+ By Leah Weiss + Photos by Paul W. Gillespie

“It’s odd, bringing people into my dirty basement,” says Paul Gillespie with a slight smile and a nervous laugh. More cluttered than dirty, the area provides a visual collage. An abandoned woodworking setup dominates the space. Boxes and wood abound. A figurehead from a ship’s bow hangs on the far wall. A dryer hums, rotating its load. Then there’s the tiny room with lights on boom stands, handcrafted backdrops, and memorabilia from the Capital Gazette hanging on the back wall—the photography studio where Gillespie dreams big. “It’s very tight,” he says, moving equipment just to turn on a light. “It’s like a guerilla-style photography, just doing what you gotta do to get the pictures.”

A photojournalist from New Jersey who’s now in his late 40s, Gillespie has been a staff photographer at the Capital Gazette for 18 years. The pictures to which he’s referring, however, are not work related. He’s been spending most of his free time this year creating new black-and-white portraiture photography that culminated in a project titled “Journalists Matter: Faces of the Capital Gazette.” It’s also been his path towards healing from a series of traumas he’s recently experienced.

Gillespie is well known professionally for his sports photography and personally for his humor. “When people first meet me, they might think I’m a little bit surly, maybe. Once people get to know me, they see I’m goofy. I say crazy stuff, and my wife writes about it [on Facebook].” After he begins speaking, any outer brashness vanishes, and his straightforward, open manner reveals a core of empathy and thoughtfulness.

Bill Horin, founder and creative director of ArtC in Linwood, New Jersey, was Gillespie’s first photography instructor at Atlantic Cape Community College and hired him as his assistant, giving the then-24-year-old his first photography job. “He is one of the most reliable people I’ve ever met,” says Horin. “He was delivering pizza at night, and it didn’t matter what time he finished work. If he got done at 2 a.m. and I had a 7 a.m. shoot, he was there, waiting for me. He had a lot of energy for doing this kind of work.”

Over the years, Horin mentored Gillespie as he committed to the craft and blossomed as a photographer. “We developed a friendship after working together, and we’ve stayed friends ever since,” says Horin. “He’s been there for me a lot. There’s only a handful [of people] you meet in your life like Paul.”

In 2014, Gillespie’s mother passed away after battling cancer (his father passed away some years before). A few years after, his brother, his only sibling, who lived in the basement room in Gillespie’s modest Brooklyn Park home, died suddenly. Fourteen months later, while Gillespie was working at his desk in the Capital Gazette offices in Annapolis, a gunman opened fire on everyone. Five of his colleagues were killed.

“It didn’t start off to be a project. It started off as something for me to do, in my down time. I was having problems with depression and PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and anxiety,” he explains. After the incident, he only had energy to do his job; otherwise, he felt drained, withdrawn, and extremely anxious. “I was sitting in here, just going on Facebook. I wasn’t doing anything. My head would get swirly, I’d have this chest feeling. My body would twitch, sometimes.”

Charlotte Byrd, a local psychotherapist specializing in trauma, sheds light on Gillespie’s symptoms. “An animal surviving a life-threatening event will literally just shake it off. It will shake and jerk until the energy of surviving that traumatic event is dispelled,” she says. But human beings are more complicated—we tend to freeze up in the face of trauma while cortisol and other stress chemicals release into our brains. “That’s when we get severe anxiety and hypervigilance,” she says. “And we start developing a strong neural network of negative beliefs, about the world and about ourselves.”

This past January, Horin called Gillespie. “I said, ‘Paul, I just watched this documentary on this photographer’s style, it’s really cool. I think you’ll get a kick out of it.’” The film, part of a Netflix series titled Abstract: The Art of Design, featured Platon, a British photographer known for his highly contrasted black-and-white portraits. “Next thing I know,” says Horin, “he’s starting to send me pictures that he did, and I’m like, holy man, these are really, in my opinion, his best work.”

Platon’s work resonated strongly with Gillespie, bringing up excitement and motivation, feelings he had not experienced for a while. “The black-and-white images spoke to me. The contrast was amazing. I said to myself, ‘I want to make pictures like that!’” Once the idea took hold, Gillespie got to work. He cleared out his brother’s things from the basement room—not an easy feat emotionally—and turned it into his studio. He brought out his old studio lights, supplemented them with a newly purchased used light, and bought supplies from the Dollar Store.

