+ By Terese Schlachter + photography & Artwork by Tawny Chatmon

There’s a sobering truth to the fact that gold, in all of its soft, creamy, glinting dreaminess, is, after all, a simple metal. It’s been for so long culturally associated with luxury, importance, and wealth that its reliability, its practical use, is often overlooked. Gold is used to create medical devices, fill teeth, and build space vehicles. It is a supremely efficient conductor. All manner of modern messaging flows through finely strewn and woven glistening gold.

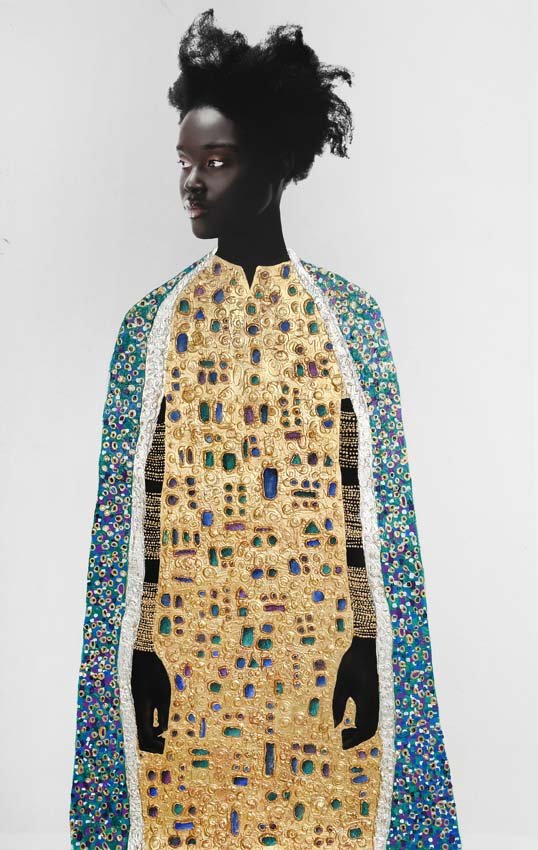

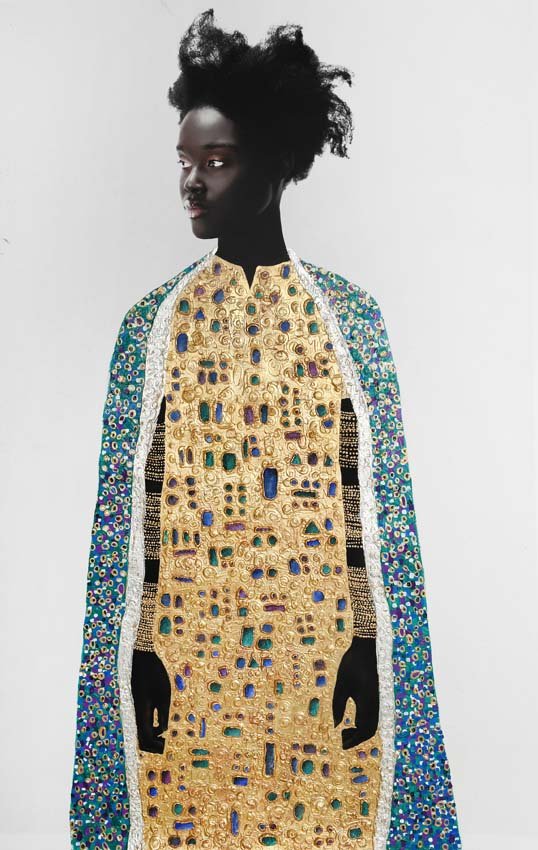

Photography-based artist Tawny Chatmon combines the functional with the aesthetic aspects of the malleable ore. She uses gold as a medium to transmit a visceral message of empowerment by capturing glowing, soulful photographs of her subjects—mostly Black women and girls—using a camera. She then waves her golden wand, elevating them to royalty.

