+ By Terese Schlachter

Stacey Turner works on whim, disciplined only by instinct. Vagary provides the modus operandi. An urge becomes the path. She may not know the route—or even the destination. But she knows that in the end, she’ll get there.

“I used to say I’m a bumblebee—they aren’t built for flight,” says Turner. Indeed, it’s long been considered a miracle of nature that the insect’s robust constitution is kept airborne by its tiny wings. “But they don’t know they can’t fly. So, they fly. That’s me. I don’t know what I can’t do.”

Turner first spread her nascent wings as a child in North Carolina, drawing, painting by number, decorating pottery, trying her small hand at pointillism—applying dots of color that blend to form an image. There was none of the usual youthful pondering over her future, what she wanted to be when she grew up. Turner, and her parents, always assumed that she would be an artist.

The Art Institute of Philadelphia beckoned, so she headed north. “I had all my stuff; I looked around Center City and got an apartment that afternoon,” she recalls. She spent the next week exploring the urban landscape, finally noticing a “Help Wanted” sign in the window of the Society Hill Hotel at Chestnut and South Third Streets. “It was a Saturday,” she says. “They said, ‘We need you tonight.’” She tended bar there for three years, working her way through school.

She met her partner at a wedding. They wound up settling in Annapolis and had a girl and then two boys. “I would be excitedly teaching my kids what I knew [about art], thinking, ‘Every kid should know this.’” One day, as she was walking her daughter Olivia to kindergarten, she came upon a “For Rent” sign in a vacant storefront space where Cornhill and Fleet Streets meet. Once again, a seemingly random window sign opened a door. There, she opened Already Artists, a studio for children.

Her mission was to engage youngsters before they learned self-doubt. She nurtured that tendency in a child to believe in what they are doing, that their work is good, that they’re rock stars. A patron of self-love, Turner believes her job is to provide knowledge and skill that is unencumbered by subjectivity, free from canon. And she does that without much guidance for herself.

“For ten years, I taught every day with no lesson plan,” she says. Once, she handed out pencils but cut off the erasers and kept them. Students were allowed to erase their work, but only after explaining the reason for doing so. “I wanted it to be a positive erasing, coming from a love of their work, not fear,” she says. She wants them to experience their own truth. A student who has a lot of self-doubt will lean heavily on the eraser. Turner believes that acceptance of their own work, as is, builds confidence and ultimately builds resilience Each young student walks in with their own gifts, their own talents. They are already artists.

One day, a young woman named Alison Harbaugh came to the studio. She was on assignment as a photojournalist for the Capital Gazette, looking to do a story about the school. Harbaugh was so moved by Turner’s teaching philosophy that she asked for a job. So began a yearslong relationship.

Turner never worried about registrations or being able to pay the rent; the studio always filled. By the time she was raising her third child, Leo, she decided that she needed to cut back, so she shut down the studio and began teaching lessons out of her home. She thought she’d have more time for her own work, but the students kept coming.

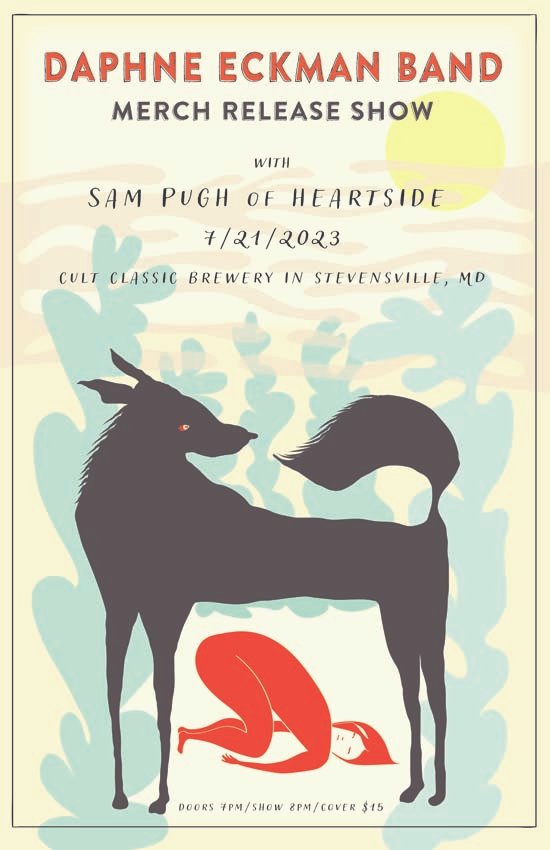

After a time, Harbaugh suggested opening another creative space, called ArtFarm Studios, that would allow for Turner’s children’s classes and Harbaugh’s photography workshops. In 2014, they started operations in a space on upper West Street. Turner left ArtFarm in 2017, and Harbaugh partnered with Darin Gilliam, which further expanded the studio’s mission. Turner says Gilliam’s arrival provided a seamless off-ramp. She was ready to be back on her own.

