+ By MacDuff Perkins + Photos by Kirsten Anatone

When Michael Caimona was a teenager, a car accident left him with physical and emotional scars. During his recovery, he was introduced to the healing powers of music. He learned slow breathing, how to listen to music to calm nerves and anxiety, and how he could choose music based on how he wanted to feel. Music was used to complement the demands of his physical therapy practices to help regain his strength.

A decade later, Caimona found himself coming out of the military after multiple deployments. His appreciation for music had not only endured but also strengthened over the years, and, while working as a defense contractor, he started a side business building drum sets. Being a part of the music industry—seeing shows, connecting with musicians, and playing music—helped his transition from military to civilian life. But he didn’t leave his military experience behind.

“Friends who were in the military asked to come to my workshop,” says Caimona. Together, they’d jam on instruments or listen to music while he worked. “This was not music therapy per se, but they felt like they could get their hands dirty and keep their minds on something else. It was an outlet where you had fun and made connections.”

Those connections inspired Caimona. He understood, and had experienced firsthand, that the act of listening to and playing music was beneficial for healing. Within his own community, he saw the need for healing; he had lost friends to suicide and knew that the effects of trauma ran deep within the veteran community. He wondered if he could get vets to sign up for music therapy.

“I kept thinking, ‘I really think I’m sitting on a solution here,’” he says. “I had access to musicians because I had been supporting them through my drum business. If I could team veterans up with music therapists and musicians, a lot of cool things could happen.”

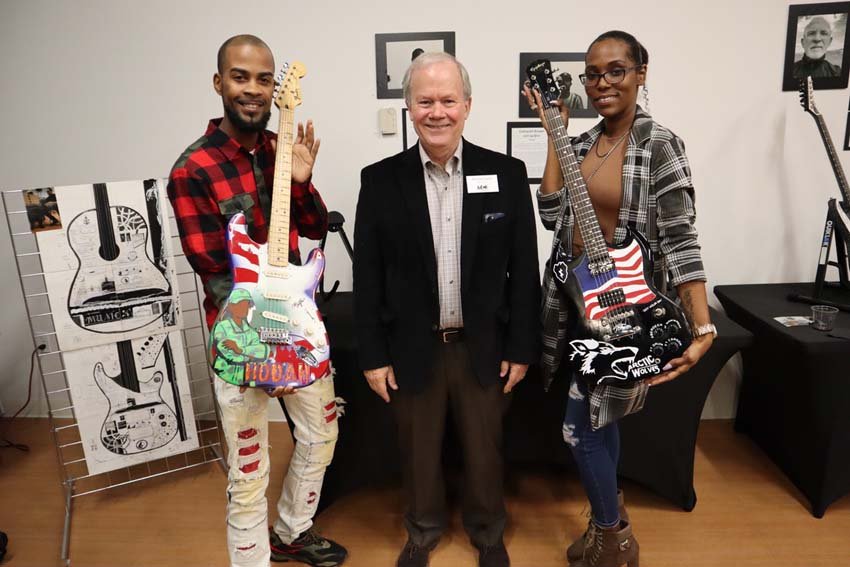

This sparked the beginning of Warrior Music Foundation (WMF), a nonprofit organization that helps pair veterans with music therapists and musicians and results in life-changing outcomes. A veteran signs up for 12 weeks of music lessons. The curriculum is designed by music therapists, allowing for an understanding of chord structure as well as emotional awareness. During the first meeting, a music therapist meets with the student. Stories are shared, and the camaraderie allows the teacher to discuss musical as well as personal goals and tailor the curriculum to the student’s needs.

For veterans and their dependents, the biggest personal goal is the understanding and relief of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The condition manifests uniquely in each person. There is no single formula for treating those with PTSD, and untreated, it can have long-lasting, harmful effects. The most significant harm untreated PTSD can give rise to is self-harm. A 2021 study by the Costs of War Project found that since 9/11, four times as many service members and veterans have died by suicide as have perished in combat. Today, that equates to between 40 and 44 veterans and service members dying each day due to suicide and self-injury.

Telegraphing a person’s intent to self-harm is essentially impossible. But it is possible to study the symptoms that frequently predate episodes of self-harm. So, when music therapists and music instructors with WMF work with veterans, they start by communicating about how the student is feeling. “Depression, anxiety, and sleep deprivation are leading indicators for self-harm,” says Kirsten Anatone, director of programs for WMF and a music therapist. “We speak to them during their lessons and gauge what their needs are, based on their symptoms. PTSD disrupts the neural pathways due to physical damage in the brain. But since music is both a right- and left-brain activity, we can use it to remap the neural pathways to get around the damaged areas of the brain.”

