+ By Jennifer Kulynych

Holly Estrada has had a life. You see it in the eyes of the women she paints—enormous and expressive, eyes that have seen tragedy and disappointment but also joy. These are the eyes of real women with complicated histories.

Estrada conjures most of her subjects from her own imagination, but occasionally she paints from life, as she did in the portrait of her teenage daughter that hangs in the dining room of her Crownsville home. Against a backdrop of viridian fields and snow-covered blue mountains, Estrada’s daughter stares directly at you, neither smiling nor unhappy, wearing a black halter dress, arms bare, her auburn curls wrapped in a halo of flowers. The painting could be a romantic art nouveau illustration, one of the Alphonse Mucha images that Estrada admires, if only her daughter’s expression weren’t so uncompromising. To Estrada, this painting is personal, full of symbols representing the ideas that, at age 51, she now finds meaningful.

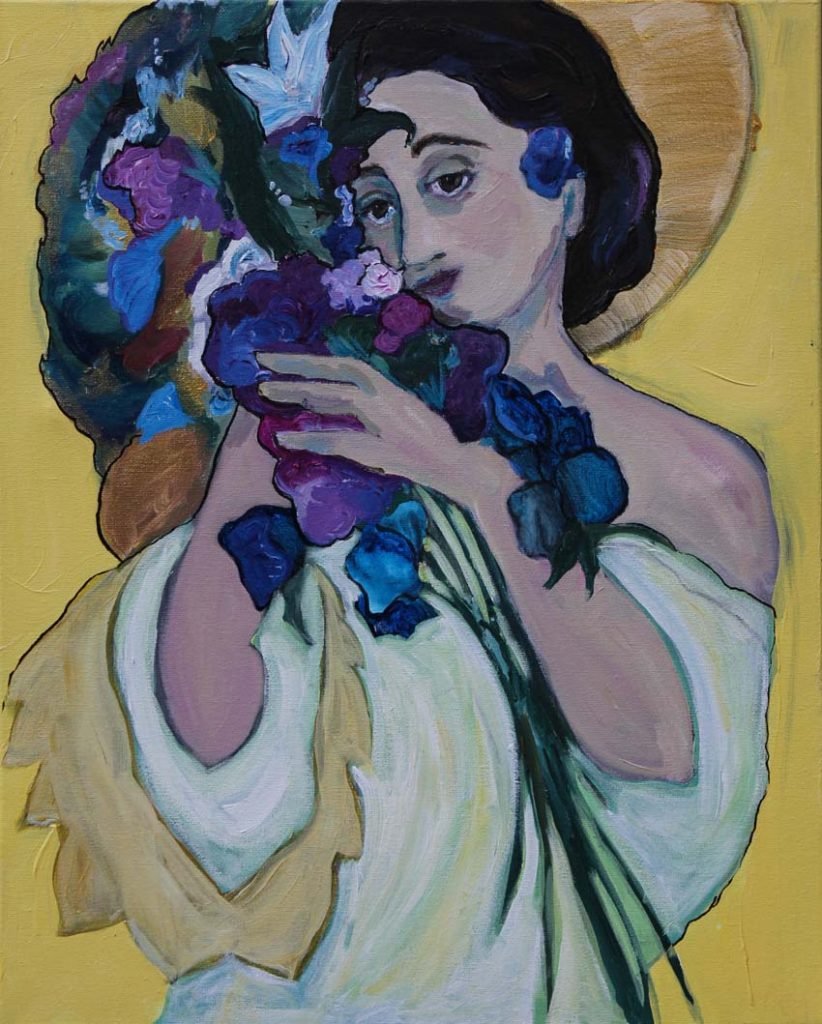

Halos, for example, are an important element in Estrada’s artistic lexicon. In various forms, halos appear in almost all her paintings. She’s inspired by medieval iconography, with its richly colored images of religious women framed by gilded halos. But to Estrada, the beautiful religious portraits lack something essential. “They’re flat,” she insists, “and missing feminine truth.” The truth she has in mind is the power that comes from a woman’s connection to both the natural and spiritual worlds. Her sensibility may be more supernatural than religious, as she aims to convey a certain life force. Estrada makes art that is, in her words, “a little bit pagan.”

