+ By Dylan Roche + Photos by Gregg Patrick Boersma

While some contemporary artists may be trying to outdo one another, pushing the boundaries of Expressionism or Cubism or some other kind of -ism, others such as Rick Casali are preserving the tradition of portraying the human face and form in a way that artists have been striving to do for millennia.

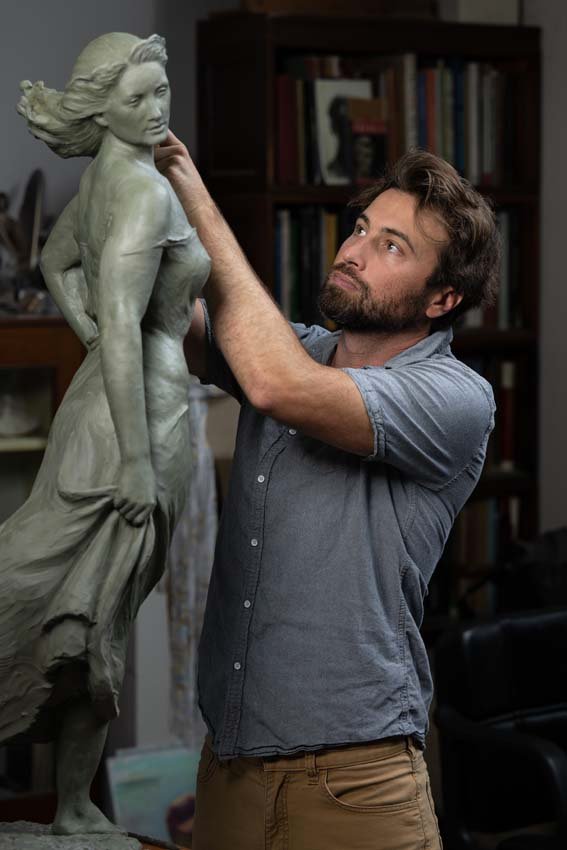

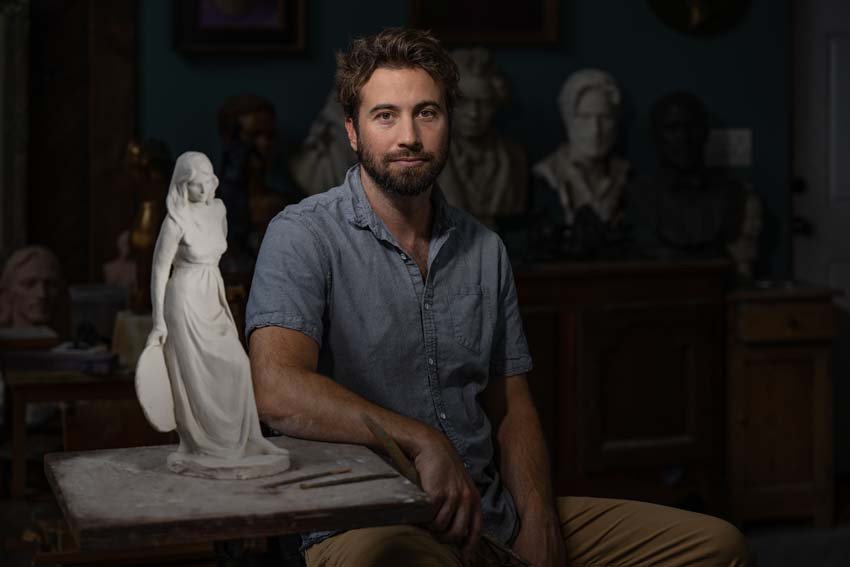

From his Galesville studio, the professional sculptor and portrait artist painstakingly captures the humanity of his subjects—not just the way they look, but who they are—doing what Casali recalls one of his mentors once describing as capturing their spirit and having the patience and drive to chase it out of them.

One of Casali’s mentors is esteemed Annapolitan painter Cedric Egeli, who started training the then-teenaged Casali. “He said, ‘You have a feel for people. You have a love for people. You’re interested in people. That’s what being a portrait artist is about,’” recalls Casali. Before he began studying under Egeli, Casali showed promise. Having taken up drawing as a child, he met his first mentor at age 14, when he started taking classes with John Ebersberger at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts. There, he learned to draw the human figure and eventually study the craft of working in color with full oil painting. But his studies as an artist took an unconventional path as he got older, and he found that his original plan for a four-year degree from art school wasn’t for him.