The small studio, with its seven-foot-high ceiling, presented technical difficulties, limiting the type of pictures Gillespie could take. Subjects had to sit rather than stand, and he couldn’t light his subjects and use backdrops in the ways that he wanted to. He improvised, deviating from Platon’s specifications, making the style and approach his own.

Without any fixed plan, Gillespie first took pictures of a friend and himself. He converted the images to black and white, cropped them, and then spent hours toning them to look exactly as he envisioned. He then began photographing his other friends—his colleagues at the Capital Gazette, starting with Selene San Felice. The project took form organically, and “Journalists Matter” came to the fore as its focus. “I want to show people who you are,” he told his colleague-subjects. He asked them to bring whatever they wanted to their sessions. In the photographs, one sees items of significance that connect to the incident and its aftermath—pictures of lost loved ones, a cell phone, a reporter’s notebook, an article of clothing, the newspaper.

The time that Gillespie spent with each person before clicking the shutter is apparent in the pictures. They convey a range of emotions, as if capturing each person’s essence and grief, and tell a story. The intimacy is palpable because of who Gillespie is, as a person, friend, survivor, and photographer. “I am very careful that I am not taking something from them,” he says. “They are giving me a gift by coming to do this for me. We’re sharing something. It’s not me being an outsider, asking them to show emotion. I take photos as we’re talking—about everyday stuff, and over time, we start talking about that day. It’s a shared experience.”

It was obvious to Horin, when he started looking at the photographs, that there was a real connection between Gillespie and his subjects. “He thought about things, like the placement of the hand, the expression, and what this or that person went through. With sports photography, you’re capturing the moment. With this, he’s creating the moment. He’s bringing people into those situations and guiding them. And that’s not easy.”

Since the project’s inception, Gillespie chronicled his progress on Facebook, letting friends and followers see the latest picture, learn about his relationship to the person photographed, read hints previewing his next session, and understand how the project was helping him move through trauma.

“The pictures are really striking,” says Alison Harbaugh, owner of Sugar Farm Productions and previously a Capital Gazette staff photographer. “I like that they are simply lit. I like that he kept every ounce of the character in each face and didn’t mask the reality of where they were in that moment. Each time he would unveil a new portrait or talk about it online, it was as if you’re part of this project. He brings everybody into it and he makes people care by giving them insight into what he’s doing.”

Says Elyzabeth Marcussen, communications specialist at Hospice of the Chesapeake and formerly the Capital Gazette’s community news editor, “Paul is very humble and always a little surprised by the [online and media] attention. He’s not looking for validation. He’s just trying to get through what he’s gotten through. And I think he wants to make sure that the truth is out there. This is his presentation of the truth.”

It takes time to heal from trauma, even longer when it involves losing friends, and not surprisingly, Gillespie still experiences anxiety, depression, and other PTSD symptoms. Being creative can help with the healing process, says Byrd. “When we are in our grooves, as artists, we are in relaxed, meditative states,” she explains. “In that moment, at least, you stop having all those chemicals flood your brain. You’re able to have thoughts and ideas and start establishing your positive neural network. It allows us to start sorting through the information.”

Gillespie acknowledges that his project has helped him with his PTSD. “It’s given me some control back in my life that, over the last year, has been somewhat out of control because of the shooting. It got me doing something creative in my down time. And just the positive reaction has helped me in my healing.” He continues, “This project has been for me, and it’s for the world, to talk about the journalists and what we deal with. But it started off for me.”

Horin sensed a difference in Gillespie, once he dug into the project. He saw how it gave him the diversion that he needed— something to put his energy, heart, and soul into for a while—and how it became something of great importance. He expects his friend to take some of the techniques learned and apply them to his newspaper work as well as other projects. “He’s got to keep growing,” says Horin. “With the show, he’s not only getting the word out about his work, but he’s also getting out the word that journalists matter, and I think that’s a very important topic right now.” █

