+ By Terese Schlachter + Photos courtesy of Joanne Bond

Joanne Bond is a prolific ex-scrape artist. When in a bind, she literally creates her way out. Broken heart? Put the pieces back together in a collage. Illness? Draw it out with a medicinal cocktail of color. Husband dies in the bed next to you (but then comes back to life)? Crochet healing blankets for the masses. Spend a decade in a cult? Okay, that one is a little more complex, but in the end, the piano saved her.

“I wanted to be an art therapist,” says Bond of her early years as an artist searching for a college major that would be more palatable to her father than simply “art.” Then, just as her artwork was gaining some recognition, love took her in another direction.

It was the late 1970s, and Fleet—a tall, dark, and earnestly spiritual man—was her world. She’d loved him since she was 14, so when he decided to join the Hare Krishnas, she went, too, moving into the group’s temple in Potomac, Maryland. Her days began at 4 a.m. with ritual chants and dancing before statues of the deities. Later, there was cooking and cleaning. Rules in the temple kept men and women separate unless they married, so Bond and Fleet got engaged. Then Fleet’s mother stepped in.

“She said she was taking him for a haircut,” recalls Bond, “and I said to him, ‘You’re going to shave your head anyway . . .’” As it turned out, his mother had a deprogrammer (a person who uses confrontation or other more forceful tactics to eliminate a belief or attachment) sitting in a van, waiting for him. That was followed by a deprogramming camp in Minnesota. Fleet never returned.

“I was so in love with him. He was whisked away,” says Bond. The unattended open wound would fester for years. With no social or economic means on the outside, she remained in the cult for the next decade. The Krishnas arranged a marriage to a man who turned out to be abusive and with whom she had two children. Her only artistic outlet was Krishna-related design and song. After she was able to leave the cult, with the support of friends, she got a job as a typesetter, eventually launched her own graphic design company, remarried for a time, and had a third child. She later met up with a Hare Krishna teacher on the outside who led her back in. When that man was accused of swindling his followers, Bond broke free for good. “When you leave a cult, there is guilt and a lot of self-criticism,” she says.

Then, some 20 years after he vanished, Fleet briefly reappeared, and he and Bond got together to talk about what happened. Days later, he sent her some old photos.“[They] brought everything back to me in a way I hadn’t expected,” she says. “I had to face that part of my life.” She sought refuge in the piano, obsessively playing and composing. The music was shadowy and mysterious, drawing on the tonal strains of Hare Krishna chants.

Friends talked the budding but stage-wary musician into performing at open mic nights in Baltimore. She connected with songwriter, guitarist, and producer Brad Allen, and together they created her first album, Joanne Juskus (her professional name), which released in 2001. The reviews were magnetic.

Bond and Allen related like siblings, traveling to performances in New York, Virginia Beach, and Annapolis, but their relationship was fraught with conflict and tension. She said that he was addictive and erratic, sometimes ditching performances or showing up drunk and abusive. They parted ways, and Bond spent the next decade pursuing her own musical interests, performing and releasing another album. She had begun a music series in Baltimore, and when the Creative Alliance purchased the Patterson, a theater space, she took her series there. Enter Ian Hesford and Jason Sage, whom she invited to the Patterson as an opening act. Coincidentally, the two were searching for someone who sang mantras, and the psychedelic world music band Telesma was born.

“I’d been in a really rigid situation,” says Bond. “The experience with Telesma just opened me up.” As lead singer, she recaptured elements of her so-called lost decade, making good on the influences of the Hare Krishna. She wore saris and gopi dots, which, for the Hare Krishnas, mark the body as a temple, protecting it from evil influences. For Bond, it was more of a cool tribute costume, and it all played into the hypnotic theme of the music.

Telesma became Baltimore’s house band, playing at places such as Rams Head Live and the Hard Rock Cafe. Music consumed Bond’s life. She had to let go of some of her graphics business clients to make time for her musical success. Telesma is a partnership that’s lasted for more than 20 years.

In 2006, an opening act once again created another opening—this time of her heart. Adrian Bond, an electric guitarist and composer, showed up to fill in one night at the Avalon Theatre in Easton, when she was asked to perform but her regular guitarist wasn’t available. He crammed, learning all her songs, only to have the performance canceled. Not wanting to waste all that effort, they teamed up to perform at Annapolis’ 49 West Coffeehouse, Winebar & Gallery to a sold-out crowd. They called themselves pillowbook, playing mostly Celtic and English folk music to local audiences. Meantime, the couple’s musical partnership bloomed into a romance. They made a home together in Eastport.

