+ By Terese Schlachter + Photos by Josh McKerrow

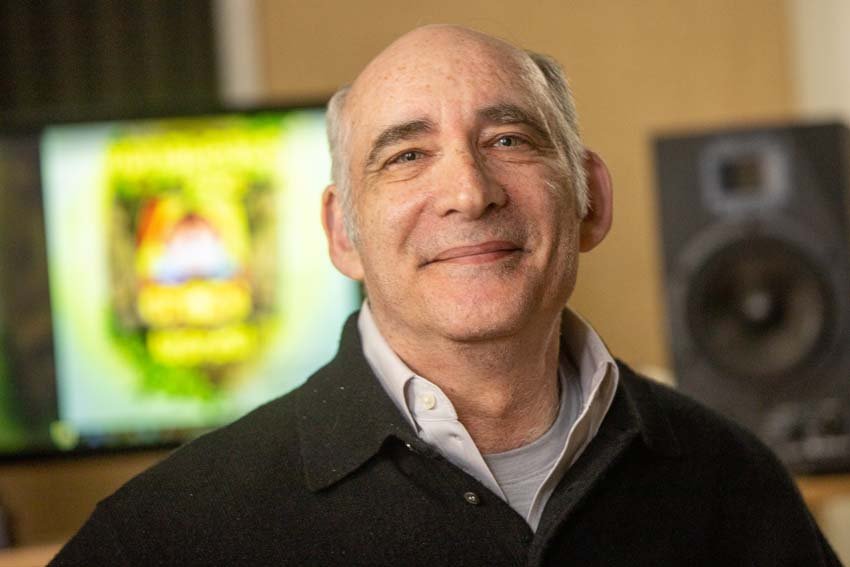

Howard Siskind is an accountant. He manages neat rows of numbers, aligning sums and balancing totals. He is exact, calculated, if you’ll pardon the pun. The work is finite, tangible, algorithmic.

Imagine, then, what happens when things, people, and words in Howard’s world don’t add up. Actually, words spoken by people. Or a person—the person being his wife. “She’s always done it. I found it charming,” Siskind says of the “crazy words” his then-girlfriend, Karen, would utter. “She would say ‘escalvator’ to mean escalator, mixing in the word ‘elevator.’” A meal at a Mexican restaurant might be “Aunt Chiladas.” They were living in “And Arundel County.”

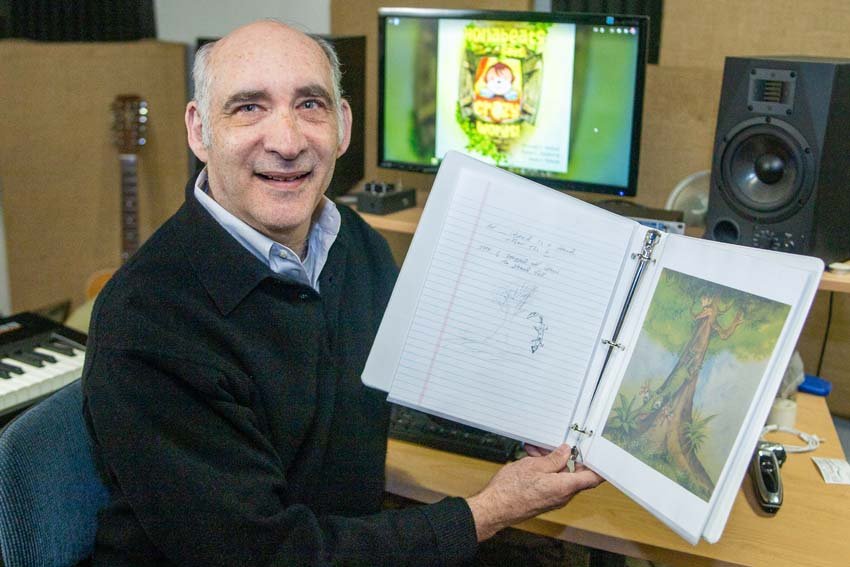

Howard started writing the words down, and the pages lived in a drawer for years. Karen and Howard married and had a daughter, Sarah, who liked quick-tongued “izards” and the color “ellow.” Eventually, the rhythmic nature of Howard’s mind began aligning the crazy words into short poems and then into a children’s storybook. Honabeats Says: Crazy Words is a rhyming puzzle of sorts, accompanied by whimsical drawings in rich, dusty, museum-like hues. Honabeats is the story’s protagonist. The name itself is a crazy word that was coined by Sarah. The actual definition was never revealed by the accidental young wordsmith, so a Honabeat became a monkey-like creature who hides amid the “izards” and “ellow” bananas.

The authors see the book as a learning tool for children who may struggle with spelling or pronunciation. “It gives me joy,” says Karen, reflecting that her sometimes inverted vocabulary provides enlightenment to the younger set. Sarah, who is now in college, says she’s very proud of her father’s work on the book. She is also a writer, so her author credit is particularly meaningful. “I think it’s really neat to have my childhood words turned into a book and to see my parents’ and my name on the title of a children’s book,” says Sarah. “I know he’s been thinking and writing all of this down for a long time.”

The compact, 35-page story is also available internationally, as it’s found a place at the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. “That’s my ‘just can’t believe it—wait, what, huh, pinch me I’m dreaming’ surreal moment,” gushes Siskind about the book’s inclusion in one of the oldest and most well-known libraries in Europe.

Growing up in Annapolis, Howard took piano lessons when he was 6 years old, but by the time he was 12, his tastes were running more toward rock music and the electric guitar. At age 15, he and his junior high and synagogue buddies were blowing out neighborhood basements to the sounds of Black Sabbath and Grand Funk Railroad, ringing the ears of parents who insisted everyone be at their home dinner tables by 6 p.m. They named their band Stillwaters and played gigs—mostly dances at the old Annapolis YMCA building on Hilltop Lane, which is now occupied by the Salvation Army. “I remember they would use a projector to throw psychedelic images on the wall behind us,” says Howard.

After Howard met Karen, he was inspired to write the song “When I Saw Her” while sitting on her parents’ porch in Ocean City. In 1996, Howard played the guitar and Karen sang at their wedding. Some music that Howard composed as a teen, called “I’m Flying High,” matured into a nostalgic tune about parasailing with Sarah. Now, at age 65, with his daughter in college and retirement on the horizon, he’s not letting go of his guitar or his pen. He plays music and composes every Thursday evening in his friend Todd Kreuzburg’s studio, turning out songs that he releases through the online distributor CD Baby. The musical compositions often mirror the process of the print product, the framework built upon a dreamy story line. The artwork for the singles are drawn from Howard’s sketches, as are the illustrations in Honabeats.

Howard says that his lyrical writing is not very different from his accounting work. The numbers have beats and patterns, similar to a poem. And he says that there is a visual element to both. “You need to use summaries, tables, charts, and graphs to show people a visual story of what’s going on,” he says. “This is no different than the poems in Honabeats or the stories in my songs. I try to create a vision within all my writings.”

No doubt the Hona-beat will go on, in story and song. █