“Unfortunately, most art schools don’t teach this anymore,” says Casali, referring to his portraiture and sculpture. “Because of postmodernism theory and all this, all the traditional artists were kind of pushed out, back in the ’60s. My mentors were like, ‘You can go to college, but I don’t think it’s going to be any better than when I was there in the ’70s,’ but I still had to go see for myself.”

After a year and a half at Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, he found that his mentors were right. They were not teaching what he wanted to learn, in fact, they were discouraging it. He left college and instead studied directly under Egeli and his wife, Joanette. Their tutelage wasn’t a formal program, but he was able to live in the loft above their art studio on their farm, paint alongside them, and receive their critiques and input on his work every day. “[Egeli] would equate getting better to making more money,” Casali explains. “He’d say, ‘If you can understand what I’m trying to teach you about how the skull is put together and about the action of the body, instead of getting $5,000 for your payment, you’ll get $50,000.’ He was trying to put a fire under me.”

Once Casali’s work started to sell, he realized that art was his professional calling. The change to full-time artist was at first intimidating because he was accustomed to working in restaurants and earning a regular paycheck. However, the calling was strong. At age 23, he began teaching at Maryland Hall, which allowed him to build a reputation for himself while also selling his work in galleries and taking on portrait commissions.

He started sculpting in addition to painting about eight years ago, finding it to be a nice balance. “I think painting keeps you fresh and fluid, and then sculpture makes you think about form and keeps you honest about the proportions of a person,” he says. Neither medium is without its challenges. Casali points out that sculptors don’t have to worry about color the way painters do—using layers of color to create the illusion of three dimensions even though they’re only working with two. Moreover, a painter only has to worry about seeing someone from a single vantage point, instead of considering what that person looks like from all sides. “When I’m with a bunch of painters, I feel like a sculptor; when I’m with a whole bunch of sculptors, I feel like a painter,” he says. “When I’m doing one, I kind of miss the other.”

As with his paintings, which start out as a sketch, Casali’s sculptures all begin with a smaller prototype that he creates out of clay. He then builds the larger version. When he’s working with terracotta, he has to keep the clay wet to prevent it from cracking, wrapping it with plastic if he needs to continue working on it later. More often, he works with Plasticine™, an oil-based clay that doesn’t dry out.

Sometimes a solid clay sculpture can weigh up to 100 pounds, as is the case with a sculpture of a woman that he recently created on commission. “A smarter artist would have used foam to fill the center and keep it lightweight,” he jokes. Once the clay form is complete, it is then captured in a rubber mold. The mold is used to create a wax version, which he touches up with fine details before covering it in a liquid ceramic, called slurry, to create a ceramic shell. The ceramic is then sent to one of several foundries he works with to make the finished bronze sculpture.

While some sculptors revel in being hands-on in pouring their own bronze, Casali prefers to outsource this step so he can focus on doing the part he loves most. “I don’t have that urge,” he says. “I can appreciate the craft of it. Probably because I was trained as a painter. I wasn’t trained in the welding and all the nitty-gritty. I’d rather focus on the design.”

Whether he’s sculpting or painting, Casali acknowledges that he’s part of a long-standing tradition. There’s a timelessness, he says, to these realistic depictions of people, one that lets people living in modernity see themselves in faces from antiquity. “Why can we look at a Greek sculpture and have a connection to it, even though it’s 3,000 years old?” he asks. “Or a painting that was done 500 years ago?” It’s one of the reasons he’s so passionate about sharing his knowledge with others, particularly when he knows that art schools aren’t prioritizing traditional art techniques. “If you don’t teach young people about this, then it’s going to be lost in the next generation, and they’ll have to start over, like cavemen trying to figure it out,” he says.

Although he has led classes in the past at Maryland Hall, Anne Arundel Community College, and St. John’s College, as well as other places across the country, he now teaches primarily out of his studio. The rise of video conferencing in recent years has let him reach a wider breadth of students from all over the world, even as far as Europe and Asia. His online presence has also gained him a following of global art connoisseurs who have bought his work.

No matter how great his reach becomes, he never loses sight of the excitement of a sale. “It’s always a thrill when someone buys your artwork,” he says. “You think, ‘Someone saw the value in what I did.’” Those sales also remind him that he’s making a living doing what he loves. “Very few people get to do this professionally,” he says. “I think if I abandoned it, I would be a fool, because it’s a blessing to be able to do it.” █