+ By Julia Gibb

In 1950s Annapolis, a small group of artists gathered in the industrial ambiance of the old Pepsi-Cola plant on West Street. Easels propped up colorful, exuberant art as cigarette smoke hung in the air. Donald Coale, director of the Coale School of Art in Baltimore, walked the gallery and critiqued the works. Among the artists present were Missy Weems, Esther Levy, Virginia Ochs, and Michel Freinek.

Selected works by those four women, whose paths first crossed more than six decades ago, are currently on exhibit in Four Artists: Moving Through Abstraction, at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts. Today’s generation will receive a reminder of a unique time in our City’s art history, when Annapolis nurtured a high-caliber and accomplished avant-garde of abstract expressionist painters.

The exhibit is the brainchild of local artist Thackray Seznec and her daughter, Gwenann Manseau, a lawyer and gatherer of oral histories. Seznec and Manseau, working with artist and curator Sigrid Trumpy, have compiled the works and raised money through their nonprofit, Fox Road Productions, to help fund and organize the show.

After World War II, a fundamental transformation in American painting took place, and the locus of artistic influence shifted from Europe to the United States, primarily New York City. Abstract expressionism emerged as the most influential of new artistic tendencies brought about by the war’s upheaval, as artists searched for a way to navigate a culture shaken by the unimaginable atrocities of war and genocide. Along with well-known male abstract expressionists, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Mark Rothko, were the talented and equally groundbreaking artists Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, and Grace Hartigan.

Hartigan later moved to Baltimore, where she was embraced by that art community, taught at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), and stayed involved for four decades. She also served as a link between the core group of artists and intellectuals who met at the legendary Cedar Bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village to drink, argue, and plot their next moves, a firsthand messenger from the big-city front lines. Hartigan also served as inspiration and teacher to the four artists featured in the exhibit.

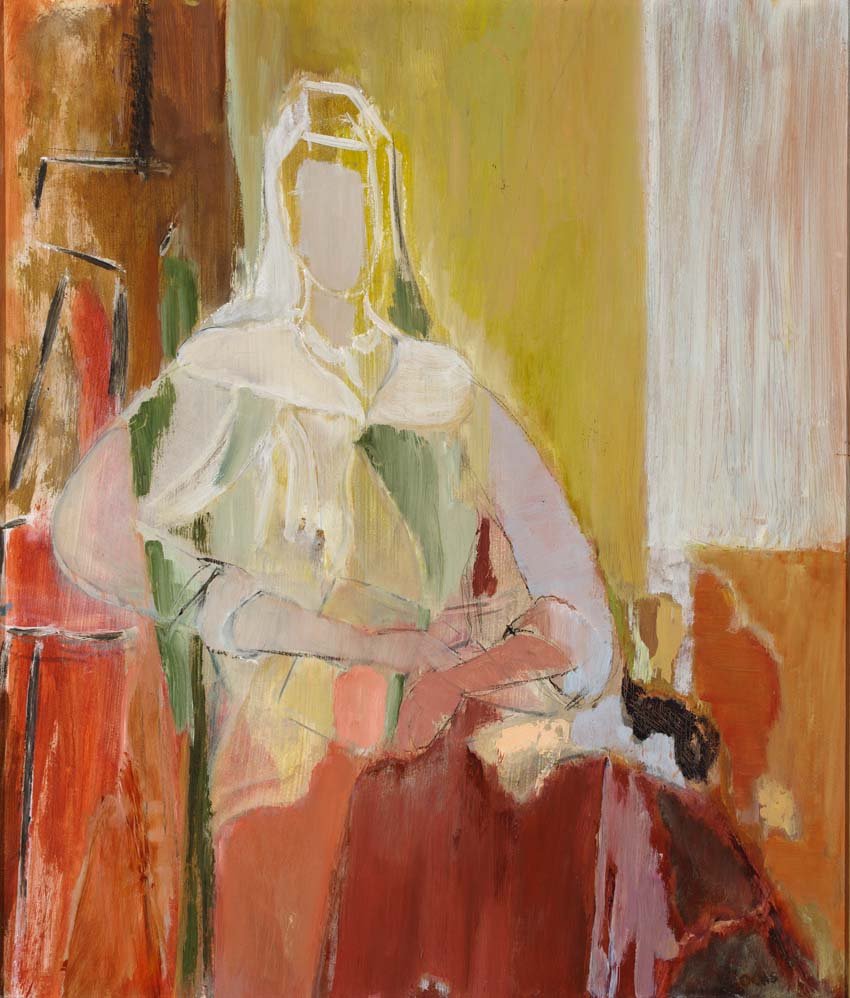

Missy Weems was an Annapolis native, the daughter of revered master air and celestial navigator Philip Van Horn Weems. The Navy career of her husband, Charles R. Dodds, created a life of frequent travel for the artist, and she dedicated herself to studying and practicing art wherever his assignments took them.