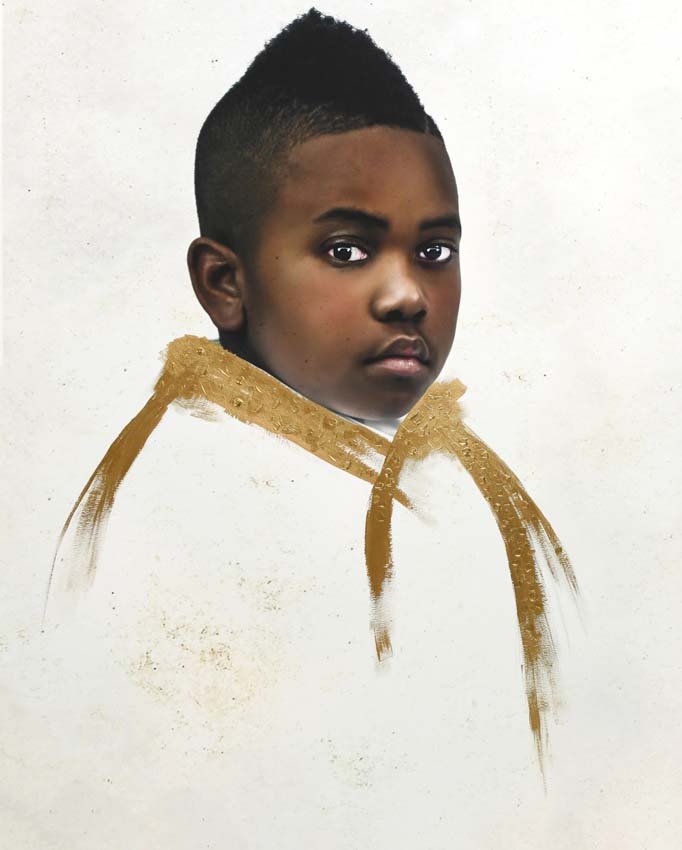

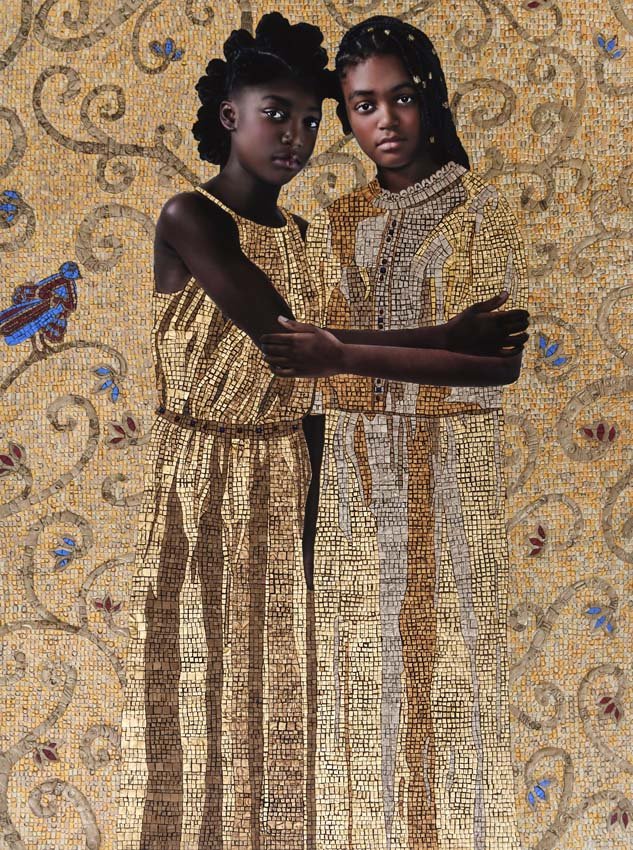

“This is who we are,” says Chatmon, looking around her Annapolis home studio at the large, gilded pieces. Angelic little girls gaze wistfully off the canvas, serious souls exposed. Some have a giggle about their lips. Most are heavily adorned with 24 karat gold leaf and jewel dresses, bracelets, and arm cuffs. They carry the weight of their crowns with graceful ease. “This is how we walk around every day.”