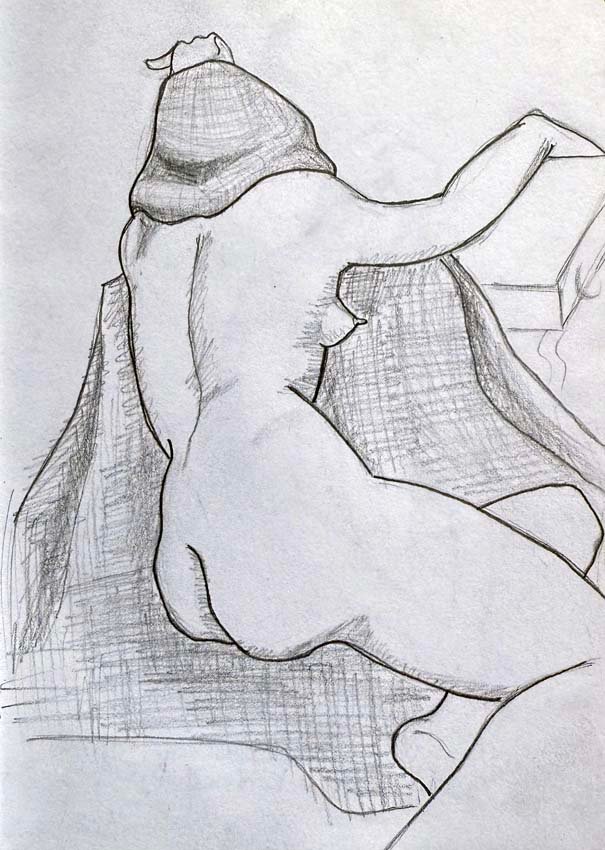

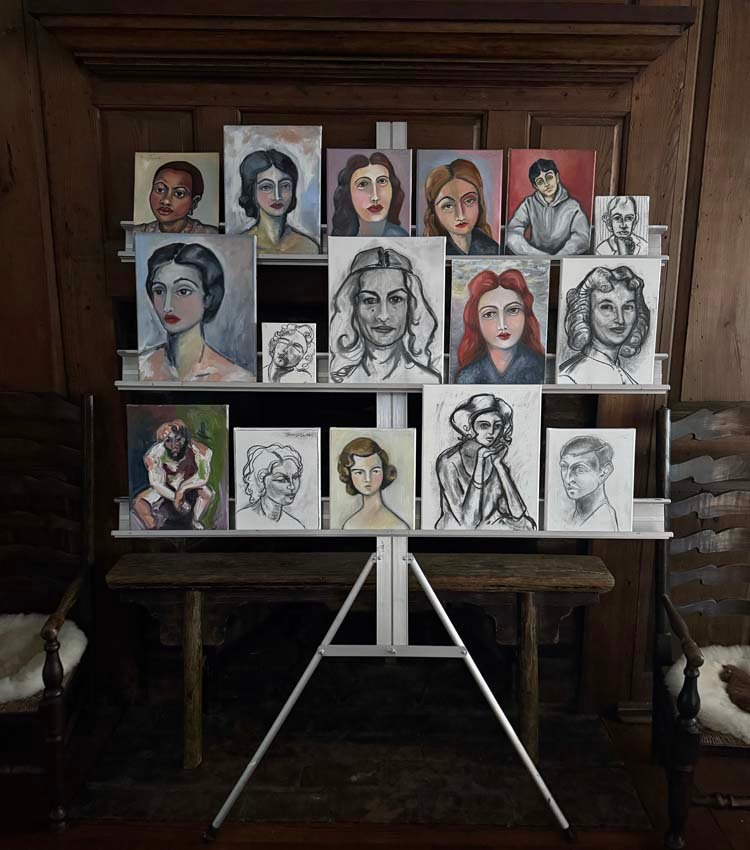

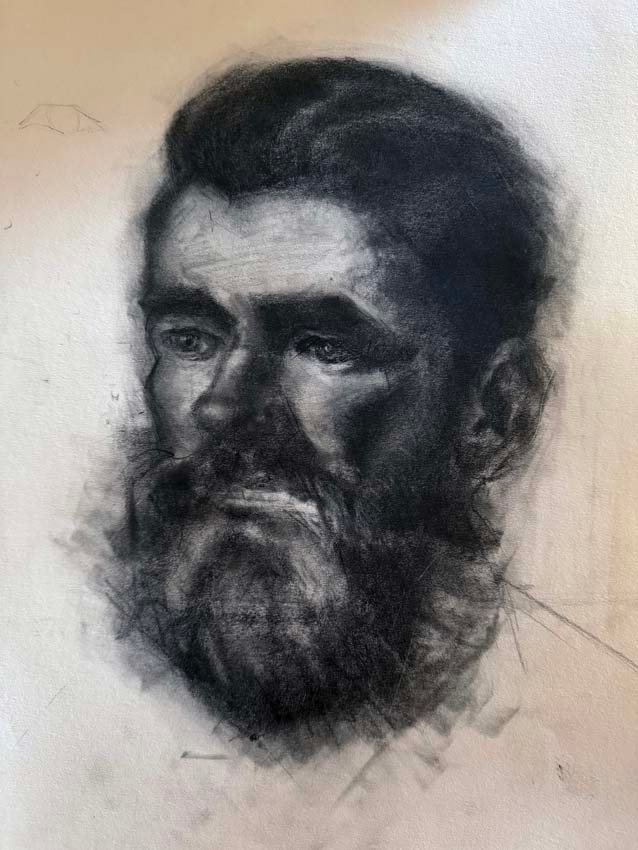

Turner paints and sculpts much in the same way she has lived. “Art is an extension of your movement,” she says. “You don’t know how it’s going to turn out . . . what it’s going to be until you’re done.” She often works with charcoal, creating portraits. “You get magical marks, and you don’t even know where it came from,” she says. “You couldn’t have done it better if you were trying. It just happens.”

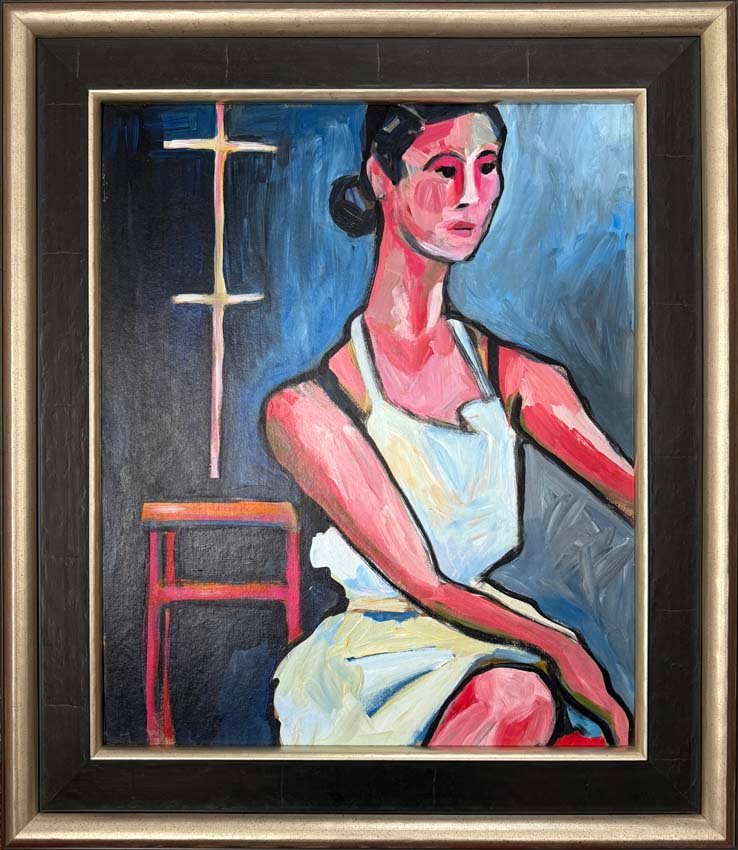

Alice Neel, a renowned portrait artist, once said, “You can do anything you will to do, if you’re sufficiently tenacious and interested; you can accomplish what you want to accomplish in this world.” Not surprisingly, she’s high up on Turner’s list of twentieth-century influences. Kees van Dongen, a portrait artist from the Netherlands who painted heavily almond-eyed portraits of women, shares space on that list, as does the more playful Maira Kalman. Neel is to Turner’s bumblebee as Kalman is to her whimsy.

Despite all the light and the children and the love in Turner’s life, there came a dark period, during the split with her partner. The turbulence came through in her work. Leo noticed it first, telling her, “Everyone you paint is you.” Turner says he was right—every portrait reflected her own concern, her own worry. She hid one of the tortured portraits away, literally closeting her disquiet. One client asked her for a light-hearted portrait, but Turner couldn’t pull it off.

People kept telling Turner that she needed a plan, that she needed to sort through things, pour a little concrete on her personal footpath. Her efforts only made things worse. “When people ask me for my three- to five-year plan, I get a wave of nausea.” She clings to winging it.

She says she’s now past the “accidental selfie” phase and is moving on to things more self-soothing. She’s thrilled to be working with artist Luke Hannam, whose works present as impulsive yet meditational. It’s the first time since school that she’s treated herself to a mentor. This fall, she’s teaching at Maryland Hall. At home, she creates commissioned portraits of people, children, and the occasional canine.

Recalling a visit to Paint the Revolution, an exhibit in Philadelphia, Turner experienced the modernist Mexican artists’ freedom from perfection. They were less than impeccable academically, some of the paint was overworked, perhaps a hand or foot was not anatomically correct, and some of the work even flowed out of its frame. “They didn’t go back and fix their mistakes,” she says. “That’s the ultimate in self-love, the next level of self-acceptance.” It made her cry. It was a lesson imperative for children, she thought, and for herself. She was already an artist. ν

For more information, visit staceyturnerart.com.