+ By Desiree Smith-Daughety + Photos by Dan Hill

Creativity, if stifled, will erupt.

How appropriate, then, that the tool seminal to Dan Hill’s invention of “griddle art” is made of pyroclastic material.

In April 2015, at the end of a long shift as chef on a liftboat (a wide barge that puts down legs upon reaching its destination) in the Gulf of Mexico, Hill created a unique visual arts medium. While performing a task he’s done innumerable times in his 19 years as an executive chef—purging a commercial griddle of the day’s debris—he noticed an interesting pattern as he worked with a little oil and a brick of black pumice stone. The cleaning process had left behind a dark, oily film overlaying the silver sheen of the griddle. Hill next did what countless people who encounter interesting surfaces have done throughout human history: he drew in it. Intrigued by the result, he took a picture of it and then did what many of his contemporaries do: he shared it on Facebook.

In April 2015, at the end of a long shift as chef on a liftboat (a wide barge that puts down legs upon reaching its destination) in the Gulf of Mexico, Hill created a unique visual arts medium. While performing a task he’s done innumerable times in his 19 years as an executive chef—purging a commercial griddle of the day’s debris—he noticed an interesting pattern as he worked with a little oil and a brick of black pumice stone. The cleaning process had left behind a dark, oily film overlaying the silver sheen of the griddle. Hill next did what countless people who encounter interesting surfaces have done throughout human history: he drew in it. Intrigued by the result, he took a picture of it and then did what many of his contemporaries do: he shared it on Facebook.

Little did Hill know this would be the launch of his nascent visual arts career. A couple of hundred people “liked” and commented on that post, asking, “Wow, what is that?”

“It has surprised the hell out of me, because I haven’t so much as doodled since I was about ten.” Hill’s creativity had long been expressed through guitar playing, music writing, and food plating. After working as chef at The Main Ingredient for 12 years he traveled to Baltimore to help a friend open a restaurant, then switched focus back to Annapolis to help other friends open West End Grill. He planned to venture out on his own, but when financial supporvvvtt from potential backers didn’t materialize, fate presented an enticing opportunity. He was hired as a chef on a liftboat servicing smaller offshore oil rigs, feeding up to fifty people three times per day.

Hill always wanted to travel to different places as a chef. He loves his rig gig and how it has opened the world to him. The job provides generous amounts of time to explore. One gig in South America started in Panama and, according to Hill, boosted his Spanish-language capabilities about forty percent. A possible stint in Antarctica at a polar research station is on the horizon. “The oil industry is worldwide. I plan to keep moving around as much as I can—tthe poor man’s Anthony Bourdain!”

Hill always wanted to travel to different places as a chef. He loves his rig gig and how it has opened the world to him. The job provides generous amounts of time to explore. One gig in South America started in Panama and, according to Hill, boosted his Spanish-language capabilities about forty percent. A possible stint in Antarctica at a polar research station is on the horizon. “The oil industry is worldwide. I plan to keep moving around as much as I can—tthe poor man’s Anthony Bourdain!”

This new career path led Hill to his art because, happy as he was, something was missing. Working offshore, the creative part of cooking isn’t present. He doesn’t get to sit down and come up with interesting dishes; it’s mostly down-home comfort food for the workers. And the 15-hour workdays allow little time for playing guitar before dropping off to sleep. Hill’s need for an easily accessible creative release finally found its outlet at the end of a pumice stone.

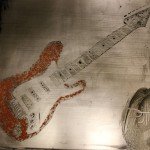

“I started doing one [creation] every day while cleaning. At first, it was abstract, and then moved into something else. What makes it interesting is the medium; it has a unique look to it.” Wanting colors—they had to be food-derived—he started applying spices to the paintings. Hill strives to create one piece daily, but some days nothing is there to inspire him.

The hot griddle creates a liquid surface with the oil and, depending on the oil used, the griddle canvas will be a little grainy and either more liquescent or fairly dry. Hill usually has no preplanned idea, he just steps up and lets it appear. A pattern may present as a horse’s face, for example. “I create a lot of wildlife images,” he says. Hill’s tool kit is an eclectic mix that includes a butter knife, a wooden skewer, his fingers, and a sausage—anything that gives him the texture he’s seeking.

The unique canvas presents Hill with a challenge. Because the paintings are temporary, he documents his work by photographing them with his Canon T2i (he uses a small Fuji waterproof camera when traveling). But after posting his pictures on Facebook, people started requesting prints. Currently, he has about seventy griddle paintings that he has transferred onto canvas. One popular work features a drawing of a plate, knife, fork, spoon, and napkin—with an actual egg that he cooked on top of it. He recently started puzzling over how to make permanent paintings. He met the former manager of a machine shop, who gave him a thin fourteen-by-fourteen piece of steel to experiment with, making a creation on it and then preserving it. To date, all of his business transactions—including selling a griddle art calendar he created—have been through Facebook and more recently an Etsy account.

The unique canvas presents Hill with a challenge. Because the paintings are temporary, he documents his work by photographing them with his Canon T2i (he uses a small Fuji waterproof camera when traveling). But after posting his pictures on Facebook, people started requesting prints. Currently, he has about seventy griddle paintings that he has transferred onto canvas. One popular work features a drawing of a plate, knife, fork, spoon, and napkin—with an actual egg that he cooked on top of it. He recently started puzzling over how to make permanent paintings. He met the former manager of a machine shop, who gave him a thin fourteen-by-fourteen piece of steel to experiment with, making a creation on it and then preserving it. To date, all of his business transactions—including selling a griddle art calendar he created—have been through Facebook and more recently an Etsy account.

New to visual art beyond the plate, Hill describes experiencing “the progression of ideas that leads to better art. The last twenty [pieces] are the best I’ve done out of the lot, I feel.”

Hill’s sense of humor infuses his work. He created one piece that he describes as a “Pollock inside of a Pollock.”

While Hill sometimes finds his art hard to scrape up, he understands one crucial thing about where he is in his process of offering the actual original piece of artwork to sell through his business Graisse Chaudage (“the art of the griddle”): “I can’t buy the griddle.” █