+ By Terese Schlachter + Photos courtesy of Ralph Crosby

Attaboy cheers, the smack of wood on rounded resin, and the smell of beer and shoe polish combined to create the atmospheric tincture that drew 15-year-old Ralph Crosby into Pap’s, a onetime pool hall at 183 Main Street in Annapolis.

“I spent untold hours there,” confesses Crosby. By the time he was 18 years old, he would sometimes play at Pap’s prestigious first table, occasionally drawing an audience that included his father. Crosby lived with his family only a block away from the hall. But that’s not where his fascination with board and billiard competition began.

At age six or seven, he managed to contract all the illnesses of the age and era: mumps, scarlet fever, measles, and whooping cough. His mother challenged him to card games to keep him amused and mostly resting through all those hours of recovery. By the time he turned 12, he’d gone hard core, meeting up with his young friends to play baseball, then poker.

“We played for money,” he says, “nickels and dimes. A quarter was a big bet!” All that racking, stacking, holding, and folding taught Crosby the value of practice and created the allure of risk.

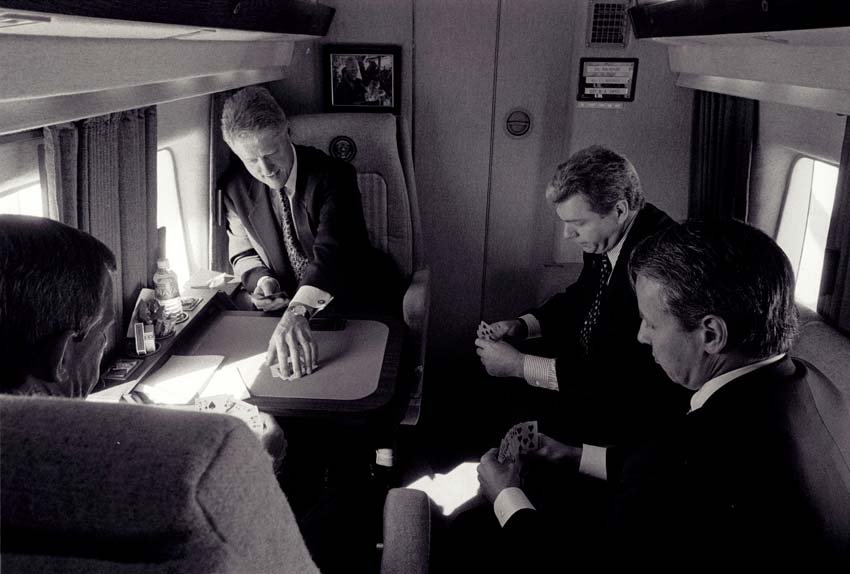

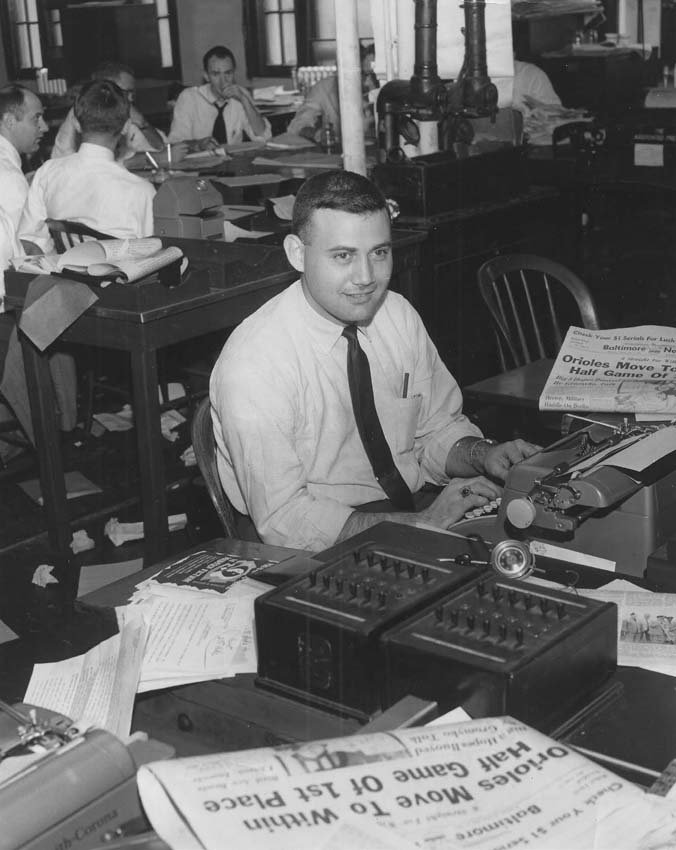

A decade or so later, Crosby became a White House correspondent for the Baltimore News-Post, which provided entrée to a Washington, DC institution: the National Press Club. Founded in 1908, the club was born less from a desire for local journalists to work than to have a drink and play poker. His new colleagues also let him in on some insider information: Theodore Roosevelt and Harry Truman had been poker players, too. What might have been considered by the presidents’ constituents to be a bad habit was kept mostly under wraps. But the peek behind the curtain into the proverbial smoke-filled room long held Crosby’s fascination with strategy and the presidents who did or didn’t master game theory.

