+ By Leigh Glenn + Photos by Alison Harbaugh

At 18, Towson native Lee Bonner was on his third visit to Leeds Music Corp. in New York City, where he and his bandmates—the Lafayettes—had brought another set of 78 rpm demo discs. In a large room, an old fellow took the discs into a phone-booth-sized glass enclosure to listen. Just as before, the man shook his head from left to right—the first demo was a no-go. But then his head shook up and down—yes to the second song, “Nobody But You,” cowritten by Bonner and Frank Bonnarigo, the band’s singer. Leeds agreed to publish the song and secure a contract with Jubilee Records.

For musician and filmmaker Bonner, now 74, that moment was one of many that dollied about his creative life. “I can’t tell you how exciting it was, watching that old guy shaking his head,” Bonner recalls today.

In fourth grade, Bonner learned to play trumpet and read music and joined the school band. As a teen, he received a guitar one Christmas and took lessons at Fred Walker’s on Howard Street in Baltimore, getting there by streetcar and bus. A friend later asked him to join his band, but the band’s guitar player was better than Bonner, so Bonner switched to bass. The Lafayettes, named after the street in Baltimore, played soul music and R & B at school dances, teen centers, Catholic Youth Organization events, the Alcazar and Dixie ballrooms, and fraternity parties.

When the band members heard that Leeds Music’s Tommy Chianti would be at the Battle of the Bands on the local Buddy Deane Show, they decided to play original songs, even though it meant they were unlikely to win. Bonner, the main songwriter, said the band thought it more important to get a song published. They came in third, and Chianti invited them to bring their songs to New York for vetting.

At the time “Nobody But You” garnered approval, one of Bonner’s girlfriend’s relatives worked for RCA Victor’s songwriter-producer duo Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, who had recorded Elvis Presley, Sam Cooke, and Della Reese. He took the demo to the duo’s secretary. About a week later, Bonner and friend Phil Huth were heading for Smetana’s Delicatessen when Bonner’s mother called him back to the house to answer a phone call from New York. It was Peretti, wanting to record “Nobody But You.” “Phil and I were so excited, we went down to the basement and wrote a song,” Bonner says. That song, “Life’s Too Short,” became the flip side and the hit.

“Nobody But You” was reportedly a song that The Beatles enjoyed playing before they became famous, Bonner says, but “Life’s Too Short” boosted his band’s demand locally as well as at venues such as Yale University. The Lafayettes never spoke of their brush with renown, but its potential crossed Bonner’s mind. “It was a little scary—‘If we have a huge hit, they’re going to run our lives and we’ll have no say,’” he says. “I was always glad it wasn’t too big.”

Instead, Bonner pursued art, at which he’d always excelled, attending Baltimore Junior College. One of his instructors, a commercial artist, helped him land his first job, working for Evelyn Bodine, wife of Baltimore photographer Aubrey Bodine, at an illustration and design firm. After moving to an advertising agency as an art director, Bonner started working on TV commercials and knew he needed to get into film. He transitioned over to Eucalyptus Tree Studio, where he did artwork and film. But he discovered that ad agencies sought out film companies, not design firms, to create commercials. Still, he made the best of it, and had fun.

One enjoyable project was a commercial for the Baltimore Zoo. He recorded the voices of his children and their friends saying how much they liked the animals. The visuals showed adults riding the zoo train with voice-overs from the children, including one who asks, “What are those monkeys doing?” “Of course, you know what those monkeys are doing,” Bonner says, implying that they were mating. The tagline was “The Baltimore Zoo—for kids of all ages.” The commercial won a New York Art Directors Club gold medal.

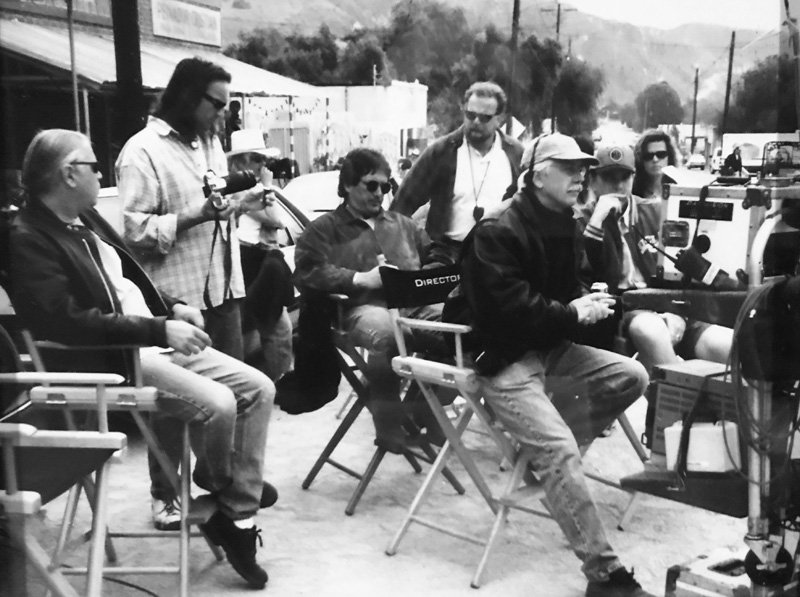

Bonner learned writing and directing by watching directors to see how they did things and staying open to the crews’ suggestions. Along the way, he worked with Garrett Brown, who later invented the Steadicam and Skycam, as a cameraman whenever he could, while Bonner directed. Once he had high-caliber contacts, Bonner launched his own company, Bonner Films.

His brother in-law is screenwriter and director Barry Levinson, known for films Diner, Avalon, and Rain Man, and Bonner often worked with Levinson’s wife, Diana, when she freelanced as a wardrobe, hair, and makeup artist. He married her sister Denise. Through Diana, he got into episodic television work, including directing a few episodes of the Baltimore–based series Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Bonner brought to his work an innate ability to visualize, something that he says a lot of directors don’t have; to compensate, they’ll shoot from every angle and then edit for the best. But he could imagine what he wanted—close to this subject, pan over to that one, and be finished—and in a business where saving time means saving money, that ability was platinum. In Los Angeles, while working on The Practice, Bonner was asked to finish filming in 15 hours, but he would wrap up work in 12 hours, so the crew could enjoy their evening—everyone was ecstatic.

Over time, Bonner became tired of episodic television. “The producers would totally let the directors do what they wanted, then change it,” he says. His own efforts to get producers on the same page with him were unsuccessful. Nonetheless, he enjoyed meeting and working with the actors.

Bonner lived through the drastic technological changes in the way moving images are recorded. He used to schlep 10 cans of 35-millimeter film, each 2 inches thick and 16 inches in diameter, to Technicolor in New York for processing. “Now, you take a teeny chip the size of your finger, copy all of it, erase it, and use it again,” he says. He shot footage with his iPhone for some commercial work, though he used a Panasonic mic to capture the sound.

He would like to do a remake of 21 Eyes, which he cowrote with Sean Paul Murphy in 2003, but the costs are prohibitive. His creative drives remain, and to satisfy them, he’s taken up woodworking. Among other projects, he crafted a set of child-sized Adirondack chairs for his grandchildren at his home workshop in Annapolis. “There are always things to do around the house and for other people,” he says with a smile, “but it ain’t filmmaking, by any stretch!” █