Once she and her husband settled on a farm just outside of Annapolis, Weems dedicated her energy to the local arts community. Weems studied at MICA, and her artistic accomplishments included exhibitions at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Baltimore Museum of Art, among other respected institutions. She helped establish the Maryland Federation of the Arts, which has for decades exhibited thousands of local and national artists.

When people asked her how, as a wife and mother, she managed to spend so much time in the studio, Seznec remembers her mother saying crisply, “I make the time.” Weems would work late at night and into the morning hours, rising late to start her day. She made time for occasional late-night bohemian parties, rowdy with music and singing. Seznec, who remembers feeling serious about art by the age of eight, sometimes attended the critiques.

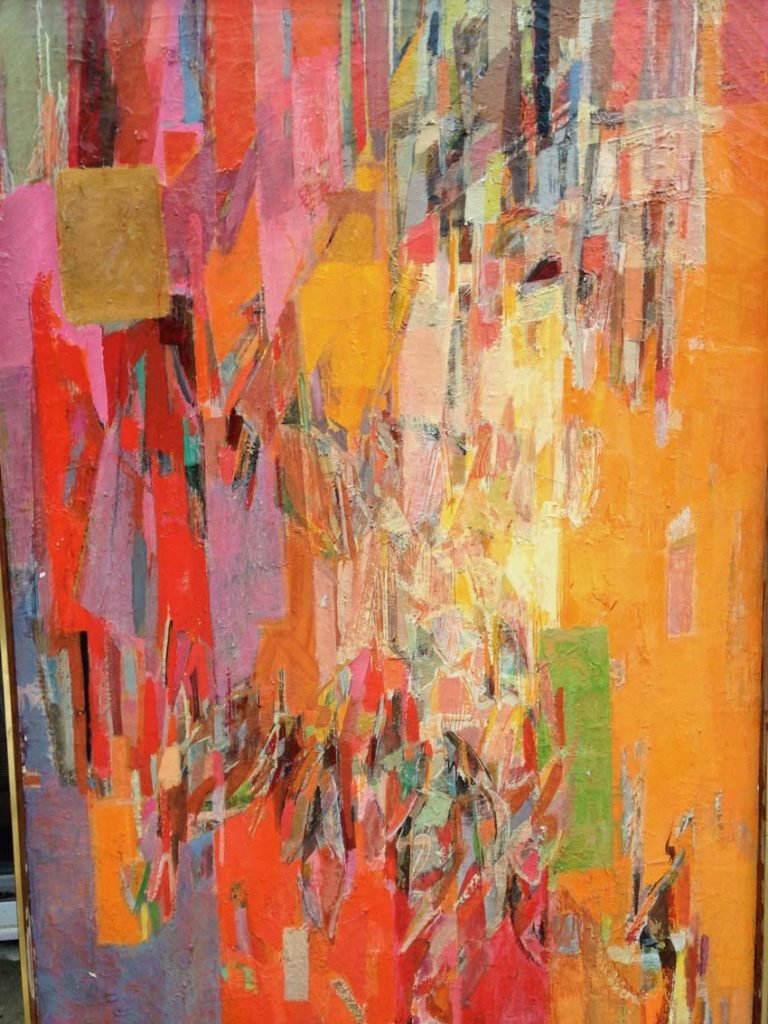

Weems’ work is distinguished by hard edges and pronounced diagonals dissecting the work into rectangular or triangular quadrants of color. In Nocturne (Eastport from Market Quay), Weems employs a horizontal composition, repeating long rectilinear shapes in dusky blues and greens. A strong diagonal suggests a boat sail and disrupts the rhythm of the horizontal elements. In Color Study, she takes a turn toward vibrant colors, the exuberance of which is echoed throughout the vertical composition. Areas of fractured color suggest movement, evoking the iconic Marcel Duchamp painting Nude Descending a Staircase (circa 1912). The motion draws the viewer to a bright gold area of the canvas that lends a sense of opening to an unspecified, mysterious scene.