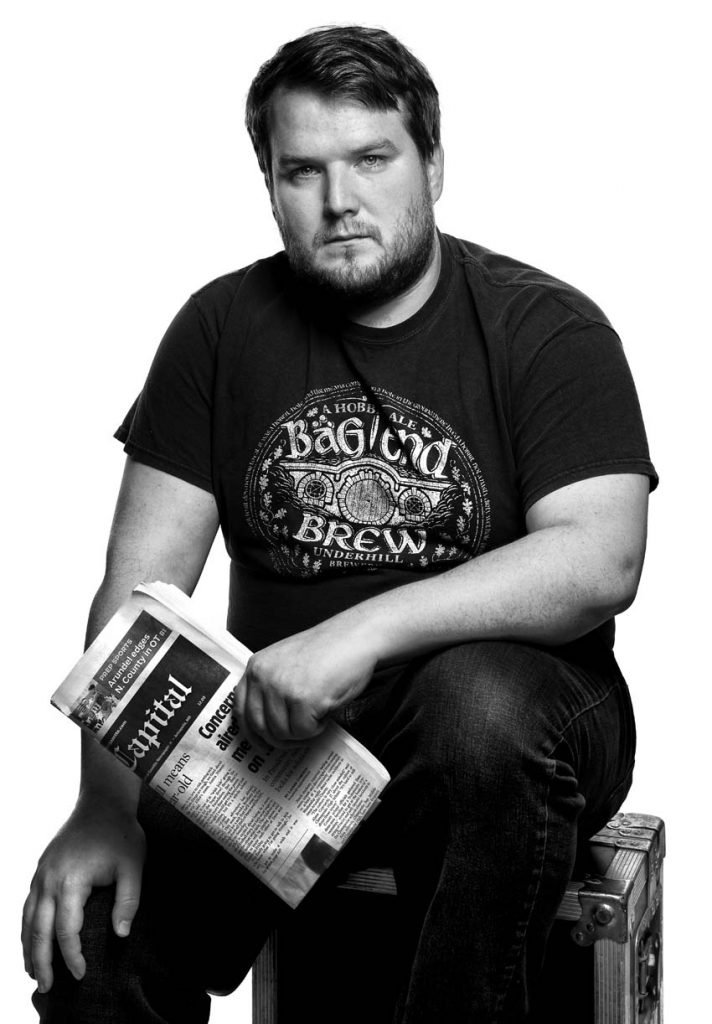

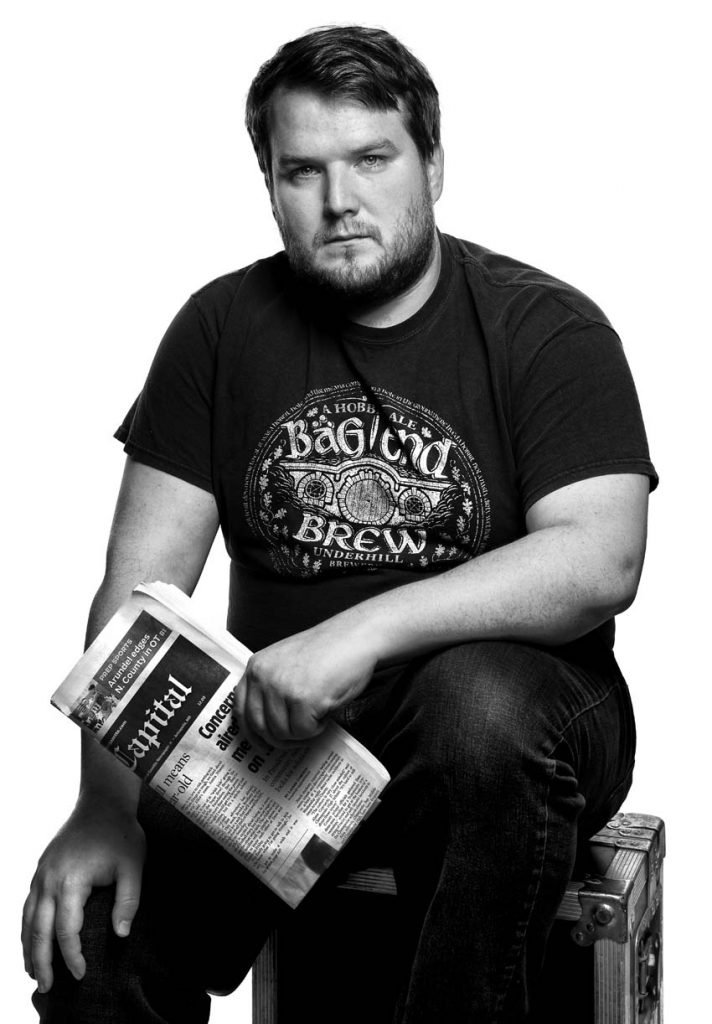