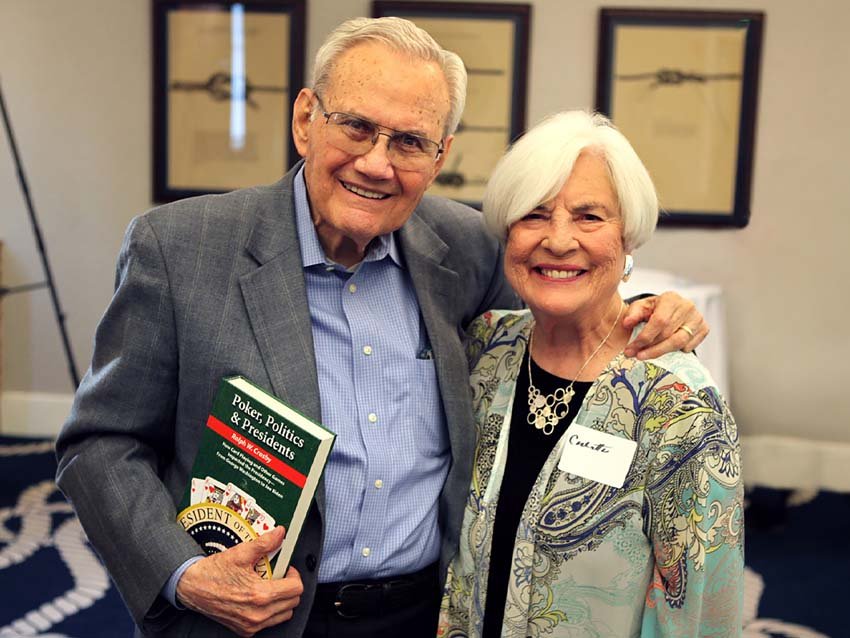

Some 60 years after that press club revelation, Crosby published the product of his early fascination, Poker, Politics and Presidents: How Card Playing and Other Games Impacted the Presidency—From George Washington to Joe Biden (2023, Anaphora Press). The book chronicles the winners, losers, and cheaters who have occupied the White House for the past 234 years, the games those men loved, and the presidential proficiencies they nurtured. “Strategy, risk-taking, bluffing, reading other players—all skills used in poker and politics,” says Crosby. “Diplomacy, too. If you’re good at reading another player, you can tell how [an opponent] might react.”

President Theodore Roosevelt used poker to close the socioeconomic gap between himself and the middle-class men who controlled New York politics. Warren Harding chose his cabinet from among his own poker gang, then lost a set of White House china on a bet. Woodrow Wilson played golf every day, trying to rehabilitate his ailing back. “[Dwight] Eisenhower was the greatest game theorist ever,” says Crosby. Eisenhower was a master poker player who, after once leaving a fellow officer penniless, then rigging the game to be sure the young father won the money back, switched to playing bridge. Later came Operation Overlord, the extremely dicey invasion of France at Normandy during World War II. Failure would have cost thousands more American lives. Success propelled Eisenhower to the presidency, where his own diversionary tactic swung to golf.

One could say that Richard Nixon’s first campaign was based on beating the odds. He financed his 1946 run for Congress with winnings from games he played while in the navy. Crosby writes that Nixon, raised a non-gambling Quaker, thought financial gain was as good a reason as any to forsake his upbringing and put away some cash, and that the thirty-seventh president carried his propensity to take risks all the way through his career, including his pursuit of accused spy Alger Hiss, his famous “Checkers” speech, and his run for the 1968 presidential nomination after already having been beaten by John F. Kennedy and California Governor Pat Brown. Crosby quotes Nixon: “If you take no risks, you will suffer no defeats. But if you take no risks, you win no victories.” He might have added that one miscalculation can cost a career.

The gambling tradition has deep roots. George Washington, despite his mythical tendency to come clean regarding matters of the hatchet, apparently had an intimate relationship with risk. Regular journal entries describe various card games, wins, and losses. His favorite, a precursor to poker, was whist—a game of trickery—known as a thinking-man’s game. The first president of the United States didn’t play cards all the time—he also favored horse racing as well as backgammon, billiards, and cockfights.

Crosby is an ardent follower of George Washington. In his earlier book, Memoirs of a Main Street Boy: Growing Up in America’s Ancient City (2016, Anaphora), he chronicles some of Washington’s visits to Annapolis and traces his own footsteps as he travels in the president’s wake. Crosby is currently pondering his next memoir, which will provide a more complete look at the Founding Fathers’ imprint on Annapolis and Crosby’s similar travels.

