+ By MacDuff Perkins + Photos by Kaitlyn McQuaid

When life gives you scraps, make a quilt.

-unknown

Cynthia Keller moves like a whirling dervish around her dining room table, where her extensive quilt collection is heaped in colorful piles of organized chaos. Keller has been collecting and making quilts for decades, and the assemblage offers insight into the storied trajectory of American craftwork. Some of the blankets are antiques, faded with frayed edges and flattened by time, while others are new, vibrant, and downy, with a modern eclecticism. All are clearly beloved.

“This block is from the 1930s,” she says, pulling out an unfinished square of elaborate patchwork waiting to be incorporated into a larger project. With skilled fingers she traces stitches invisible to the untrained eye. “These were all done by hand, and hardly anyone does that anymore.”

Quilting, from the Latin culcita, meaning “stuffed sack,” can be dated back more than 5,000 years. It was a way to use spare cloth and create functional artwork that could provide warmth as a bedcover or greater insulation as wall art. In America, quilts were popular during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; their elaborate patterns and stitching displayed the artistic prowess of their makers. Initially considered a leisure activity for the wealthy, quilting’s place in society changed during the Industrial Revolution, when textile fabrics became commercially available.

It also became a popular pastime for women who gathered to work either independently or on one quilt. Quilting bees, as they are now known, allowed women to be in each other’s company to craft, pray, and commune. One of the oldest existing Australian quilts was made by a group of 30 female convicts in 1841 as they were transported by ship from Woolwich, England, to Hobart, Australia.

Quilting bees today have many elements of early Americana while also being very different. “Quilters want to be around people who want to be crafting,” says Jane Mullinix, copresident of the Annapolis Quilt Guild. “We meet up at each other’s homes, so food is always involved. We drink a lot of wine.”

Mullinix is a hand quilter—she sews the layers of fabric together by hand with a needle and thread, not a machine. “There aren’t too many of us,” she says. The craft takes patience and skill. She learned how to sew as a teenager, when she wanted clothing that she couldn’t afford to buy in stores. “I made everything, from bathing suits to prom dresses,” she says. She fell into quilting when a friend went away to college and Mullinix made the covering for her friend’s dormitory bed. She’s been a Guild member since the early 1980s.

Today, the Guild makes quilts for different recipients. “The Lighthouse Shelter has been one of our partners for years,” says Mullinix. “We provide the quilts for their beds, and when the people leave, they can take their quilt with them.” The Guild also donates mastectomy pillows, scarves, baby hats, receiving blankets, and mittens for patients at Luminis Health in Annapolis. Patients who receive infusions or chemotherapy treatments can receive a Guild quilt to keep them warm during their treatments.

“The charm of a quilt is that there will never be any two alike,” says Keller, who has been an active member of the Annapolis quilting scene for the past 40 years. Her fingers flutter as she talks about fabric arts. “My quilts tell stories of all the places I’ve been and the people that I’ve known.” Butterflies, birds, flowers, and feathers pepper her fabric patterns, with bright pinks, oranges, and turquoises showcasing her many personal transformations over the years.

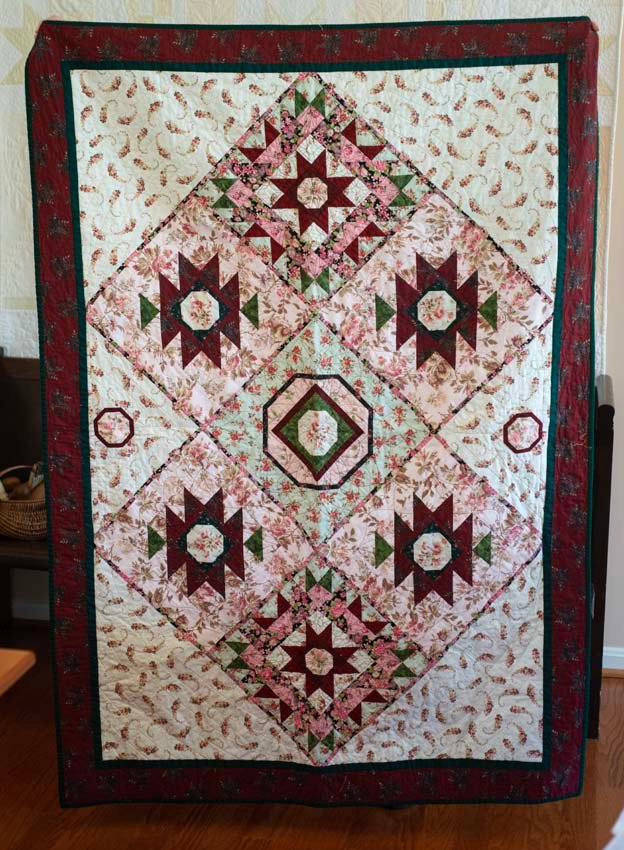

Quilts come in different styles. Sometimes made of one solid piece of cloth, sometimes made of patchwork squares, traditional quilts place blocks on a grid in a pattern and typically have repeating colors and patterns, often with motifs having Biblical references such as the Cross and Crown, God’s Eye, and Jacob’s Ladder. Modern quilts generally lack grids and symmetry and instead have patterns that play with negative space and minimalist designs. Crazy quilts go a step further, using fabric to create pieces of art with no repeating or geometric patterns.