One night in November 2012, Adrian rolled over onto Bond’s pillow, his eyes open and glazed. “I could tell he was dead,” she recalls calmly. She’d had a similar experience when one of her Telesma bandmates collapsed on stage just seven months earlier; he survived after doctors packed him in ice. She called 9-1-1, and the operator talked her through CPR until an ambulance arrived and dollied him away to an arctic recovery. The ice worked, and Adrian came home, mostly unscathed. They both quit smoking.

With her now idle cigarette-free hands, she began crocheting, wrapping friends and relatives in well-spun yarns. “I must have made 50 afghans and dozens of hats,” she laughs. She gripped the needles forcefully enough to eventually cause carpel tunnel and trigger thumb. Luckily, painting requires a lighter touch, as does a pen.

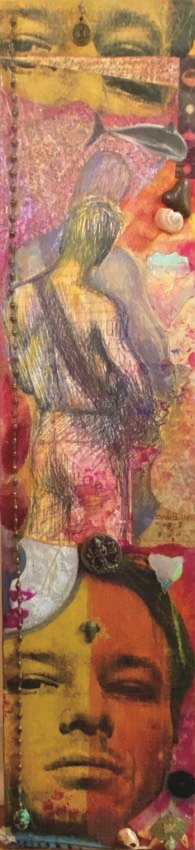

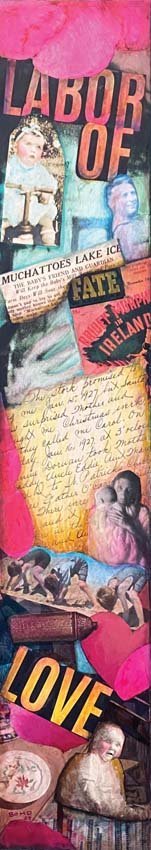

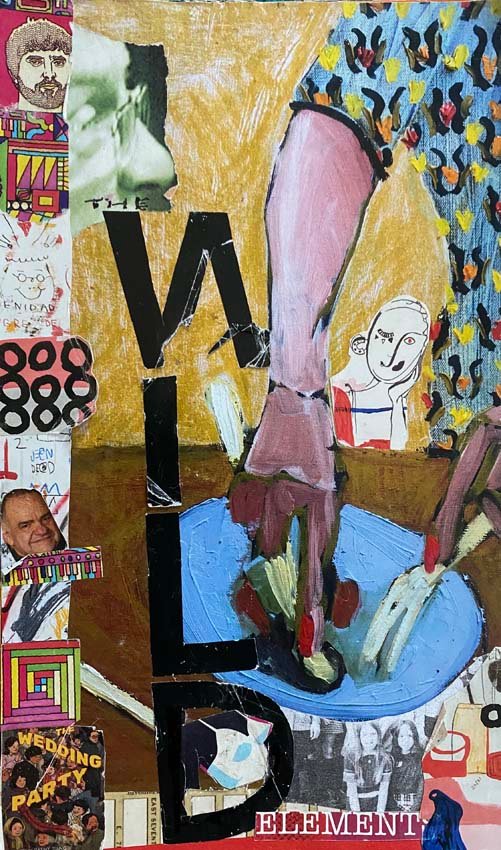

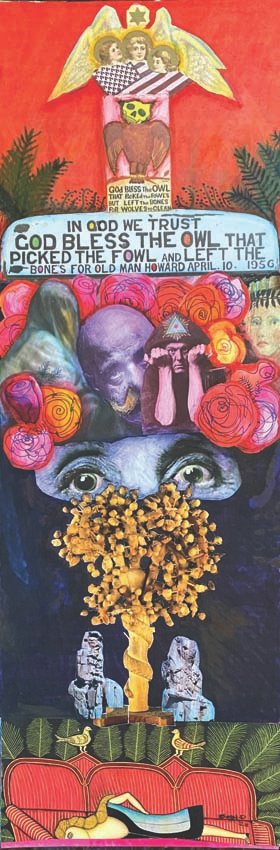

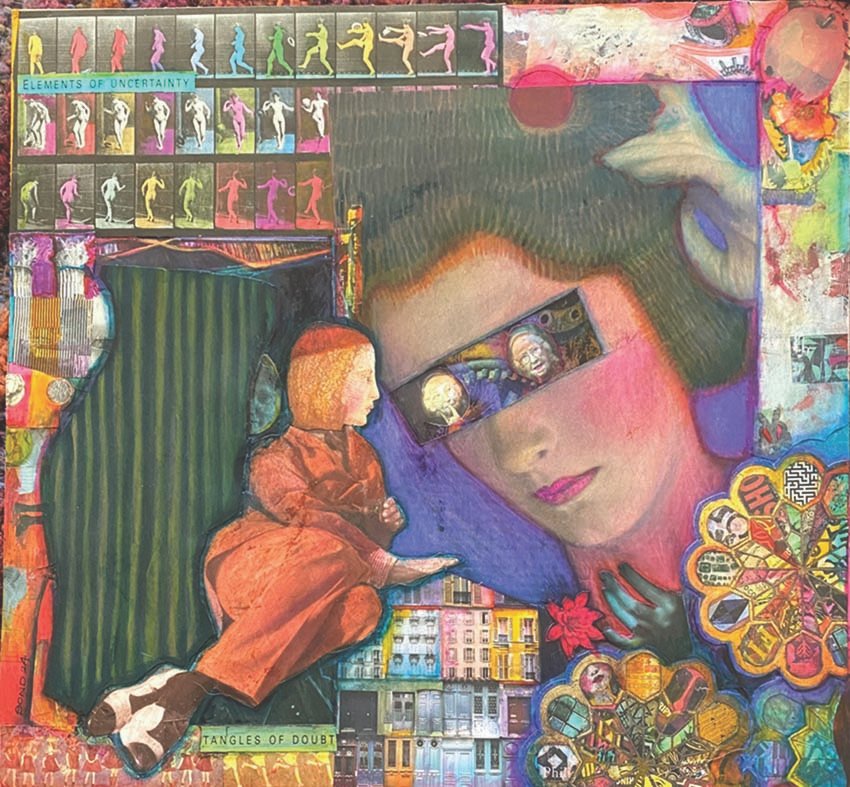

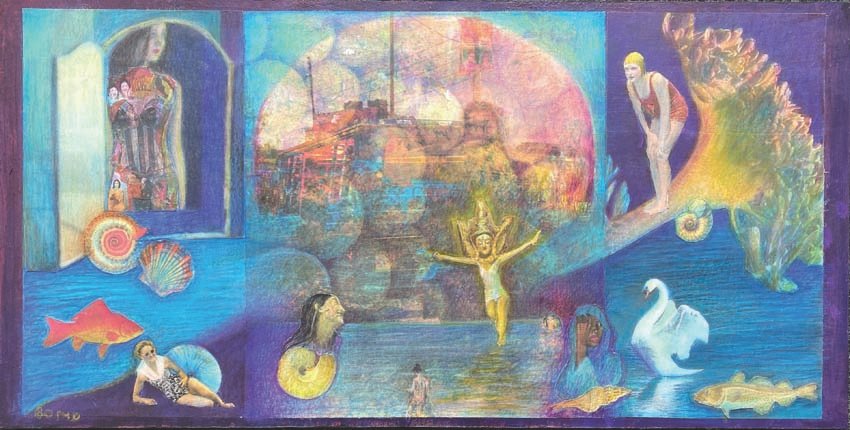