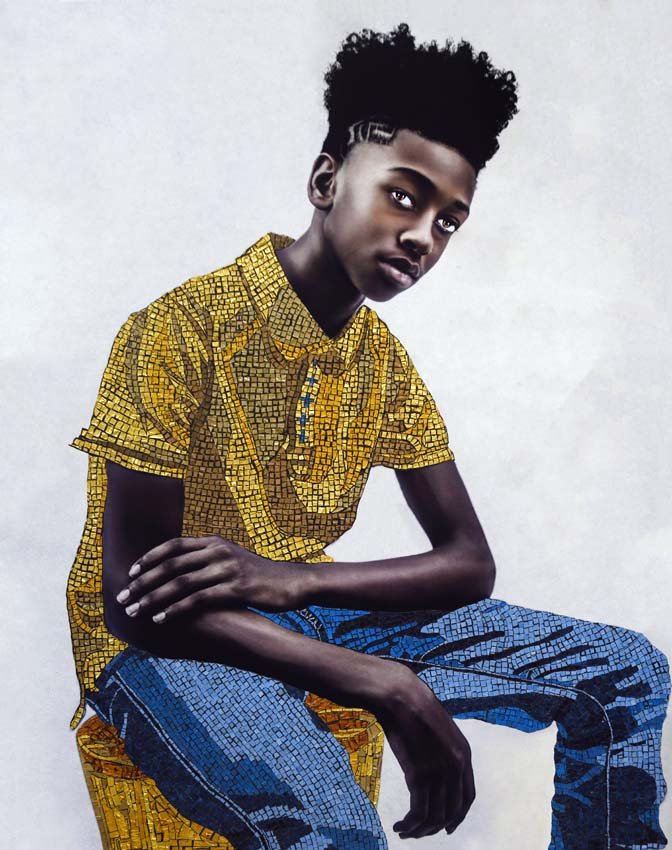

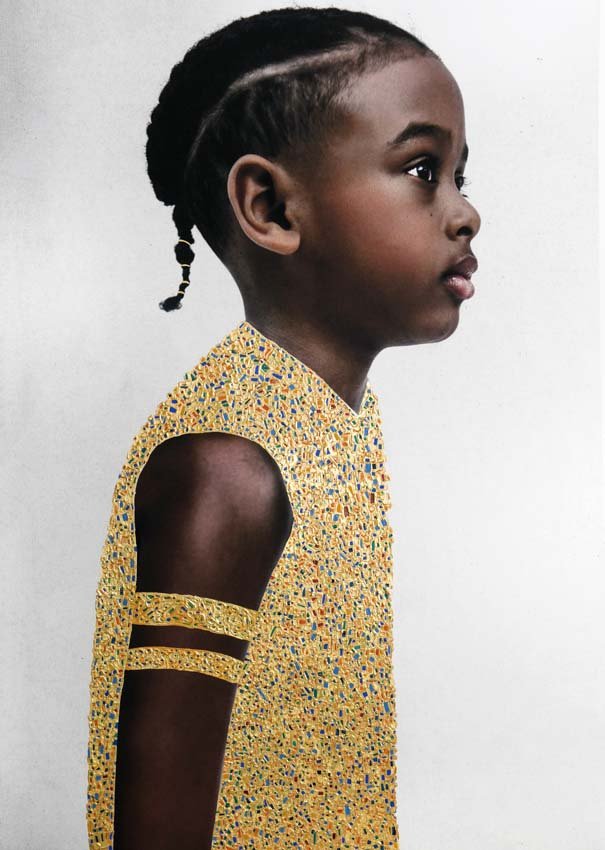

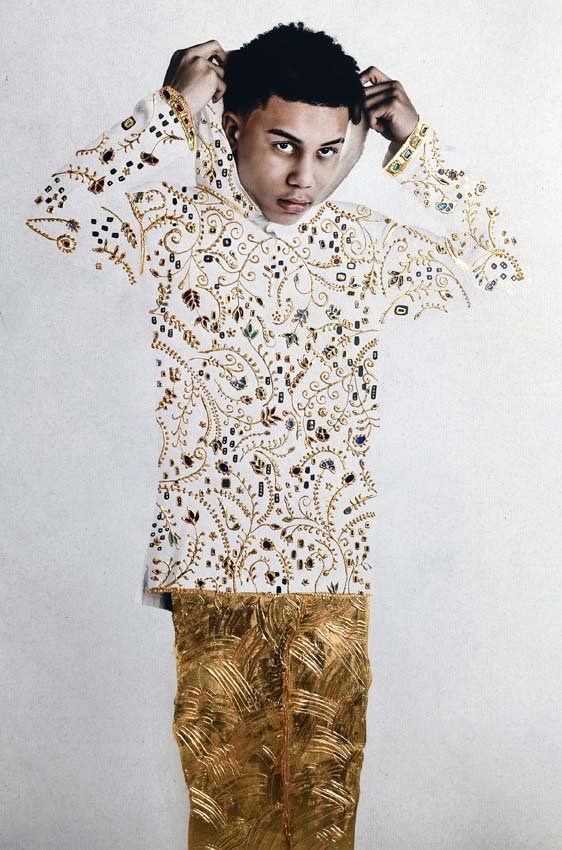

The pieces are meant to laud what some white Americans have seen as unsettling differences, perhaps leading to a false narrative: a little Black girl wearing beaded braids is a burden; a Black boy is a threat. Chatmon’s work, instead, lifts them up. “I think creating works to celebrate us as a whole, especially in a society that has actively sought to elevate features such as white skin, narrow facial features, straight hair (and whiteness overall) while deeming Afro-textured hair, broader features, and darker skin unattractive, helps counteract the negative messages and stereotypes perpetuated by this society,” she says.

Chatmon was an actress in her late teens, became disenchanted, then stepped off the stage to become more of a spectator. Her talent behind the camera earned her commercial photography jobs, but she found herself at arm’s length from her subjects. Her father’s cancer diagnosis drew her into a more intimate form of storytelling.

Over the course of a year, Chatmon documented James “Rudy” Muckelvene’s journey. “I thought I was capturing a story about beating cancer,” she says, her eyes tearing. “I didn’t see the deterioration. In a way, my camera shielded me.” Her father’s death, in December 2010, sent the artist into a months-long fury, destroying old work, painting over tear sheets. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” she says. “I had all these strange feelings.”

In 2012, after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was fatally shot by a neighborhood watch citizen while walking around in a Florida city, Chatmon sunk further into grief. “I was in turmoil,” she says. She devoured every word she could find about that case, turning it over and over in her mind. “My husband told me to get off the internet,” she says. But then, in 2014, 18-year-old Michael Brown was killed by police in Ferguson, Mississippi, and in 2015, Sandra Bland’s controversial death occurred after a white police officer verbally and physically harassed her following a traffic stop in Waller County, Texas. At the same time, the artist began hearing of Black children being sent home from school because of their natural or Black ethnic hairstyles; this happened in Ohio, Oklahoma, Florida, and Louisiana.

Chatmon despaired. Her own children were 10, 7 and 4. “I could scream and yell, or I could create,” she says. She stopped deconstructing her work and began building a different sort of art form—one that initially turns heads, then penetrates the mind.