Combining saturated colors and gestural lines, Interior I suggests a room in refracted shapes and hues. Some elements are rendered representationally—one gets a glimpse of some clearly rendered lathe-turned furniture legs. The feeling is of a transparent layering of time, a residue of perception and memory.

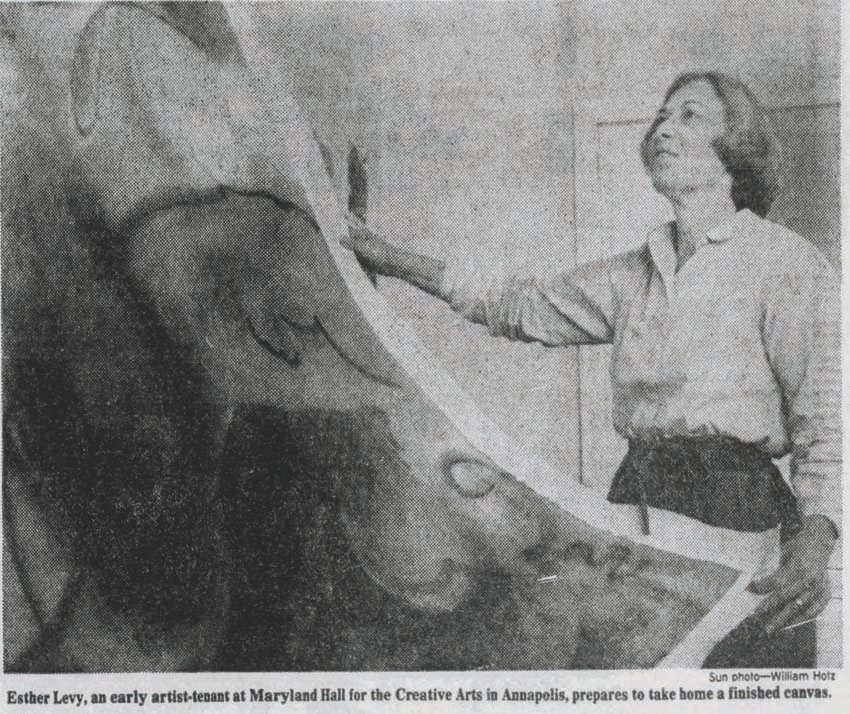

Born in Ohio, to Russian immigrants, Esther Levy moved with her family to Baltimore when she was 13 years old. Widowed at age 26, she immersed herself in the study of art, marrying it with a passion for music. Levy moved with her second husband, Buddy Levy, to his hometown of Annapolis, where, in 1952, they opened Capital Drugs, a pharmacy and gathering place for the community on West Street. They both loved jazz and frequently played it on the phonograph in the pharmacy. Now occupied by Light House Bistro, the pharmacy building is fittingly located in the Annapolis Arts District. On its external wall, facing Monroe Street, a mural by Sally Comport pays homage to the building’s history and the Levy family.