Stacks of journals she’d been filling since childhood now beckoned. She’d designed covers for many of them, collaging artifacts from her life. The notebooks would provide great material for a memoir, she thought. And so, the dig began. She wasn’t prepared for what she unearthed—pages and pages of outpourings, including some gut-wrenching passages about Allen. “I just couldn’t deal with the emotion,” she says. So she went back to the palette, working to piece together what had fallen apart. Allen began appearing in her collage, a haunting face peering between strips of color, like blinds on a window.

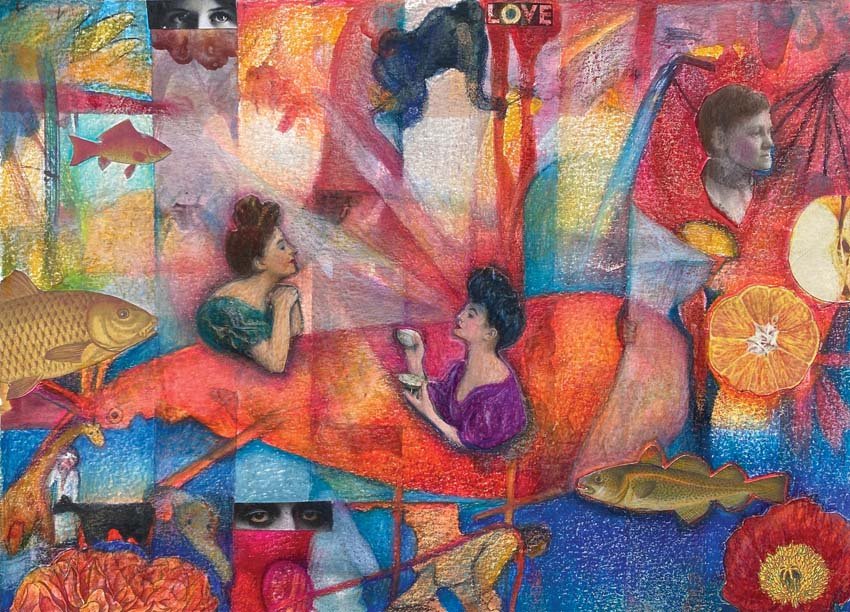

“I realized I never dealt with him, our split,” she says. Beautiful dark elements portray Allen while pieces of her childhood also dot the work; chunks from her mother’s baby book and paper dolls cut from old family photos and photography books loom curiously through the pieces. “Music, art, writing I turn to when I don’t know what I want to express,” she says. “It’s a medium to carry your emotion.”

