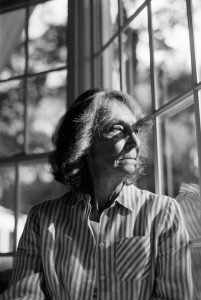

+ By Leigh Glenn + Photos by Caitlyn Mae

Hannah Ives is a reluctant sleuth who lives on Prince George Street in Annapolis and solves mysteries wherever life leads her. In Daughter of Ashes, by Annapolis-based mystery writer Marcia Talley, Ives and husband, Paul, refurbish a cottage on the Eastern Shore, only to discover a mummified toddler in the chimney. That incident—coupled with a murder and near-murder—and Ives’ fortuitous work as a researcher of old, moldy, local land records, makes the mystery a page-turner, taking readers on a journey through Chesapeake Country, MD, with Big Chicken, the 1950s color line, and various cover-ups.

Talley has led Hannah Ives fans through 16 adventures, and counting. Her foray into mystery writing was a “shameless Nancy Drew/Hardy Boys rip-off” in eighth grade. Despite her English teacher’s admonition to “write what you know,” she didn’t let that stop her. She dove into Alfred Hitchcock films and kept writing crime fiction until full-time work and motherhood meant shelving the stories. Then a breast cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment alerted her to things she needed to finish, including mysteries to be written.

An Oberlin College alumna, Talley majored in education. At the time, women were encouraged to have something to fall back on. She taught elementary and middle school until her first pregnancy; women had to stop teaching when the baby bump became apparent, and the tent dresses worked only for so long. Talley had to go on maternity leave three months before labor. During that time, she typed catalog cards for the Bryn Mawr School library in Baltimore, the same work she’d done in college to help pay tuition. That launched her into a career as the cataloger at St. John’s College after her husband, Barry, accepted a teaching job at the US Naval Academy and the family moved to the Annapolis area in 1971. More education—a master of library science at the University of Maryland—and a knack for programming led to work integrating computer systems for the US government.

Stints at Sewanee Writers’ Conference and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference helped Talley develop her chops in storytelling—mysteries in particular. She entered her first work, Sing It to Her Bones, in an annual conference contest and was surprised when she won. Agents phoned, unsolicited, to represent her, and she got a three-book deal with Bantam Dell publishing.

Readers of mysteries enjoy the goosebumps, the waves of hope elicited by the protagonists, the hair-raising climaxes, and the releases that follow. But for mystery writers, the motivations may be different.

Says Talley, “I don’t have to tell you that the real world is a messy, violent, frequently unjust place. Mysteries can be a respite. In my fictional world, I call the shots. Justice is served and the villain suitably punished. I love the puzzle aspect of the mystery, planting clues and dropping red herrings. As for me, personally, there have been a lot of people in my life who needed to die. In a mystery, I can bump them off with a stroke of my pen, and it’s cheaper than a therapist. I find many literary ‘book club’ novels deeply depressing, and as for romance, well, I’ve met a lot of people I’ve wanted to kill, but very few that I’d want to sleep with.”

Protagonist Ives, whom Talley describes as “a bit like a superannuated Nancy Drew,” has some things in common with her creator. She, too, is a breast-cancer survivor who loves to sail and is married to a professor at the Naval Academy. “She’s funnier than I am, though,” says Talley, “and braver. Younger and prettier, too, although just as curious and fiercely independent.”

Talley writes first drafts in long hand, during which Ives offers wry comments on what’s going on around her. She edits her first drafts while typing them into the computer, then prints out the novel triple spaced and goes somewhere quiet for more editing, eventually sharing her revisions with her writing groups. The process takes about a year. She’s been with an Annapolis mystery critique group since 1996, which first met at “the late, much lamented Mystery Tales Bookshop in West Annapolis” and now at Barnes & Noble, and also belongs to one in Hope Town, Bahamas, where she and her husband sail during the winter.

In the wake of her novels, Talley has left a trail of bodies, in Eastport and Ginger Cove, on the stage at Mahan Hall, on the DC Metro, one floating face down in the South River, and elsewhere. She aims for accuracy: “If someone tosses a bloody knife into a dumpster behind McGarvey’s Saloon, there’ll be a dumpster there.” One fan wrote to Talley that she took a tour of Annapolis, visiting all the local sites that Ives did. “Maybe I should produce an annotated tourist map?” she muses.

If only there were time. Once Talley finishes a book, she looks to TV and newspapers for potential future story hooks. Finding one, she asks, “How can I get Hannah believably involved in this?” Then she dives into research. For recently submitted work, she gets back suggested changes from editors, then copyeditors take a crack, followed by her own set of proofs. After publication, Talley supports the work with readings. She pays little attention to debates about formats—print or electronic. What’s most important is fair compensation and that people want to read what she writes. “We write the best novel we can, deliver it to our publishers, sit back, and go with the flow.” █