Fabrics can be chosen randomly or have a much greater significance. “Sometimes when we’re making a memorial quilt, the fabric will be from the deceased,” says Keller. Shirts and jackets will be transformed into comforting pieces of art, often with a pocket square or button for personality. “People like them because they’ll still smell like the person.”

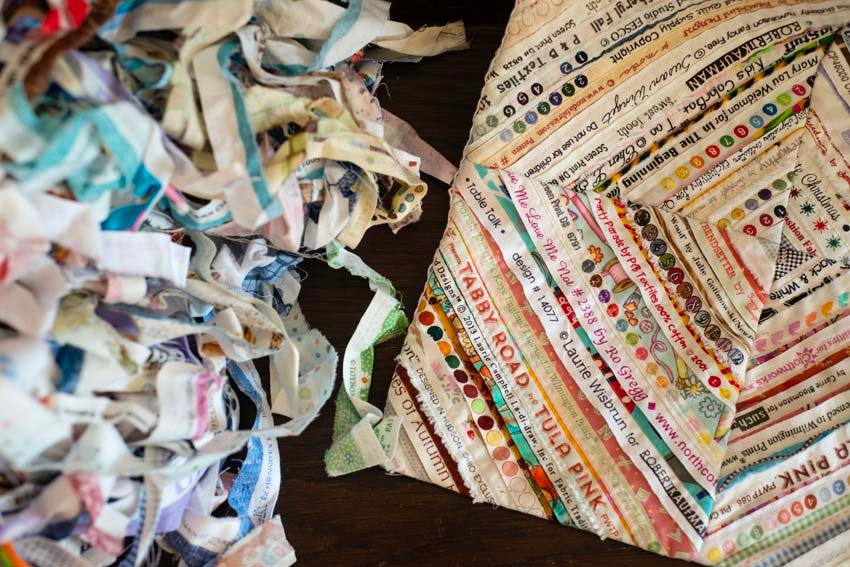

While some may view quilting as a primitive craft, there are artistic intricacies spanning several mediums, and it’s possible to have a number of artisans involved in the creation of one bedcover. There is design and fabric selection. Sometimes the squares are orphan blocks; other times the same fabric trails across sections. A theme may tie blocks together or each may be unique, such as a collection of various stars (e.g., the Sawtooth, the Ohio, or the Hunter) spanning across the blanket, sewn by different artists.

After the top face of the quilt is finished, thick batting is sandwiched between the quilt top and a backing piece of fabric. Elaborate stitching is then traced over the top and often the back of the quilt. “If you’re old-school, you hand-sew or tie your layers together,” says Keller. “There are many longarm quilters who will finish your quilt top with beautiful stitching.” She showcases the minuscule stitches that run across the back of her quilt to create a floral pattern. Longarm quilting machines are becoming a more popular way to bind layers. They take significantly less time to create the patterns, and the stitches are more uniform and tighter. “When it’s time for the actual quilting, it’s best that I send my quilts off to a longarm quilter,” says Keller. “This process makes an average quilt look mighty fine.”

Keller works with the Guild as well as with Sew Time Ministry and Project Linus to donate quilts to families in need. “Each one is a piece of art, and sometimes it’s hard to let them go,” she says. “Knowing they’re going to someone who really needs it is comforting.” Sew Time Ministry is affiliated with the Catholic Church and donates quilts, baby clothing, mittens, and more. Project Linus provides handmade blankets to children under age 18. In spring 2023, Project Linus worked to raise funds and donate blankets to Haitian weather event survivors who are still displaced and needing essential housewares. No quilting experience is necessary to become involved with either organization or the Annapolis Quilt Guild.

“This is my Gypsy Quilt,” says Keller, turning a bohemian pattern over to display the name patch—providing her and the quilt’s names—with her handwriting. She runs a finger over the hardly visible stitches. “I made this quilt at a time in my life when I was finding my freedom and my independence. Quilting brings me a great deal of happiness, and I put that into this quilt.” Keller’s Gypsy Quilt is folded lovingly and placed on top of the pile. Her personal arcana is stitched into its blocks like the words on the pages of a book, then filed in a library that goes back generations. █