+ By Zoë Nardo + Photos by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio is an avowed packrat who, over the years, has developed an award-winning method to her madness.

Her basement barely has enough room for all of her stockpiled stuff. There are silver process black-and-white photographs from her days as a photographic lab technician and photographer, toys from her childhood, desiccated bouquets, old books, tools, scraps of wood and lace, and containers of every shape and size. Overhanging light fixtures reveal workbenches and tables with works in progress, glass-fronted boxes, costume jewelry, wooden wheels and gears, and old encyclopedias. Neatly labeled drawers contain dried insect corpses, pins, cancelled stamps, miniature animal figures, and a plethora of other things. This space, her “little supermarket of found objects,” as she calls it, has been part of her work area for some 12 years.

Petruncio’s other studio is on the main floor of the Arnold home she shares with her husband, Emil, and their two large dogs, Dylan and Coco. There, the bulk of her work takes place, nowadays. It’s a cozy place where her iconic box assemblages take shape.

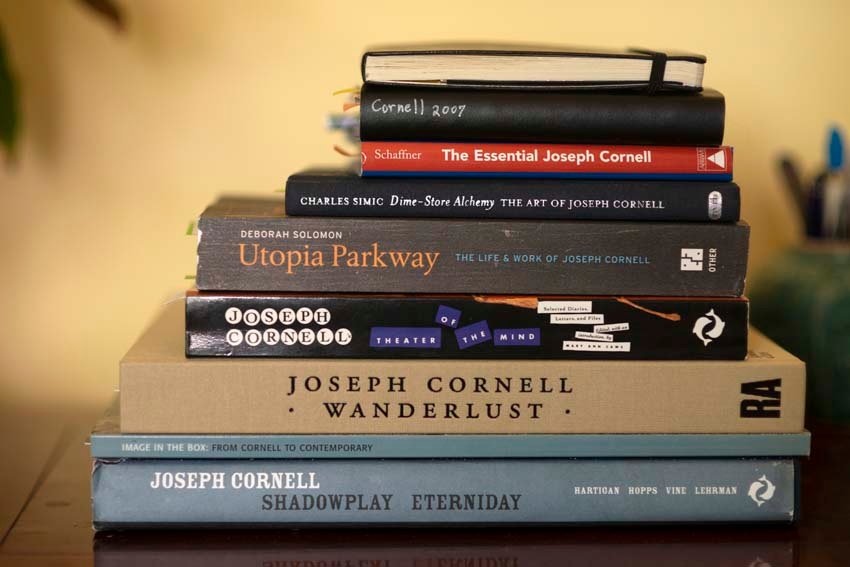

The art of assemblage, or found object, dates back to Pablo Picasso’s Still Chair with Caning (1912) but made headlines in 1917, when the Society of Independent Artists accepted Marcel DuChamp’s submission of a urinal called Fountain. Nearly 60 years after that influential event, Petruncio came across an article in Time magazine showcasing the work of Joseph Cornell, a self-taught surrealist and master of assemblage. He became well known for creating small shadow boxes, “memory boxes,” that invited onlookers to explore his wondrous imagination. “I was immediately hooked,” says Petruncio, recalling Cornell’s three-dimensional collages containing photographs, eggs, shells, fabric, and other mementos combined together in poetic juxtaposition. One of his most highly regarded pieces, L’Egypte De Mlle Cleo De Merode, was featured, revealing an apothecary filled with glass bottles containing all sorts of found objects, from snippets of text on paper to beads and marbles. Petruncio reread the article several times and immediately set out to emulate the feeling she got while being immersed in that magical creation. She collected old vitamin bottles, and bits and pieces of things to place inside them. The collection expanded, marking the beginning of her journey as a found object (objet trouvé in French) assemblage artist.

She began her studies at the University of New Mexico, pursuing a bachelor’s degree in fine art. As a granddaughter and daughter of artists, she felt it her goal to carry on the family tradition. While her studio art curriculum touched only briefly on found art, the idea that the discarded can have a new life through artistic expression wasn’t a hard concept for Petruncio to grasp. Photography became her main emphasis, and she was drawn to abandoned buildings, rocks, graveyards and the stark landscapes of the Southwestern desert.

Petruncio dropped out of college with only two semesters left. After working in the photography world for a few years, she decided to see what the military had to offer and enlisted in the US Air Force. Her love of photography stuck with her through her time there, and she eventually returned to school and earned her degree.

Over the next 30 years, as she crossed state lines and bodies of water, her collection of castoffs continued growing, but with little assembling. After graduating, she obtained a commission in the US Air Force and was assigned to Naval Air Station Keflavik, Iceland. There, she met Emil Petruncio, who was a stationed oceanographer for the US Navy. They eventually settled in the Annapolis area, where for nine years she cared for her ailing mother.

Two months after her mother’s passing, in January 2007, the Smithsonian Museum of American Art presented Joseph Cornell: Navigating the Imagination, a retrospective exhibit. With great excitement, Petruncio packed a notebook and headed into Washington, DC, to take in the show. She spent hours roaming through the cases and stands, and got goose bumps after seeing the Cleo De Merode apothecary box in real life and knowing she had come full circle. “[The exhibit] happened at a perfect time for me,” she said. “My time was my own. I was completely free to concentrate on this experience.”

