+ By Leigh Glenn + Photography By Alison Harbaugh

In the mid-1960s, filmmaker Mark Hildebrand’s family moved to Annapolis’ Wild Rose Shores neighborhood, across from then-Londontowne, which fed his imagination. He grew up in music—first piano, then trumpet, from elementary school through college. But after three years of music education at the University of Maryland, he switched to business but never finished.

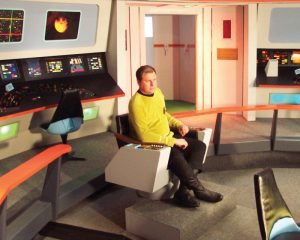

After waiting tables and tending bar, he went into automobile and then health insurance. That led to his running a trade association benefits program and enabled him to buy a house. The work failed to nourish his creative energy, so he turned to community theatre, and then film with Starship Farragut, a group of DC–area Star Trek fans, and later served as a film festival screener.

In 2009, Hildebrand launched the nonprofit Make Your Mark Media to support his films. Today, he works parttime for the City of Annapolis television station, City TV, which includes filming city council meetings and preparing for a film about the legacy of Queen Anne. He is best known for Anthem: The Story Behind the Star-Spangled Banner, which has been viewed by millions of people on Maryland Public Television, PBS, and now Amazon Prime, and Brookeville: Capital for a Day. Here, he shares how that work came to be.

In 2009, Hildebrand launched the nonprofit Make Your Mark Media to support his films. Today, he works parttime for the City of Annapolis television station, City TV, which includes filming city council meetings and preparing for a film about the legacy of Queen Anne. He is best known for Anthem: The Story Behind the Star-Spangled Banner, which has been viewed by millions of people on Maryland Public Television, PBS, and now Amazon Prime, and Brookeville: Capital for a Day. Here, he shares how that work came to be.

Up.St.ART Annapolis: Tell us about where you grew up and your earliest influences.

Mark Hildebrand: Wild Rose Shores is on a peninsula, so no through traffic, a paradise for a kid. Luckily, there were a dozen or so kids within a few years on either side of me, and we had the run of the neighborhood, jumping into the creek and the South River. What we did usually involved the water—fishing, crabbing. We’d play army and “stranded on a desert island,” football, softball, tag, and flashlight tag after dark. A lot of fantasy play—Dungeons & Dragons. The idea of sitting around and creating a world, describing things to people, putting yourself in a different frame of mind—that appealed to me. In school, Alice Harper was the band teacher at Annapolis Junior High, seventh to ninth grade. She taught us integrity, poise, and helped develop some amazing musicians.

UA: It’s obvious from your films that you have an abiding interest in history.

MH: In the 1970s, I was helping my mom at an outdoor event at Londontowne [today’s Historic London Town and Gardens]. We both dressed in early American outfits. While there, a reenactment group was shorthanded. I asked if I could help, and they had me carry the cartridge to the front of the cannon. I got heavily involved in reenacting during the bicentennial, including the Battle of Yorktown. I always found history I couldn’t relate to incredibly boring. But with early American history, I could close my eyes. I could understand how Alexander Hamilton felt as he charged the redoubt at Yorktown.

UA: What drew you into filmmaking?

MH: Filmmaking didn’t come until a little more than 10 years ago. I sold my house right before the housing bubble burst, in 2004, and paid off all the debt I’d been carrying. I had a little money set aside and I was turning 40. I said, “This is going to be the decade when I’m going to be creative and I’m going to be artistic.” I got much more involved at Colonial Players and Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre. I’ve been a Star Trek fan my whole life and heard about Starship Farragut. I got to play their Klingon and then wrote, directed, and edited an episode where the captain meets George Washington, whom I also portrayed. Later, after screening hundreds of films for the Utopia Film Festival in Greenbelt, all the fear began to disappear for me. I could make something as good as that. Why not?

MH: Filmmaking didn’t come until a little more than 10 years ago. I sold my house right before the housing bubble burst, in 2004, and paid off all the debt I’d been carrying. I had a little money set aside and I was turning 40. I said, “This is going to be the decade when I’m going to be creative and I’m going to be artistic.” I got much more involved at Colonial Players and Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre. I’ve been a Star Trek fan my whole life and heard about Starship Farragut. I got to play their Klingon and then wrote, directed, and edited an episode where the captain meets George Washington, whom I also portrayed. Later, after screening hundreds of films for the Utopia Film Festival in Greenbelt, all the fear began to disappear for me. I could make something as good as that. Why not?

UA: What was the genesis for Anthem?

MH: I asked myself, “Why don’t I follow my brother and sister in-law [David and Ginger, who specialize in colonial music] and listen to a couple of their lectures and put together a companion DVD for their music CDs?” It was 2010. There was a lot of buzz around the 200th anniversary of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Why not tell the story of where the melody came from? The more I learned, the more I thought, “This is a stand-alone film.”

UA: And Brookeville?

MH: Brookeville happened because of Anthem. The town of Brookeville, Maryland, had gotten a grant to make a documentary: “Would you make it for us?” But a major challenge was taking their idea of what they wanted and turning it into something that would tell a story—not a travelogue, but the story of [President James] Madison’s three nights on the run from the British.

UA: The figure of Francis Scott Key, like others in the Mid-Atlantic and the South, has drawn greater attention lately as more people see past inequities through the lens of the present.

MH: Several years ago, a lead pastor at a megachurch in California made a patriotic YouTube video, with music from the movie Patton, about Key, telling a story about how, during colonial days, Key rescued 100 prisoners on a boat in Baltimore. He massacred the facts. But look at the video comments: one person noted that the incident with Key happened in 1814. A comment to that was, “Why do you hate freedom?” That’s the debate we’re faced with today—misinformation, instantaneous assumptions, and judgments without caring about the facts. I have no problem with monuments being taken down that were erected in the Jim Crow era with the intention of keeping African Americans in their place. The Key monument was erected at the time to honor a man for writing that anthem. He had slaves. He has a complicated history like Thomas Jefferson has a complicated history. When it comes to film, if you can watch something and say, “I want to know more about this person, I want to find out more about what was going on at that particular time,” that’s great. That’s what Star Trek did for me—educated me on a bunch of issues. You walk away with a moral lesson you didn’t know you got, and what better medium than film to deliver that? █