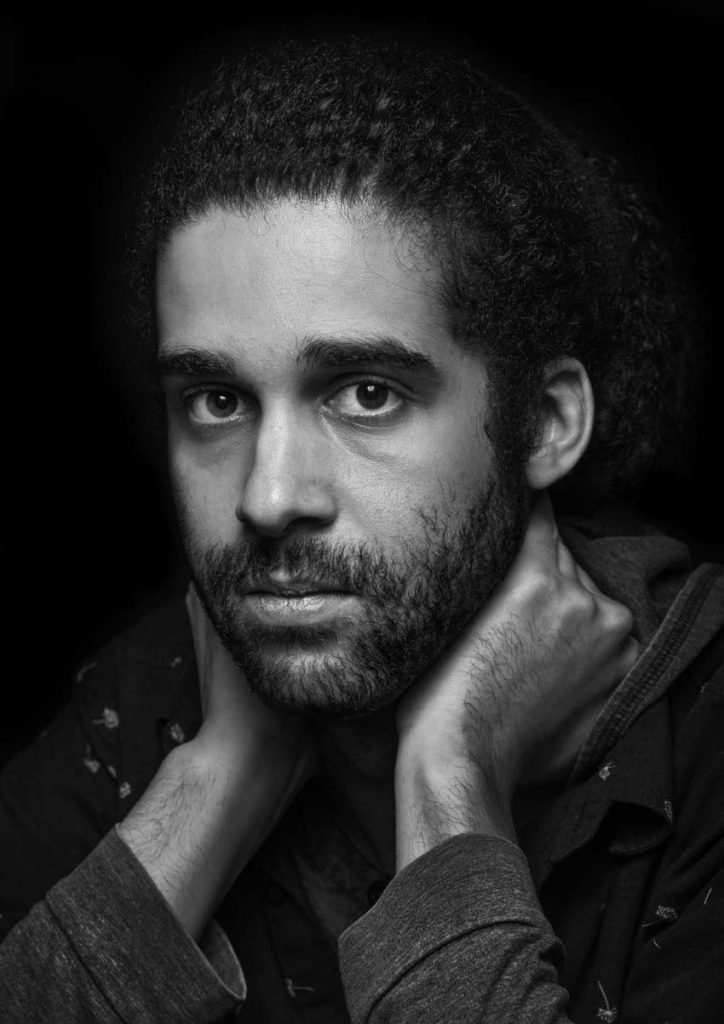

Capital Gazette reporter Chase Cook.