Petruncio tries to evoke an imagined narrative of the objects chosen for a piece while also creating a sense of mystery that the viewer may interpret in countless ways. Her goal is to create small worlds that tell a story, but the process of developing the narrative is never the same. “I often tell people my process is like making sausage,” she says. “It’s not something you’d want to see.” Sometimes she will find a scrap of painted wood or some paper packing material and be inspired to use it as a starting point. Other times, she will pick up an object that someone has discarded and immediately know that it has a story to tell but will let it sit for months or years, allowing the story to germinate and grow.

She works on several different pieces at a time to allow paint to dry and glue to set. If one piece isn’t coming together, she’ll move on to another. The waiting game with each piece reminds her of her days in the darkroom. “My favorite part . . . was seeing that image come up in the developer like magic,” she says. “So now, I’m layering acrylic mediums, paint, and materials on, and then I’ll leave it alone overnight. I can’t wait to get up in the morning and see what happened. I just love it.”

A few of her favorite pieces were years in the making. Her tribute to Van Gogh, Vincent’s Muse,was started in 2007 but laid aside for a year before being completed. It features a deliberately chipped miniature pitcher—a nod to one of his self-descriptors—a knothole with an iridescent glow within, representing his penetrating eyes, and the feel of the Dutch interiors often seen in classic Dutch paintings. Aegis, named after the shields used by mythical characters Zeus and Athena, was once a vine-covered crab basket lid found in the schoolyard behind her house. It stayed in her basement for over two years until she formed it into what she says is the epitome of found art—incorporating natural and man-made elements to indicate a natural shield, leaving in place some of the vines and adding a paper wasp nest. The piece has been exhibited so many times that she’s often had to replace the wasp nest. Petruncio invites viewers to touch and interact with her works. She’ll secure ribbons to the front and wooden wheels to the sides, inviting a tug or a push. She hopes generations young and old will fall in love with the genre, just as she did.

Petruncio has managed to turn her fascination with the discarded and unwanted into more than she ever dreamed. Within her first year as an artist, she became a member of the Maryland Federation of Art (MFA), and a piece of hers was accepted into the first juried show she entered. She has since been accepted into exhibits at the Mitchell Gallery at St John’s College and regional and national juried shows. She has participated in group shows with other artists and has been invited to show work at the Maryland House of Delegates offices, The Galleries at Quiet Waters Park, and more. She has won five honorable mentions and three juror’s choice awards for her pieces in MFA exhibitions.

While most of her works are shadow boxes, she is currently challenging herself to create larger pieces on flat surfaces such as canvas and wood panels. She is looking forward to a solo show at the New Deal Café in Greenbelt in August 2020. █

To learn more about Angela Petruncio’s work, visit

www.angelapetruncio.com.

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, works out of her home studio in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio’s piece inspired by fellow found object artist Joseph Cornell, “And A Little Child Shall Lead Them (Homage to Joseph Cornell)” Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio’s piece inspired by Vinvent van Gogh “Vincent’s Muse” Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio’s piece “Bishop’s Obsession” Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio’s piece “The Inner Workings of the Universe” Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio’s piece “Play Thing” Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio’s piece inspired by her relationship with her father, “Daddy’s Little Girl,” Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of pieces by found-object artist Angela Petruncio Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of pieces by found-object artist Angela Petruncio Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

“Aegis,” by found-object artist Angela Petruncio, hangs on her wall at her home in Arnold, MD Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

“Aegis,” by found-object artist Angela Petruncio, hangs on her wall at her home in Arnold, MD Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

“Women’s Work,” by Angela Petruncio hangs on her wall at her home in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of found objects and future pieces of art in the home of artist Angela Petruncio. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, holds a photograph of herself as a photography student at the University of New Mexico. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio, found-object artist, holds a photograph of herself as a photography student at the University of New Mexico. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of found objects collected over the years in the home studio of Angela Petruncio, in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of found objects collected over the years in the home studio of Angela Petruncio, in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of found objects collected over the years in the home studio of Angela Petruncio, in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of found objects collected over the years in the home studio of Angela Petruncio, in Arnold, MD. Photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of Joseph Cornell books and personal notes that have served as inspiration for fellow found-object artist, Angela Petruncio sit on her table at her home in Arnold, MD photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of Joseph Cornell books and personal notes that have served as inspiration for fellow found-object artist, Angela Petruncio sit on her table at her home in Arnold, MD photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

A collection of Joseph Cornell books and personal notes that have served as inspiration for fellow found-object artist, Angela Petruncio sit on her table at her home in Arnold, MD photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio flips through a book of Joseph Cornell’s work, a fellow found-object artist, who has served as an inspiration for her own work at her home in Arnold, MD. photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid

Angela Petruncio flips through a book of Joseph Cornell’s work, a fellow found-object artist, who has served as an inspiration for her own work at her home in Arnold, MD. photo by Kaitlyn McQuaid