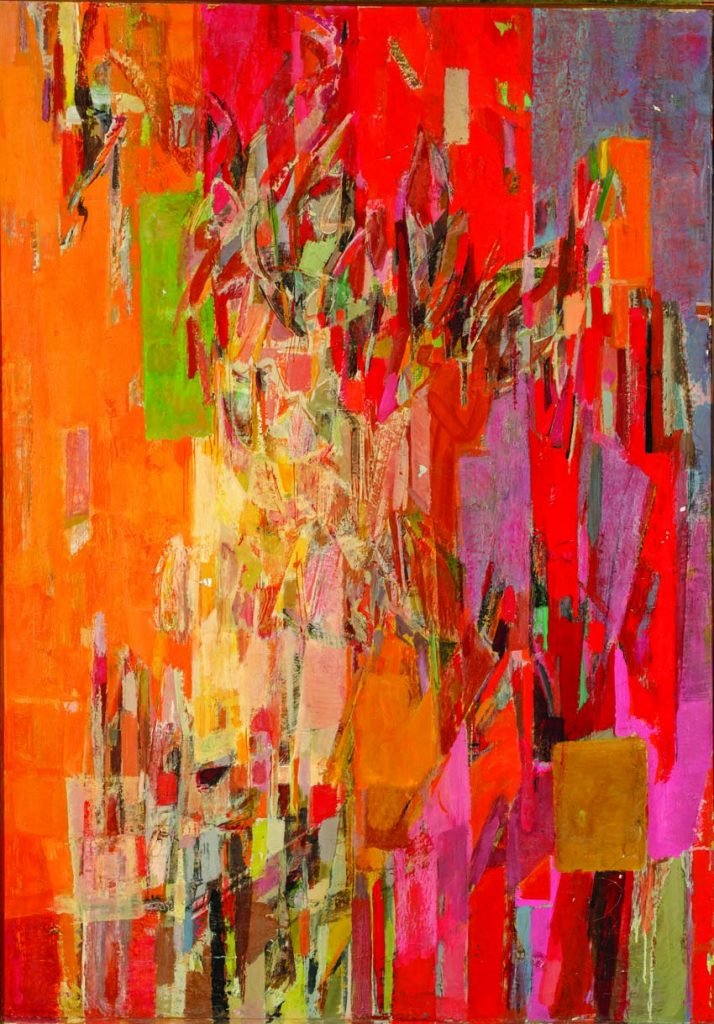

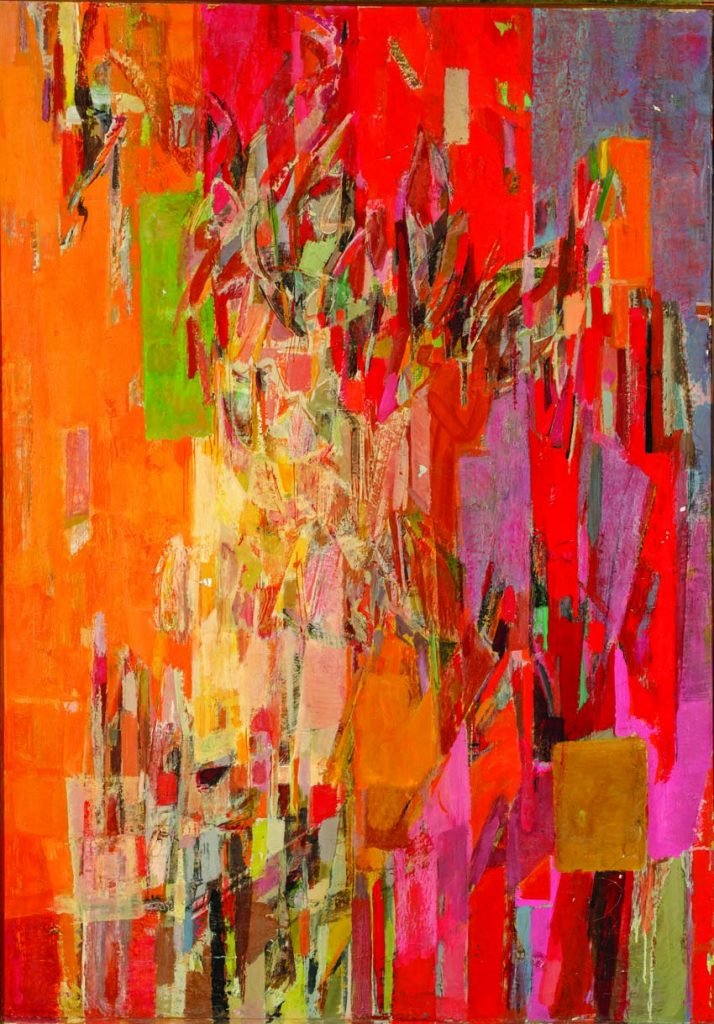

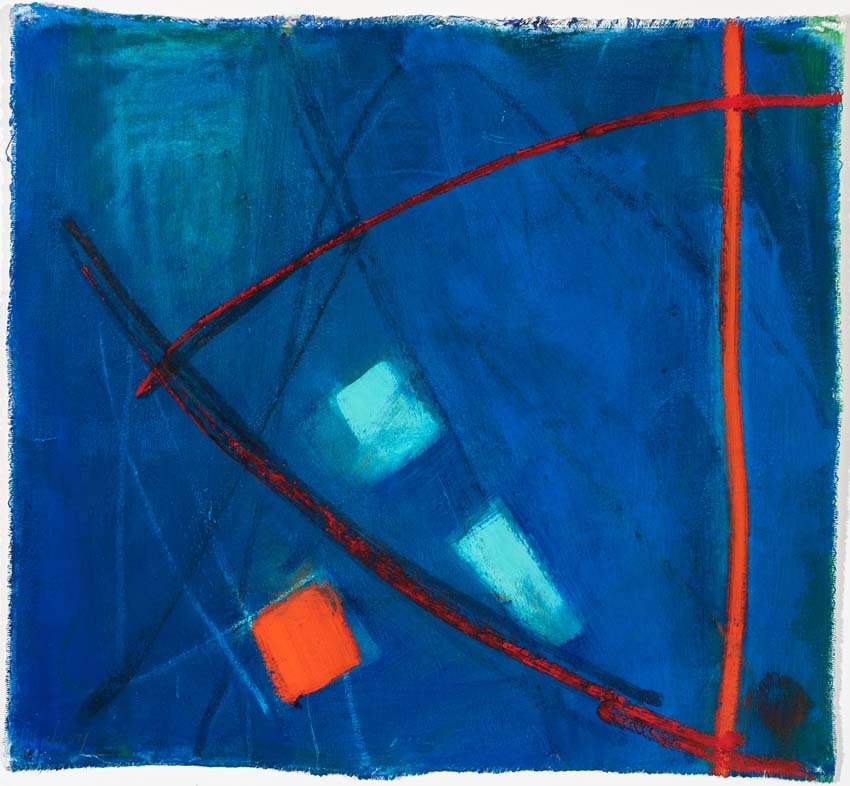

Levy often worked at large scale, on canvases sometimes taller than herself. Her love of jazz carried into her artwork, as she would listen to the music as she worked, letting the sounds influence her art, sometimes appropriating song titles to name her paintings. In Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, Levy creates a smoky, hot ambiance, rendered in warm reds, purples, and an accent of blue, colors transitioning smoothly from one to another. The composition is punctuated by sharp gestural linear markings. On the left, some lines suggest rhythm, while in the upper right, others trail off into a meandering solo. In Untitled (Orange), there is a sense of spaciousness. A few hard edges dissolving into softly blended areas suggest mountains receding into the distance. Two lines in contrasting blue and green anchor the composition with a stabilizing triangular element, and a horizontal ellipse suggests water in a pond. A single blue square in the upper left quadrant draws the viewer’s eye. Her compositional arrangements are both expressive and deliberate.

