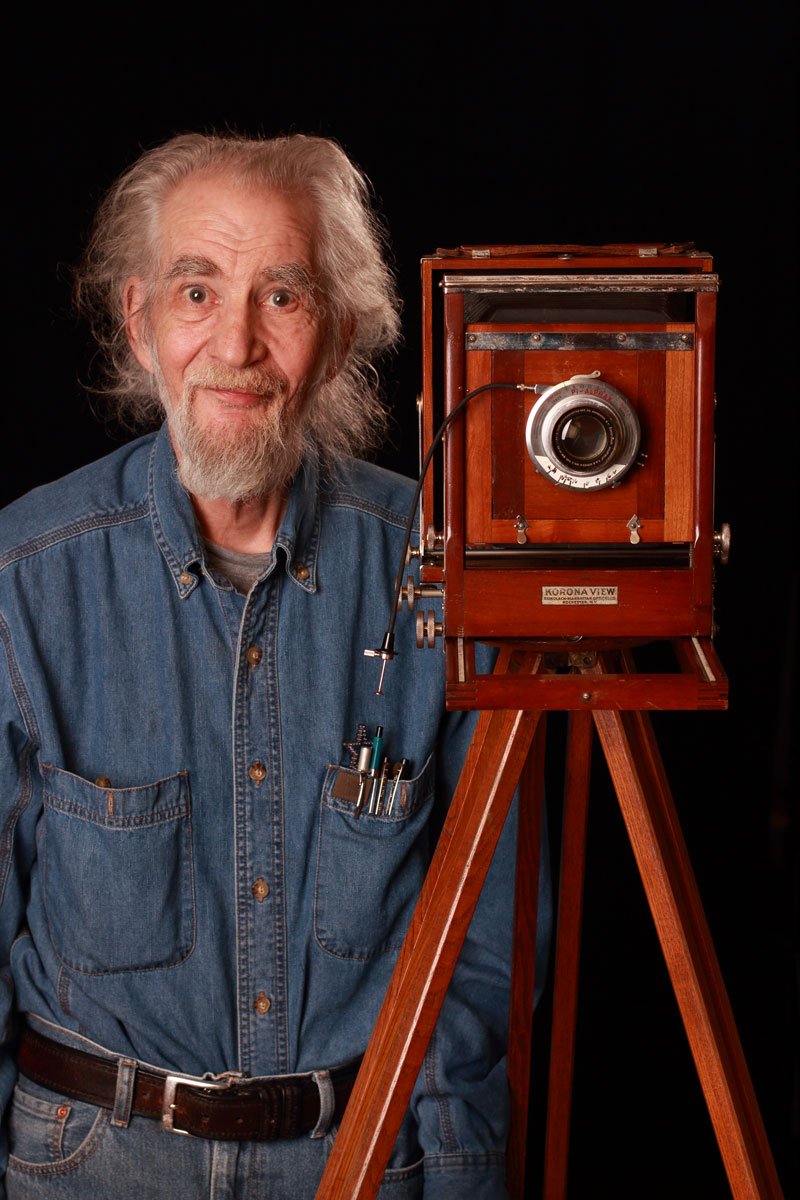

Bond now uses the same type of camera that Kertész used, an 1895 Korona Viewfinder that once belonged to a student’s grandfather. It took Bond about three months to restore it. He appreciated the Hungarian photographer’s clarity of vision, which he recognized some years ago at a retrospective at the National Gallery of Art. “I was blown away by what he was constrained to do by his camera.” That helped him feel a bit better when he could not get the film to print at a larger size. He brings out a book of Kertész’s work, where many of the early photos measure only one and one-half by two inches. “I was shocked,” he says.

Before his stroke nearly one-and-a-half years ago, Bond used to haul all 32 pounds of tripod and camera to Bacon Ridge Natural Area, near Crownsville, to go on what he calls meditative walks with photographic interludes. He collected those photographs into 17 volumes, which he named À la recherché d’images perdu, a riff on Marcel Proust’s À la recherché du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time).

Using the Korona has opened up another world for Bond to explore. “I never learned so much,” he says, “it does give the word ‘deliberation’ a whole new meaning. This format is so big, so clumsy, and so slow, that I actually get the feeling of the light exposing the film.”

And the results?

The lush black-and-white images would be impossible to capture with the human eye. We just don’t see that way—every leaf of skunk cabbage sharp, the lights and shadows on and among them just as sharp, the trees in the background clear. You could only have a richer experience by being with Bond when he’s making these images. Bond reveres the woods and their infinite possibilities. “If I impart to my viewers some fraction of the magic I encounter in the woods,” he says, then he has done his job.

Over its nearly 200-year history, photography has had its share of critics, including those who maintain that it has detracted from our ability to really see a particular thing. Bond is not one of those people. “It’s allowed me to see better,” he says. Moreover, it has enlarged his imagination. “That is a gift beyond price.” █