The lessons are not just for PTSD. Any veteran who wants to take music lessons is welcome in the program. “It lets you know how just badass vets are,” says Caimona. “When a double amputee comes in and says, ‘I want to learn how to play the drums,’ we just say, ‘Let’s do it.’”

That these lessons—and the therapy—happen in music stores is the real magic of it. Therapists and instructors meet their students where they are comfortable, in a safe environment. Light discussion leads into good conversations about life. There is connection and reconnection. By learning to play an instrument and to listen deeply to music, the student is given a tool to alleviate suffering stemming from combat-related trauma.

As in any therapeutic modality, however, getting the student to the teacher is often the biggest hurdle. To combat this, WMF focuses on the whole family. “Often, it’s the kid who wants the lessons,” says Caimona, who understands that family members will often suffer through a secondary traumatization. For a child, having a parent on deployment can be enough of a destabilization to create an issue at home. Sometimes there are symptoms—an eating disorder, disrupted sleep patterns, or acting out—but often it’s just a matter of giving the children a creative outlet. “We’ll get the kid the guitar lessons, and they’ll get Dad to do it with them,” says Caimona. “That’s when we can get to him, get him the support he needs. It’s our goal to keep families together.”

One such father is Matt Tabar, a chemical engineer who spent 20 years as a naval aviator and navigator for the navy. He had dabbled with music as a teen but never developed the discipline to practice. “I always enjoyed the analytical aspects of music, how chords play together, and how songs are constructed,” he says. Tabar met Lee Priddy during a musical festival held on the base with some children that Priddy was instructing. As homeschooling parents, Tabar and his wife were interested in getting lessons for their children. Priddy connected Tabar with WMF and offered to instruct the children and Tabar himself.

“My initial intention was to get music lessons for two of my sons,” says Tabar. But he was also curious about several of the other WMF offerings—the weekend songwriting retreats and music events in particular. He started studying guitar with Priddy and found that the experience of learning to play an instrument allowed him to begin to process experiences in a way that felt healthy and healing. “Music is an emotional experience,” he says. “It gives words to why and how experiences can be more valuable. I’ve always been an analytical person, and music therapy has codified the emotional connection of songs.”

For Tabar, the experience of learning to play an instrument allowed him to begin to process experiences in a way that felt healthy and healing. Tabar experienced combat-related trauma but was also able to examine his own life experiences in an insightful way. “One thing we’ve discussed is how you can allow music to direct emotional processing,” he says. “Music is a control for me, and I can use it to transition to something calmer or more productive. I can use it to mood shape. If I’m in one state and know that I need to get to a different state, I can use music intentionally to walk me through.”

Using musical mnemonics to process and express information works in many ways. For veterans who have suffered traumatic brain injuries or memory loss, learning a melody can help them recall important aspects of their lives that may have been lost. Other times, life experiences can warp a sense of self and distort the person’s understanding of who they really are. “Often, veterans move out of the military and struggle to integrate back into society,” says Anatone. “Music is such a great tool for expression, and music therapy assists in the reconstruction of the identity of the self.”

Tabar works with Lee Priddy to learn songs but also uses lyrical analysis and listening sessions to understand how to effectively process complex emotions. “We’ll play through a song, and he’ll say, ‘What lyrics jump out at you?’ And then you let your subconscious guide you. There will be acute moments of understanding, and we’ll identify themes to what I’m feeling and experiencing,” says Tabar. “In terms of long-term processing, I now have music as a tool to help me.”

Lyrical analysis was once more of a side project within WMF’s curriculum, but it has since become the foundation’s core. Songwriting retreats gather veterans and professional songwriters for a weekend of storytelling. By exploring their lives, their influences, and their inspirations, the veterans act as a muse for the songwriters. Group sessions allow everyone to share stories and make friends. At the end of the weekend, a vet and a songwriter create a song that tells a story of personal experience. “It’s just wild to spend a weekend getting to know someone, and then walk away with a three-minute song about your life,” says Tabar. “It’s one of the most impactful things you’ll go through,” says Caimona. “It’s life-changing for everyone involved.”

While Caimona is amazed at the amount of benefit that WMF has already brought to the community, he also feels a great pressure to help as many vets as possible. “We have all the support we could possibly want,” he says. “What we don’t have is funding. We have the studios and the volunteers, but what we need is the community to realize that, just in this area, we have a huge population of veterans who need support. People think that just because we don’t have troops in Afghanistan, we don’t have problems anymore. But we do.”

Due to the generosity of the music teachers, one veteran can receive an entire semester of lessons for just $500. Currently, WMF has a waiting list of roughly 300 local veterans. █

For more information, visit warriormusicfoundation.org.