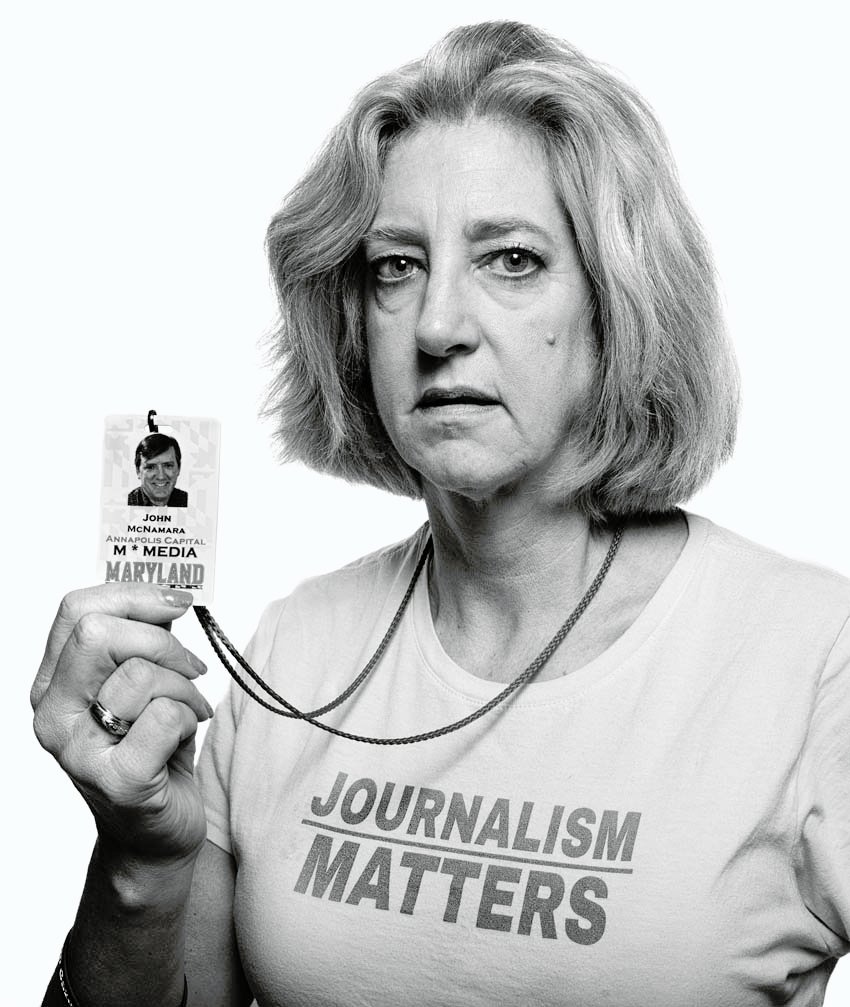

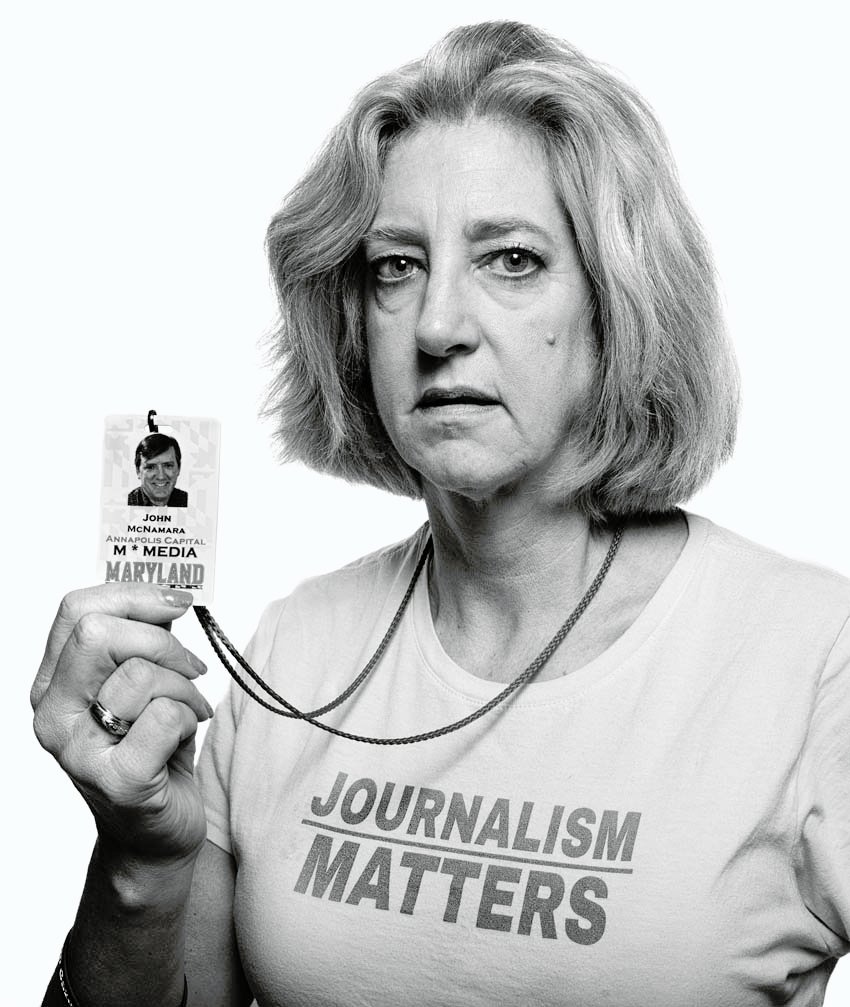

Andrea Chamblee, wife of slain Capital Gazette journalist John McNamara, has shown strength in the months since her husband tragic murder by working to stop gun violence and completing her late husbands book.

