+ By Mary Ann Treger

At first glance, Annapolis might appear to be an ultra-casual town focused on sailing and historic buildings—a place where streets are lined with wandering tourists mixed with Naval Academy midshipmen and t-shirt clad boaters sip a brew while savoring a crab cake. That image may be warranted given its proximity to the Chesapeake Bay, but this “sailing capital of the world,” as it is known to some, has a more sophisticated side when it comes to classical and contemporary music.

This small capital city with its modest population of fewer than 50,000 attracts famous performing artists, and it’s not unreasonable to wonder why. The city’s venues are hardly posh. As charming as it is, Maryland Hall is an old, converted high school with a simple 750-seat auditorium—no elaborate lobby, no Veuve Clicquot at intermission, no fancy crystal chandeliers. There is no comparison with the sophisticated concert halls a short drive away. The elegant Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall in Baltimore and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, both designed by world-famous architects, have seating capacities of close to 2,500 and offer a posh environment worthy of highly celebrated artists.

On the contemporary side, Rams Head On Stage seats 320 people in a cozy room—different than the 3,000-seat theater at the MGM National Harbor in DC. Could the Annapolis allure be venues without attitude—egalitarian and unstuffy?

For some performers, the small size of Rams Head On Stage is a big plus. “Not one seat in the room is further than 48 feet from the stage. Intimacy is one of the reasons performing artists love coming here,” says Kris Stevens, vice president of programming. Over the years, the venue has welcomed dozens of famous celebs, including Kevin Bacon, Greg Allman, Kevin Costner, Kris Kristofferson, Billy Idol, Wynonna, and Judy Collins.

On the classical side, José-Luis Novo, artistic director and conductor of the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra, says that attracting world-class talent is the result of working with soloists and artists management companies over many years to develop relationships. Novo’s résumé is a big part of the appeal. The Fulbright scholar has master’s degrees in music and musical arts from Yale University. Entering his twentieth season with the Annapolis Symphony at the time of this writing, he is the longest-serving music director in its history. Before coming to Annapolis, Novo conducted orchestras from Palm Beach, Florida, to Thailand.

“When world-class artists come to play with us, we work very hard to offer them a memorable experience,” he says. “Our orchestra is very receptive. When we put this kind of talent in front of them, they give 300 percent, and I think everyone notices. Once you develop a good reputation, it becomes less difficult to lure other guest artists.”

The symphony is also flexible with scheduling. “We make it difficult for them to resist,” says Novo. He often allows artists to choose the repertoire they would like to play and offers date flexibility. “We give them the star treatment they deserve.”

His approach must be working. Over the years, opera’s acclaimed mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves and world-famous violinist Midori have appeared on the Maryland Hall stage. Graves’ career includes performing at the Metropolitan Opera, and she is best known for singing the title role in Georges Bizet’s Carmen and Camille Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. Since debuting with the New York Philharmonic at age 11, Midori has performed alongside the late famed conductor Leonard Bernstein and cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

