+ By Tom Levine + Color photos by John Bildahl

If a band plays to an empty room, does it make a sound? Larry Freed started the publication Annapolis Music Scene (AMS) in 1989 because he was afraid it wouldn’t make a sound—or at least not for long. He is not a man who likes silence. A drummer and avid music fan, he knew that if there was no audience, there would be no music. When he moved to Annapolis in the early 1980s, he quickly discovered that he was in a town where you could go to a bar on any given night and hear great live music. Thanks to Freed, you still can.

By the late 1980s, Freed started seeing audiences dwindle at local bars and clubs. Being a rational man, he knew that if the crowds kept shrinking, the bar owners would soon lose interest in hiring bands. He didn’t care to watch local live music die a slow death, and became a bit irrational in how he decided to solve this problem.. “[I] quit the day job with a lot of hope and a little bank account,” he recalls, and he started AMS. And as if that wasn’t enough, he dragged a half-dozen friends into the enterprise.

By the late 1980s, Freed started seeing audiences dwindle at local bars and clubs. Being a rational man, he knew that if the crowds kept shrinking, the bar owners would soon lose interest in hiring bands. He didn’t care to watch local live music die a slow death, and became a bit irrational in how he decided to solve this problem.. “[I] quit the day job with a lot of hope and a little bank account,” he recalls, and he started AMS. And as if that wasn’t enough, he dragged a half-dozen friends into the enterprise.

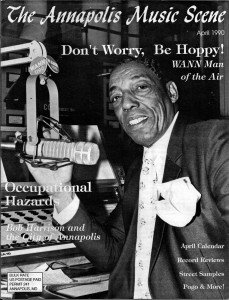

If you received a copy of AMS, it was because Freed had cornered you in a bar and got you to sign on to the mailing list. The first issue came off the presses in February 1989, and was mailed out to 2,000 people. What they got was a newsletter that, as Freed wrote in the first issue, was dedicated to “Keeping the Music Alive” in the Annapolis Area.

One of AMS’ first hires was Greg Allen, who contributed two monthly columns: “Turn it Up” reviewed local bands and “Buried Treasures” shared Allen’s passion for collecting records. He remembers AMS being a bit jagged around the edges. He wrote and submitted his columns in longhand, never before deadline. He left it to others to quickly interpret and transcribe his work. By the time AMS went to print, words were often scrambled, sentences didn’t always make sense, and he couldn’t have cared less. He was writing about rock and roll, and if he and Freed actually had job descriptions, the first line would have read, “Must be willing to go to bars and listen to live music seven nights a week.”

The response after the first issue surprised Freed. “It was as if I poked a little hole in the ground, and all of a sudden, a geyser of oil came flowing out,” he says. Circulation soon grew to 10,000. AMS Command Performances, which featured five local bands for five dollars, were drawing sellout crowds downtown. Freed and company presented singer/songwriter showcases and Have You Heard nights featuring bands from Baltimore and the District of Columbia.

The response after the first issue surprised Freed. “It was as if I poked a little hole in the ground, and all of a sudden, a geyser of oil came flowing out,” he says. Circulation soon grew to 10,000. AMS Command Performances, which featured five local bands for five dollars, were drawing sellout crowds downtown. Freed and company presented singer/songwriter showcases and Have You Heard nights featuring bands from Baltimore and the District of Columbia.

For Freed, this endeavor was all about connectedness. The bands got to know each other and hear each other’s music while the bars started filling up again. Rock and roll was growing in Annapolis, and if Freed didn’t plant the garden, he sure gave its parched soil a big drink of water. Dean Rosenthal, whose fortieth anniversary in the music business was recently celebrated with a sold-out show at Rams Head On Stage, knows how much Freed did for the local music scene. “A lot of people talked about what they were going to do for the music scene, but Larry was the one who actually did it,” he says.

Freed hadn’t really started AMS to support the musicians. He knew that the music scene lived and died with the fans; their connectedness mattered more—to the musicians and to each other. Freed knew that people wanted to be part of a scene, hang out with their friends, feel the beat of live music, and know that they were part of something special, experiencing a unique moment

Art provides an emotional connection to the artist. When you look at a great painting or read a good book, you can feel a part of what the artist felt while creating it. But the finished product is much like a recording—it memorializes a moment, the time when the brush hits canvas or words fly off the keyboard.

Live music brings us face-to-face with its creation, and one of its great pleasures is that you and your friends hear something that never happens in the same way again.

Back in a time before email, before Facebook, and before you could tap your phone to find out who was playing at Armadillo’s or Rams Head Tavern—a time when going viral was never a good thing—AMS gave Annapolis all of that information the old-fashioned way, with paper and ink, staples, handwritten mailing lists, and mail that required a stamp and a trip to the post office.

Freed turned over the reins of AMS by 1991 and wrote his last column in 1993. Allen wrote his last a few years later, and by 2000, with Becky Cooper-Rusteberg as publisher, the magazine became Chesapeake Music Guide (CMG). It had a long run before succumbing to the recession in 2008.

Freed turned over the reins of AMS by 1991 and wrote his last column in 1993. Allen wrote his last a few years later, and by 2000, with Becky Cooper-Rusteberg as publisher, the magazine became Chesapeake Music Guide (CMG). It had a long run before succumbing to the recession in 2008.

So why, over 25 years after Freed started AMS, should this old story matter? Because it still matters. If you aren’t going out to hear live music because you just don’t like music, that’s fine. But if you do like music, even just a little, why wouldn’t you go out for a listen? Annapolis has nurtured a new generation of musicians and fans who play and sing and dance alongside people who were doing this before AMS was born. The scene has evolved, but it’s still the same. It’s joyful and raucous and alive enough that you can lean against a wall in a local club and feel it in your spine and smile while saying thank you to Larry Freed for knowing that it shouldn’t fade away. As Danny and the Juniors told us in the 1950s, and Neil Young reminded us in the 1980s, rock and roll is here to stay. █