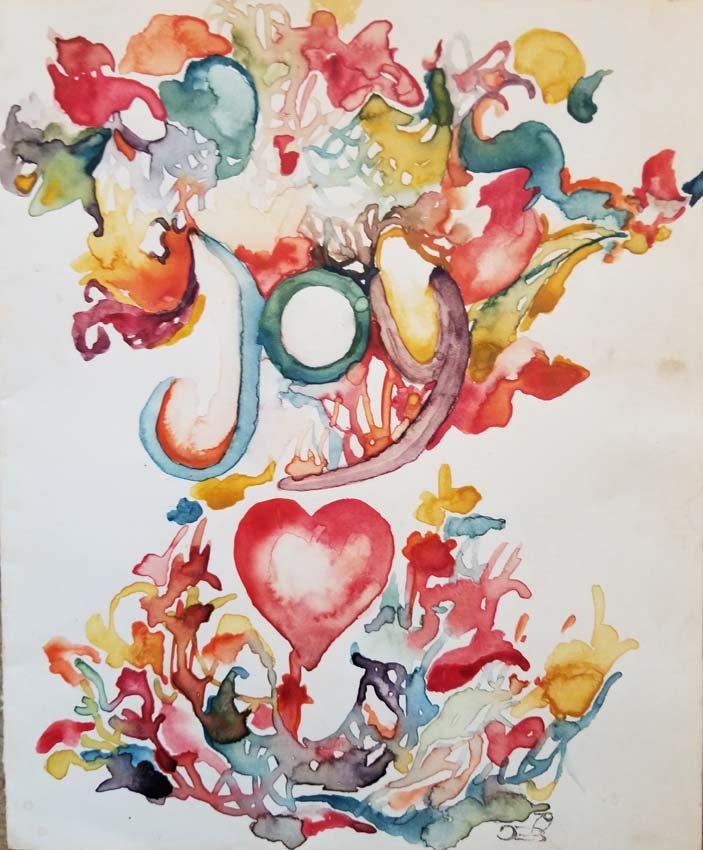

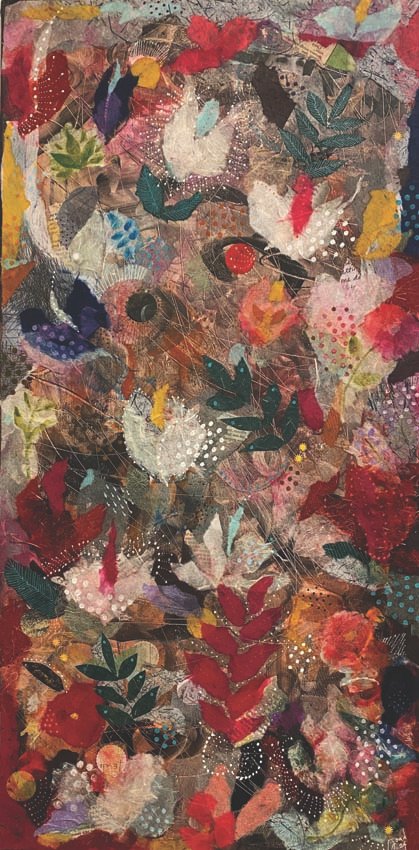

In 2015, Bond was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease that left her often bedridden. Performing seemed unrealistic, but she could paint. She was, once again, in a dark place, seeking light. She tried leaving more space between the colors of her work, to brighten it. She chose pastel-colored tissue paper as her medium, crocheting with color, sometimes crayon, and textured mulberry paper.

“I like looking at light coming through things,” she muses, grazing a blank paper with pencil to warm up. Her current work explodes with color and florals, but there are also notes of cleansing, the hint of a guitar, and an occasional Buddha. It’s psychedelic, like the band, warm like a colorful blanket, and, not surprisingly, healing.

In May, light will shine from and upon Bond’s work in her debut exhibit with Art Down, in Annapolis.

For more information

visit joannejuskus.com.

Chris Mandra, Ian Hesford, Bond, Jason Sage, Bryan “Jonesy” Jones and not pictured Mike Kirby. Photo by Theresa Keil