Crosby has often applied some of his own early card-turning and fast-break techniques to his career. “Card playing, as with shooting pool, taught me that you have to risk to win,” he says. “Also, then and now, it keeps your mind sharp.”

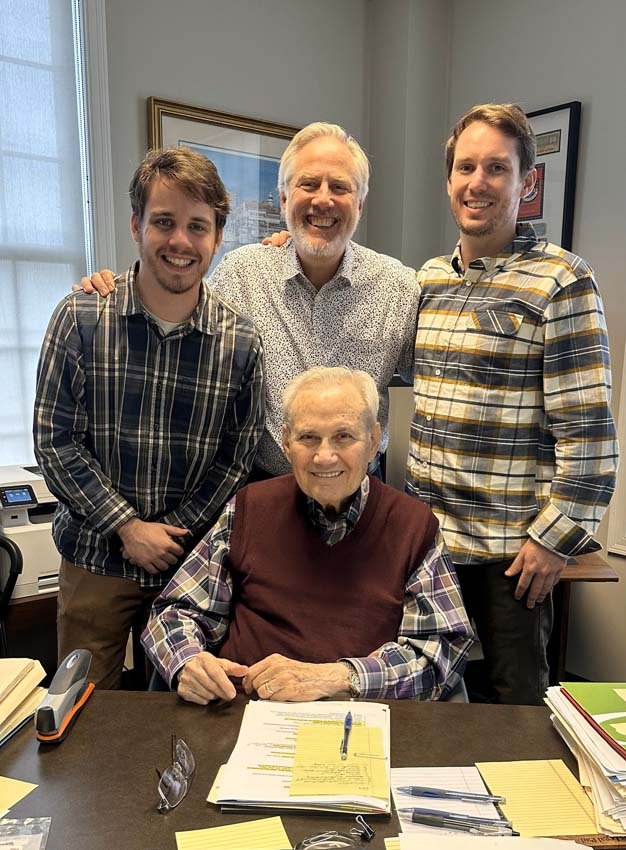

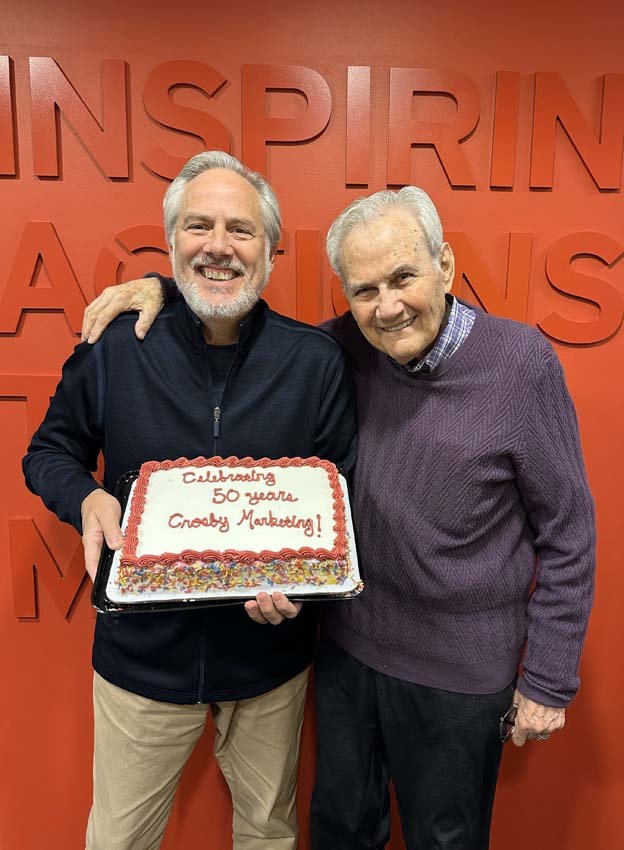

He still goes to his office weekly—he built a successful communications and marketing business, starting with just one employee. Now there are 120. “You have to be able to read a client,” he says. “What could I do to impress them?” Crosby Marketing personnel take pride in their commitment to corporate social responsibility. They count Disabled American Veterans and Catholic Relief Services among their clients.

Known to haunt a local poker game or two, mostly at the Annapolis Yacht Club, these days Crosby is more of a gin rummy player, a card game that depends on the luck of the draw. He celebrated his ninetieth birthday (What are the odds? Only about 30 percent, according to a 2014 Business Insider study.) in December with his family. He loves spending time with his grandchildren, even teaching them the art of the hold versus the fold. “We just use pennies,” he says.

He’s in a position now to study the current workforce—the younger set, those just starting out. His best advice follows that of whom he calls the most “rollicking, game-cocking, horse-racing” US president, Andrew Jackson. “You must risque to win,” Jackson wrote. Despite any current uncertainty, Crosby echoes that sentiment. “If you don’t take a risk, you’ll never know what might have been.”