+ By Julia Gibb

After Kamajian and I greet each other outside of Zü Coffee in Gambrills, he ducks inside to get himself a hot tea as I wait in the outdoor café. The evening is mild but turbulent, the full moon glancing occasionally through scudding clouds. The artist’s appearance causes a stir in the gaggle of young vape-ers gathered near the entrance. I try to eavesdrop. “[Mumble mumble] Kamajian . . . yeah, he comes here sometimes,” is about all I get. It’s as if we’re all being treated to an encounter with an elusive, but affable, nocturnal creature in an unlikely suburban habitat. Over the next few hours, Kamajian reveals that he, like the subjects of some of his paintings, begins to come alive at night.

After Kamajian and I greet each other outside of Zü Coffee in Gambrills, he ducks inside to get himself a hot tea as I wait in the outdoor café. The evening is mild but turbulent, the full moon glancing occasionally through scudding clouds. The artist’s appearance causes a stir in the gaggle of young vape-ers gathered near the entrance. I try to eavesdrop. “[Mumble mumble] Kamajian . . . yeah, he comes here sometimes,” is about all I get. It’s as if we’re all being treated to an encounter with an elusive, but affable, nocturnal creature in an unlikely suburban habitat. Over the next few hours, Kamajian reveals that he, like the subjects of some of his paintings, begins to come alive at night.

Though the mononymous artist describes himself as a private person, he slips easily into conversation, discussing his Armenian heritage, military brat childhood, and lifelong attraction to all things dark and creepy—monsters, vampires, and spiders have always captured his imagination. At an early age, Kamajian had a keen interest in art, music, and science. When he received toys as a child, he was more fascinated by the images printed on the packaging than by their contents. He coaxed rhythms out of everyday objects, using pencils as drumsticks. While his aptitude in science led him to consider a career in medicine, he ultimately decided to attend Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where he studied illustration and fine art.

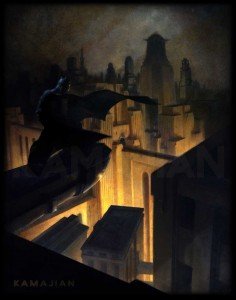

Oil painting, computer graphics, digital three-dimensional modeling and animation, and sometimes photography, are the mediums for Kamajian’s visual art. Over the years, he has produced pieces for DC Comics’ Batman series, the cover art for Jimmie’s Chicken Shack’s album re.present, and scientific illustrations, along with the oil paintings and digital images he produces for his own creative fulfillment. Those familiar with German expressionist film, film noir, and the mythology of Batman’s Gotham City will easily recognize those themes in his visual works. Using the Old Master technique of chiaroscuro, Kamajian carves cityscapes out of darkness; skyscrapers with Art Deco features tower like petrified shafts of light, and industrial elements intermingle with the human form. Monochromatic hues and chiseled physiques give figures a gritty, monolithic presence, while strong diagonals lead the eye around his compositions.

Oil painting, computer graphics, digital three-dimensional modeling and animation, and sometimes photography, are the mediums for Kamajian’s visual art. Over the years, he has produced pieces for DC Comics’ Batman series, the cover art for Jimmie’s Chicken Shack’s album re.present, and scientific illustrations, along with the oil paintings and digital images he produces for his own creative fulfillment. Those familiar with German expressionist film, film noir, and the mythology of Batman’s Gotham City will easily recognize those themes in his visual works. Using the Old Master technique of chiaroscuro, Kamajian carves cityscapes out of darkness; skyscrapers with Art Deco features tower like petrified shafts of light, and industrial elements intermingle with the human form. Monochromatic hues and chiseled physiques give figures a gritty, monolithic presence, while strong diagonals lead the eye around his compositions.

Kamajian’s affinity for the Batman character comes from the superhero’s lack of superpowers. Fully human, motivated by his childhood trauma to devotedly fight crime, Batman relentlessly hones his mind and body, seeking knowledge, studying martial arts, and always adding new arrows to his crime-fighting quiver. For Kamajian, anybody who has had a transformative experience, especially artists, might relate to this character. To capture Batman’s dark urban environment, he explains, “I imagine I’m an artist in Gotham City, and I paint it the way I would paint it if that was my world.”

Drumming features prominently in Kamajian’s life. Weekdays start in the afternoon, with a therapeutic hour or so on the kit. This mentally and physically prepares him for his day. He also sits in with various bands—most recently with the gypsy music band Balti Mare—and plays hand drums along with tribal house music at local clubs. Moving people literally and figuratively is his goal, using ultraviolet-reactive bongos and other hand drums that glow under black light, adding an eerie visual element to the percussive experience. Fascinated by all things glow-in-the dark, he recalls a night at the beach in which a storm had deposited bioluminescent organisms in the sand. “When you would step on the sand, and lift your foot up, it would sparkle,” he marvels. ”Where there were tide pools, they were just full of stuff that was glowing in the dark.”

The two of us repair to Kamajian’s nearby home, where I view some of his paintings. His easel, which he moves to different rooms depending on his mood, is currently in a shadowy corner of his den so he can work in the company of his favorite black-and-white movies. He pulls out some paintings on Masonite panels— dappled layers of glazes shine with gloss varnish, creating a mysterious glow. They seem lit from within, as if by strange bioluminescence shimmering through murky waters. He directs me back to his easel and criticizes the work there for being too polished. As with his drumming, his focus is more on eliciting an emotional reaction, and less on technical prowess.

The two of us repair to Kamajian’s nearby home, where I view some of his paintings. His easel, which he moves to different rooms depending on his mood, is currently in a shadowy corner of his den so he can work in the company of his favorite black-and-white movies. He pulls out some paintings on Masonite panels— dappled layers of glazes shine with gloss varnish, creating a mysterious glow. They seem lit from within, as if by strange bioluminescence shimmering through murky waters. He directs me back to his easel and criticizes the work there for being too polished. As with his drumming, his focus is more on eliciting an emotional reaction, and less on technical prowess.

Kamajian rarely participates in gallery exhibits or sells his paintings. His involvement in fine art is driven by his passion for it. Drumming, too, has a soul-nourishing effect on him, as does the yoga and meditation he practices. We swap stories about the patched-together kinds of lives we lead, working multiple part-time gigs, and I ask if it is ever difficult for him. Kamajian pauses, smiling wryly, and fixes me in his startlingly lucent gaze. “You know the answer to this: it doesn’t matter, as long as you love what you are doing.” And as he strives in his work to transcend technical proficiency, the moral of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, one of Kamajian’s favorite German expressionist films, seems to ring true of art as well as life: “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart!”