Estrada’s ability to convey power and femininity through the eyes of her subjects real and imagined was recognized by other artists when, with the encouragement of friends and family (and still using her married name, Barrett), she entered a juried competition for an Arts Council of Anne Arundel County exhibition at Baltimore-Washington International Airport. Two of her paintings, White Maiden and Maid of Yellowstone, were selected for the council’s July 2018 exhibit titled “Beautiful America.” As a participating artist, Estrada also had the opportunity to meet juror, fellow artist, and Maryland’s First Lady Yumi Hogan.

Today Estrada sells most of her paintings to women, many of whom love to tell her what they see in her art. “I’ve found that I have a specific audience,” she says. “Women who see something wonderful in the images I paint, who love the power they see reflected there.” Working in acrylic and painting nearly life-sized images, she uses scale and bright color to make her subjects immediate and accessible. She paints women of all ages and ethnicities, with an aura of mystery. Yet Estrada wants her work to maintain an undeniable universality, so when painting facial features, and eyes especially, she is careful not to veer into portraiture.“I don’t want to get too tight or specific because you can lose something in that,” she explains.

Estrada’s path to becoming a working artist was long and meandering. Early on, as a student at Bates Middle School and then at Annapolis High School, art teachers urged her to develop her natural abilities, and she came to treasure the safe space that art created in her life. Yet after graduation, Estrada made what seemed the more practical choice: culinary school, then jobs, first as a line chef and eventually sous chef in the kitchens of several Baltimore restaurants. In Estrada’s memory, the restaurant world of the late 1980s was fast paced, high pressure, and testosterone charged. It became clear that cooking for a living wouldn’t involve making art through food. “Professional cooking is all about getting the product out,” she says.

She left cooking, got married, and raised two daughters and one son. Her world became all about meeting every expectation that our culture places on mothers: making meals, driving children to school and sports, continuously providing, preparing, and protecting. Estrada focused almost exclusively on being present in her young children’s lives, especially during a difficult divorce that she says happened quite suddenly, on the heels of her then-husband’s experience as a September 11th World Trade Center survivor. Making art took a back seat until her children were older.

Later, while pursuing a master’s degree in art education, Estrada had the opportunity to study in Mexico, where she fell under the spell of feminist icon and famous early twentieth-century Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Kahlo’s jewel-toned palette and the symbolism of Mexican folk art are visible everywhere in Estrada’s current work.

With her black hair and bright smile, embroidered white peasant blouse, and red lipstick, Estrada herself evokes a sunnier version of Kahlo, and Estrada happily acknowledges the artist’s influence. When Estrada learned that Kahlo, who suffered from chronic pain, often painted in bed, Estrada decided to give it a try. She now keeps an easel at her bedside for those moments when she wakes up feeling inspired to paint, which happens often, these days.

Happily remarried, Estrada now divides her time between creating her own art and teaching art to students at Southern Middle School. She has long been an art educator, but feels her career as an professional artist has just begun to blossom. Excited by this new development, she credits her own, very personal epiphany. “It was scary to put myself out there,” she admits, “but I stopped making art for other people and told what was going on inside myself.” █

To learn more about

Holly Estrada’s art, visit

www.hollyestradaartist.com.

“Goddess of Yellowstone” Acryllic Painting on Canvas

“Goddess of Late Summer” Acryllic Painting on Canvas

“Goddess of Summer” Acryllic Painting on Canvas

“Weary Soul” Acryllic Painting on Canvas

“Madonna and Child” Acryllic Painting on Canvas

“Hunter” Acryllic Painting on Canvas

Artist, Holly Estrada preps her paint palette in her home studio. Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Artist, Holly Estrada works on a painting in her home studio in Crownsville, Maryland Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Artist, Holly Estrada works on a painting in her home studio in Crownsville, Maryland Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Artist, Holly Estrada works on a painting from her bed in her home studio in Crownsville, Maryland. Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Artist, Holly Estrada works on a painting from her bed in her home studio in Crownsville, Maryland. Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Painter, Holly Estrada in her backyard in Crownsville, Maryland. Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Artist Holly Estrada holds two of her paintings, “Reflection” and “Third Eye” Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Artist, Holly Estrada hangs one of her paintings in her personal gallery outside of her home studio. Photo by Emily Larson (Fearless Photography Mentorship)

Holly Estrada (center) with her late mother and Maryland’s First Lady, Yumi Hogan, at the July 2018 Arts Council of Anne Arundel County Exhibition. Photo courtesy of Holly Estrada.