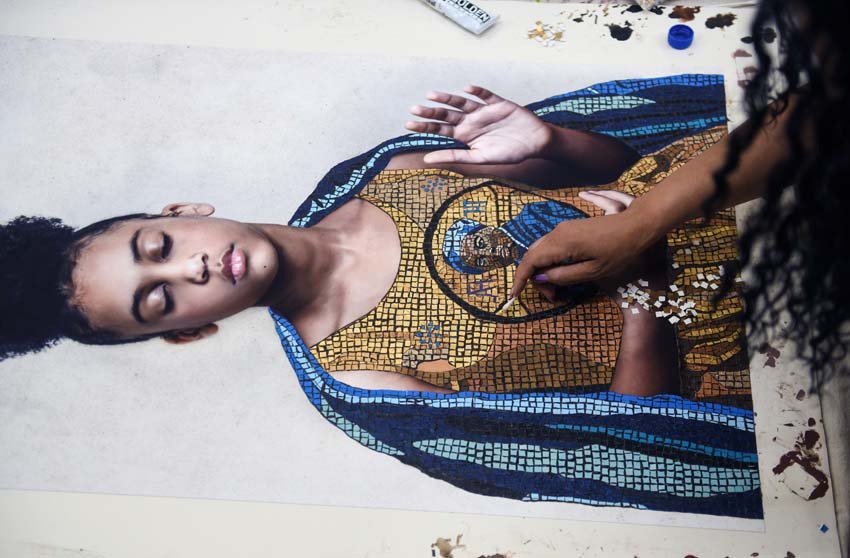

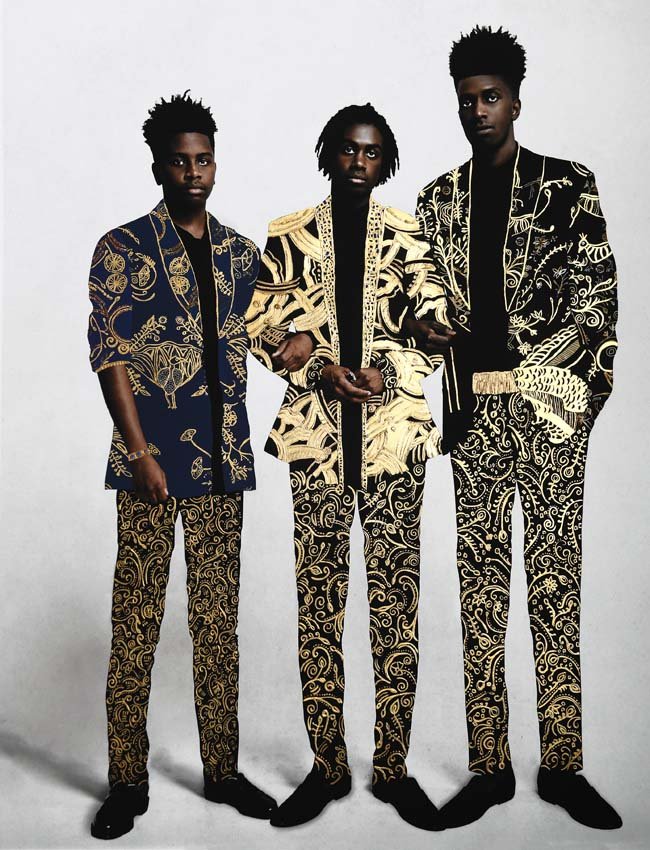

Her work begins with a photo shoot. Sometimes her subjects wear costumes. Often, they wear elaborate hairstyles. Unembellished, the photographs are poignant: two young women stand cheek to cheek; a mother cradles a baby; some look deeply into the lens; others gaze left or right; a few young men appear.