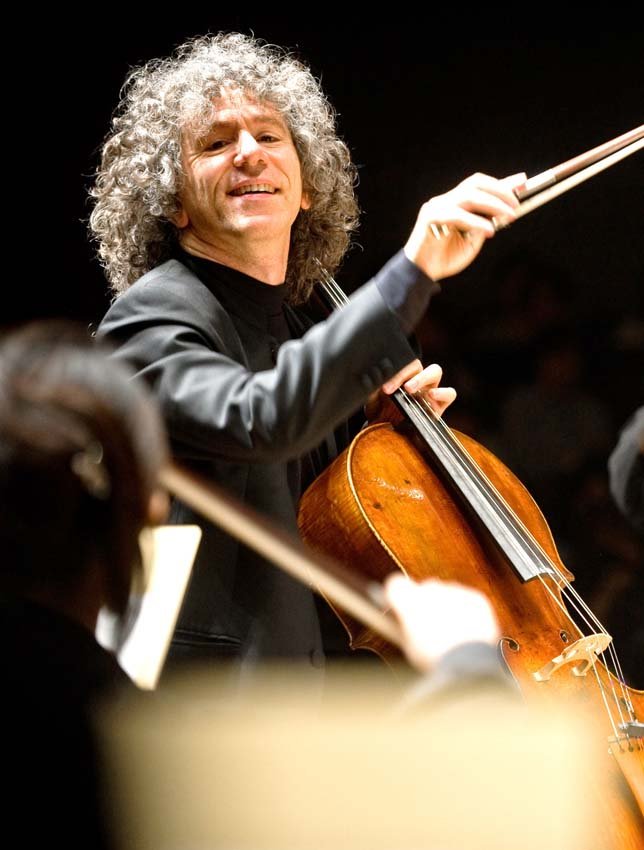

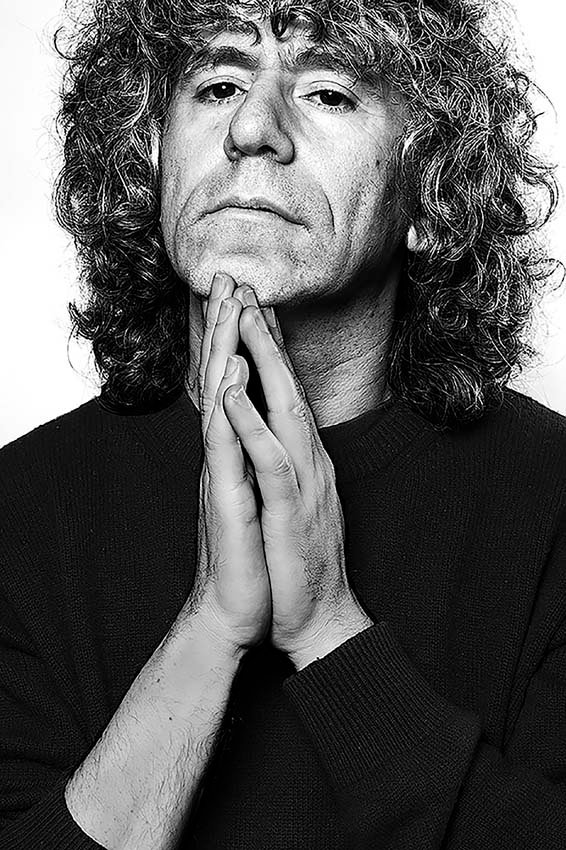

Steven Isserlis, an acclaimed British cellist, educator, and author, performed last year with the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra. He has performed with such prestigious orchestras as the Berlin Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, and New York Philharmonic. Even his cello has star quality, as he plays on the “Marquis de Corberon” Stradivarius of 1726, on loan from the Royal Academy of Music.

Isserlis played Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 at Maryland Hall. He says he doesn’t like to play exclusively for big-city audiences. “Audiences in smaller towns like Annapolis are more supportive and more grateful that you’ve come there; they are more engaged.”

Isserlis said that he first visited Annapolis after graduating from Oberlin College & Conservatory. “I met this lovely old man who lived there and invited us to visit,” he says. “He told us [that] in the eighteenth century, Annapolis had four opera houses.”

Indeed, according to Mary-Angela Hardwick, vice president of education and interpretation at Historic Annapolis, the city’s passion for the performing arts dates back centuries. “In 1771, a theater opened on West Street with great public enthusiasm, and in 1873, an opera house opened in the Masons’ building on Maryland Avenue featuring theatrical productions and vaudeville shows,” she says. “In the early 1900s, the Old Fourth Ward was home to an impressive music scene. Its nickname was Annapolis Harlem. Small venues on Calvert, Washington, and Clay Streets featured performances by rising stars, including Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey.”

“A thriving arts community has always been in this city’s genes,” says Andy Noel, an Annapolis Opera board member and a cultural historian. “In 1752, the location that is now the Truist Bank Building on the corner of West Street and Church Circle was the home of the first West Street theater. The Hallam Theater, built in 1769, was likely where Rams Head [On Stage] is now on West Street. The Masonic Opera House, built in 1872 at 44 Maryland Avenue and Prince George Street, is now an office building. There were even more venues that have either been torn down or there is no record of where they were built.”

Folk singer Judy Collins is also well known for her work as a political activist, filmmaker, record label head, musical mentor to young singers, and speaker for mental health advocacy and suicide prevention. With 36 studio albums, 9 live albums, 24 compilation albums, and 21 singles in her repertoire, she made time in 2024 to return to Annapolis for two sold-out performances.

“It is always a privilege to be at Rams Head,” says Collins. “The size of the room or location doesn’t matter. What matters is that you are in a room with an audience that loves you, and this audience at Rams Head has always been on my side. It is very exciting to be here.”

At 85, this Grammy Award-winning artist still has the magic touch. Collins ended both shows with Stephen Sondheim’s “Send in the Clowns.” The cliché “you could hear a pin drop” was an appropriate reflection of the audience’s response and affection.

Prominent musicians enjoy performing in Annapolis for many reasons. Maybe they are seduced by the simplicity of this picture-perfect town or its intimate performance spaces. Or perhaps they enjoy inspiring young artists. Denyce Graves ended a performance several years ago with a popular 1930s song. “Don’t blame me for falling in love with you . . .” she sang, and the audience fell in love with her. Graves’ advice to young artists is “Follow your passions, even if they seem unconventional or risky. Doing what you love will bring you fulfillment and joy.”

One of the great things about Annapolis is the endless stream of music waiting to be heard.