+ By Ellen Moyer

In his book Reverence for Life, German theologian Albert Schweitzer, describes how such reverence is the primary ethical foundation holding civilization together, and in 1952, he received a Nobel Prize for his humanitarianism based on that philosophy. But he was equally concerned by world conditions around him, convinced that, in war, humankind has lost the capacity to foresee and forestall and will end by destroying the earth.

In 1960, Greek architect and city planner Constantinos Doxiadis addressed the US Congress, expressing concern about our future quality of life in which issues of transportation, zoning, and communication are out of balance and population growth is ignored. He called for city planning that respected human scale and was park-like in design. As planner of the new capital of Pakistan, Islamabad, he had a model to demonstrate a city for the future, where cars and people were separated, roadways were broad and in forest-like settings, and where an abundance of green parks and forests dominated the cityscape. In this planned city, the influence and brilliance of Frederick Law Olmsted, father of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1898, had clearly taken root.

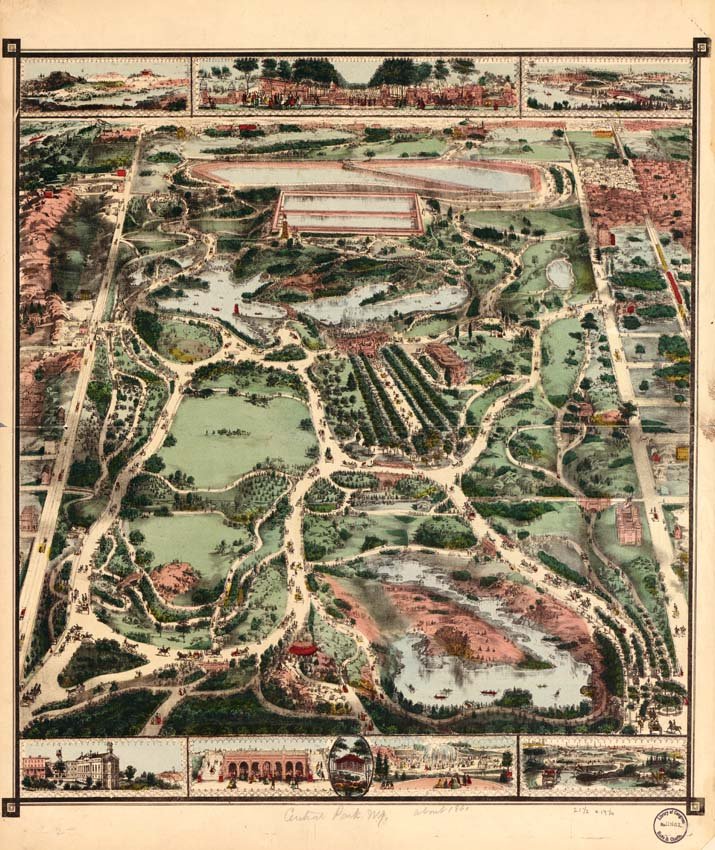

Olmsted was a man ahead of his times. Throughout the nineteenth century, he shaped our world so that we all might enjoy being outside without feeling attacked by our increasingly industrialized environment. In 1857, at age 35, he created New York City’s iconic Central Park. Continuing on professionally, he designed whole park systems for cities and influenced the creation of our National Park System, which serves to protect, preserve, and make America’s unique green cathedrals available to all her citizens.

Central Park, which was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in the 1850s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Parks, for Olmsted, were a commitment to egalitarian ideals and an essential part of a democratic society. His sons would take his vision further, setting high standards in constructing successful cities, towns, and neighborhoods with open spaces and landscapes that we admire today. The Olmsteds left their mark in a large way on America, and on our city in a small way.

Born in 1822, in urban Hartford, Connecticut, to parents who treasured nature and the outdoors, Olmsted was free to roam, hop, skip, and jump over hill and dale. He could explore anthills and frog ponds, build tree houses, and come home as dusk was descending. This enjoyment of natural, free play outdoors would stick with him throughout his life.

When poison sumac damaged his eyesight and ability to finish his application to Yale, Olmsted forfeited a college education. His first career took him to England, where, as a journalist, he visited public gardens and published a book about his experience. The New-York Daily Times (now the New York Times) commissioned him for a five-year research journey through the American South, resulting in three books that described the antebellum South. During the Civil War, Olmsted served as an administrator for the federal government, organizing medical services for the Union Army.

His love of the outdoors nourished and stabilized him as he traveled the impoverished South and worked during the war. It inspired him to team up with landscape architect Calvert Vaux to compete for the design for 843 acres on the then fringes of New York City in 1857. The multipurpose space they designed in Central Park included attractions for people of all ages and social backgrounds. It embodied his commitment to egalitarian ideals, chief among them the belief that common green space should be equally accessible to all.

From Hinrichs’ Guide to the Central Park, 1875. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Landscape was Olmsted’s art. Lakes, wooded slopes, lawns, forest-covered hills, and mountain and ocean views were his palette. The legacy he left is in the park systems he created before he died in 1903. Through his work, he ensured that the nation would be parklike and green, and he inspired Doxiadis, who would try to bring the greening of America to cities around the world. When visiting the Adirondacks, Biltmore Estate, Niagara Falls, and our National Parks, note the accentuation of natural habitat—Olmsted is there.

After his death, Olmsted’s sons continued in business until 1980. The creation of the National Park System and the road systems in the Great Smokies, Arcadia, and Yosemite felt their vision. They also made their mark in Maryland; Roland Park, Guilford, and Homeland—visioned and planned by Olmsted Brothers—are coveted places to live in Baltimore.

The Wardour neighborhood is greener and follows the topography, compared with the rest of West Annapolis.

Annapolis Roads.

In Annapolis, they were commissioned by the Giddings family, who had inherited 225 acres of land along the Severn River, to design a new neighborhood. The design followed the undulating topography, with winding roads, irregular lots, preservation of specimen trees, and community open spaces. Today, we know this area as Wardour—named after the English castle that was the birthplace of Anne Arundel, wife of the second Lord Baltimore, Cecil Calvert—which still looks much as envisioned 100 years ago.

Wardour is not the only Annapolis neighborhood designed by the Olmsteds. Nestled between Lake Ogleton (named after landowner Ben Ogle, Maryland’s governor in 1798) and the Chesapeake Bay, 341 acres would become the home of Reila Armstrong, wife of a popular turn-of-the century playwright. Armstrong wanted a community that included a hotel, an 18-hole golf course, bridle paths, and homes on what was becoming a popular summer vacation center. She commissioned Olmsted Brothers to design a place of leisure, contemplation, and tranquility. John Russell Pope, who designed the Jefferson Memorial, was commissioned to review building designs. Leading golf course designer Charles Banks laid out a nine-hole golf course. Woodlands were maximized, and the beach house, no longer a hotel, was situated to minimize the intrusion of the government towers at Greenbury Point. Curving roads and anomalous lots to match the topography were planned. While the Great Depression put a stop to much of the development, the general design remained. We know it as Annapolis Roads.

Olmsted and his sons pursued a vision of respect for both natural landscape and human amenities. They demonstrated the ethic that a nation and its cities could be parklike in concept, respectful of human scale, and expressive of reverence for life 100 years before Schweitzer and Doxiadis urged us forward. This year, 200 years after Olmsted’s birth, we celebrate the man who left us this legacy. █