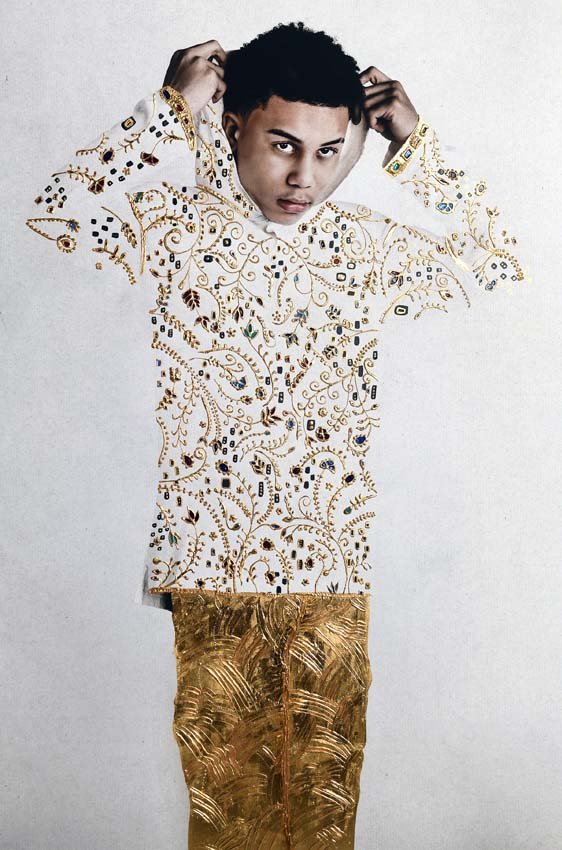

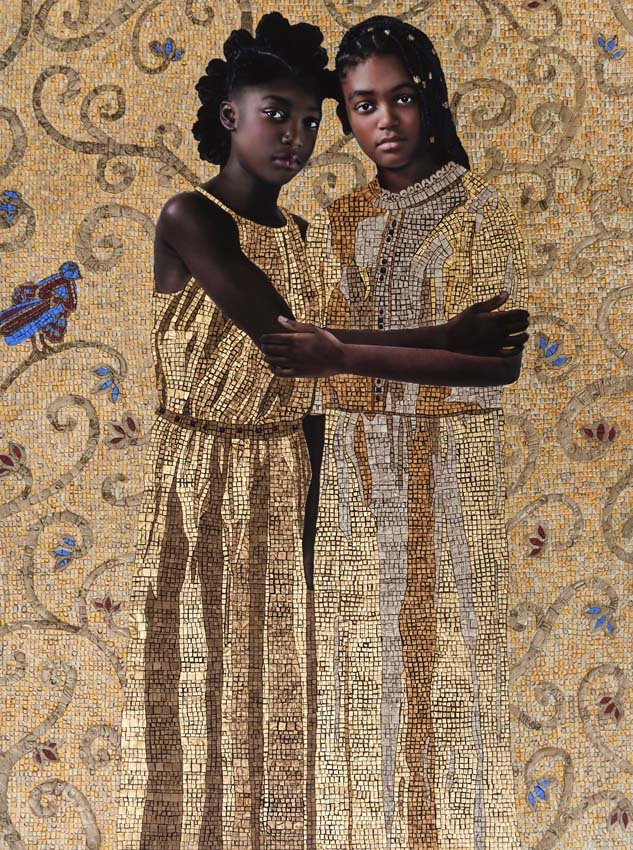

After the shoot, Chatmon selects a print, nearly always makes it larger, and perhaps digitally exaggerates the hairstyle or certain body proportions. Then, she goes to her glitter box—a stack of plain white drawers lining one side of her workspace. She uses gold leaf paint, jewels, and other media to embellish the photos. Blue, red, green, and purple glass pieces form a gold soldered mosaic dress on one girl, a delicate arm cuff on another. One photograph can keep her busy anywhere from four weeks to six months.

Currently, she has seven series online and she’s working on another. In an early collection called “Deeply Embedded,” images of Black women gleaned from the National Archives appear ghostlike in the subjects’ natural hairstyles. Hair plays prominently in Chatmon’s work. It’s adorned, crowned even, with gold flecks, hair bands, and barrettes. In one photograph on her studio wall, a young girl playfully flips her long locks into the air, creating a fan that seems to oscillate. In others, the women wear twists, bunches, and braids—each a work of art—that must have taken hours to create.

Another collection, called “If I’m No Longer Here,” features a Black family bound together beneath a blanket of gold swirls and patterns. One image features a group of teenaged boys. Another shows a young man wearing a white embellished hoodie. Because Trayvon Martin was wearing a hoodie when he was shot. Because young Black men wearing popular fashions are sometimes targets. The model is her son.

Some of her work hangs in Annapolis’ Banneker-Douglass Museum, as part of The Radical Voice of Blackness Speaks of Resistance and Joy exhibit. It is also part of the Galerie Myrtis collection, which focuses on African American artists. Placing the artworks in public spaces is an accomplishment but also part of her overall societal goal. “My kids don’t see themselves in museums,” she says. “Black children need to see art that looks like them.”

The frames come with their own parables. Once, she drove to South Carolina to procure two of the heavy, gold, ornate trimmings. The first she picked up from a man who, upon hearing her intention, told her how happy it made him that the frame, which had once hung in his ancestors’ plantation, would now support work by a Black woman about Black people. Her second purchase had taken her two weeks to negotiate by phone. Once the owner saw her, she refused to sell. When Chatmon finally convinced her to make good on her promise, the owner threatened to make Chatmon stay until the payment cleared. “I wound up paying with cash,” she says. When she gets a frame to repurpose, she often has to remove the artwork that came inside. “Sometimes it’s landscapes. But it’s mostly white people.”

Her style is influenced by Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, whose Golden Phase gained him popularity in the late 1800s through the early 1900s. Klimt often focused on the female form, using gold leaf paint to portray women in what was then considered eroticism. Chatmon has also studied Byzantine artworks, known for the use of gold to depict divinity in religious scenes.

In Chatmon’s work, the combination of the frames, the photography, and the embellishment is visually stunning to the viewer. But that’s not what she’s really looking for. She hopes the work, which she does mostly for exhibitions, winds up in the homes of white as well as Black families. She says she believes her art can play a small part in shaping and shifting the views of those who witness it.

“I want the viewer of my art to not be able to walk past—to be overwhelmed with what the work is saying,” she says. “I want them to wonder, to look beyond the beauty of the work, and understand the message. And I don’t want them to forget what they saw.” █

For more information, visit tawnychatmon.com.