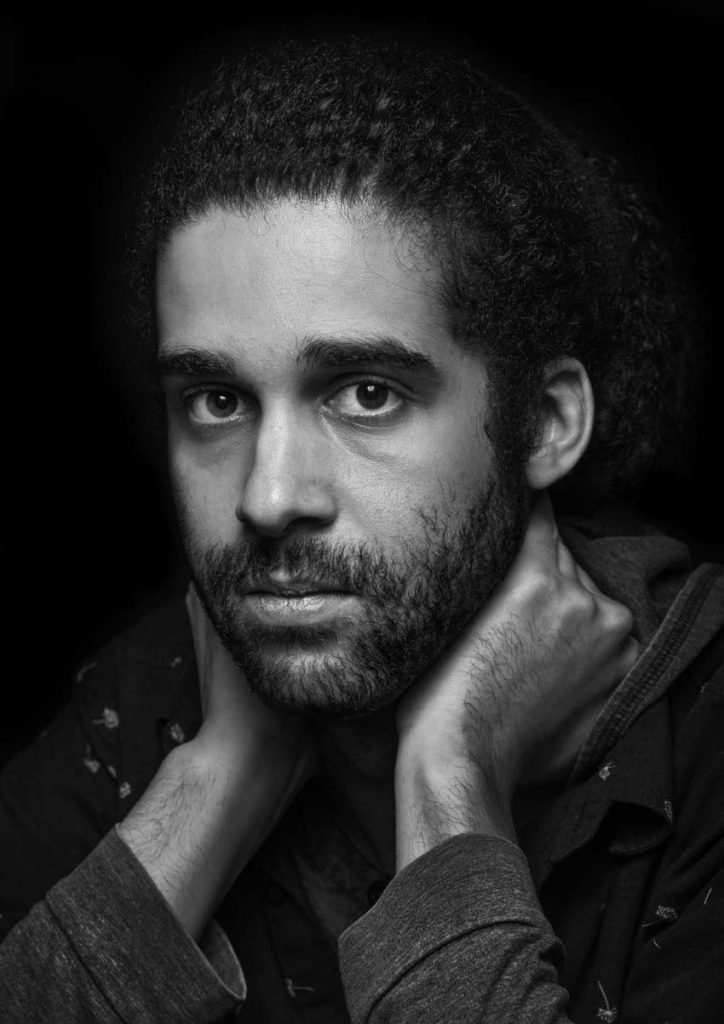

Capital Gazette reporter Phil Davis

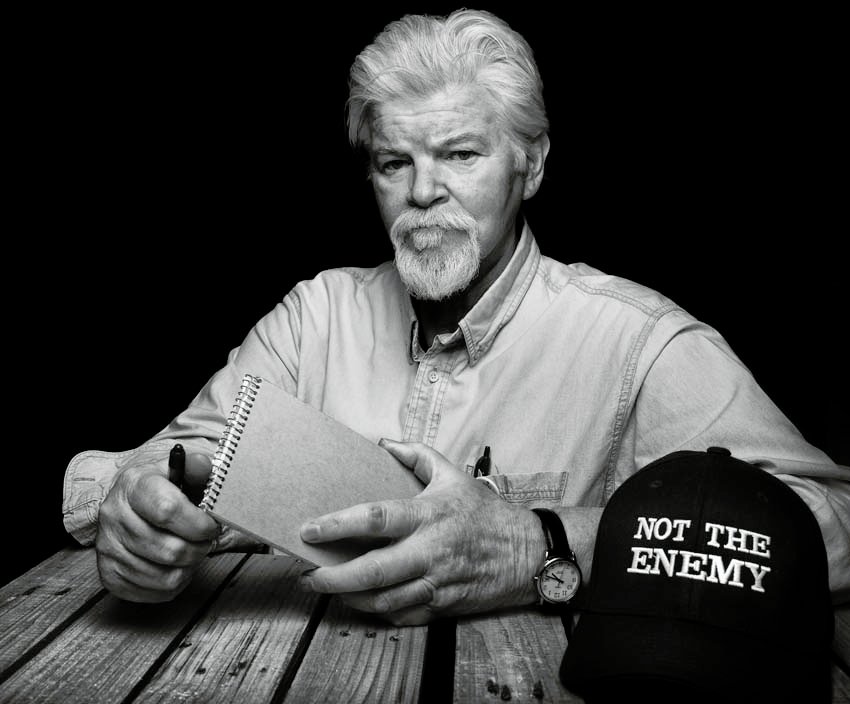

Capital Gazette reporter Pat Furgurson

Paul W Gillespie self portrait in his small studio space. Photo by Paul W. Gillespie. No use without permission.

Capital Gazette Sports Writer Katherine Fominykh

Capital Gazette associate editor Jimmy DeButts