New York City native Virginia Ochs came to Annapolis via her marriage to Dr. Irving Ochs, whose practice was on Southgate Avenue. She began studying art seriously later in life, when her son Max was a teenager. Though her husband was hesitant and perhaps somewhat intimidated by the world of abstract art, he was also an artist—a photographer—and would support his wife at events.

Max Ochs recalls his mother feeling a sense of complete power and agency when she was creating. “Knowing what it’s like to be free—that’s what art represented to her,” he says. She asserted her right to study seriously and set aside time to paint in her attic studio, studying under Baltimore artists James Gilbert, Grace Hartigan, and Donald Coale. Her son recalls Coale’s persistent focus on the positive in the artists’ work during Pepsi-Cola factory critiques. “He would keep emphasizing what they got right, so that soon, since [the canvas] is a limited space, there wouldn’t be room for anything wrong.”

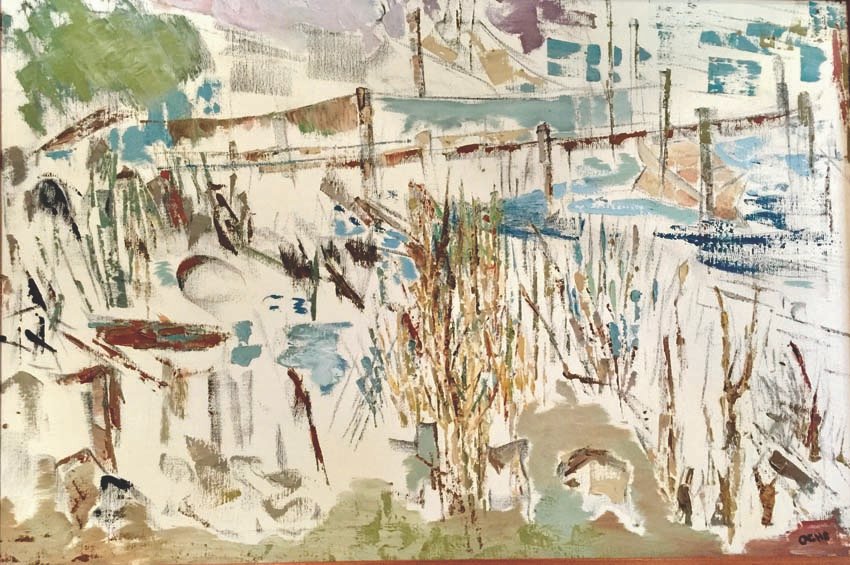

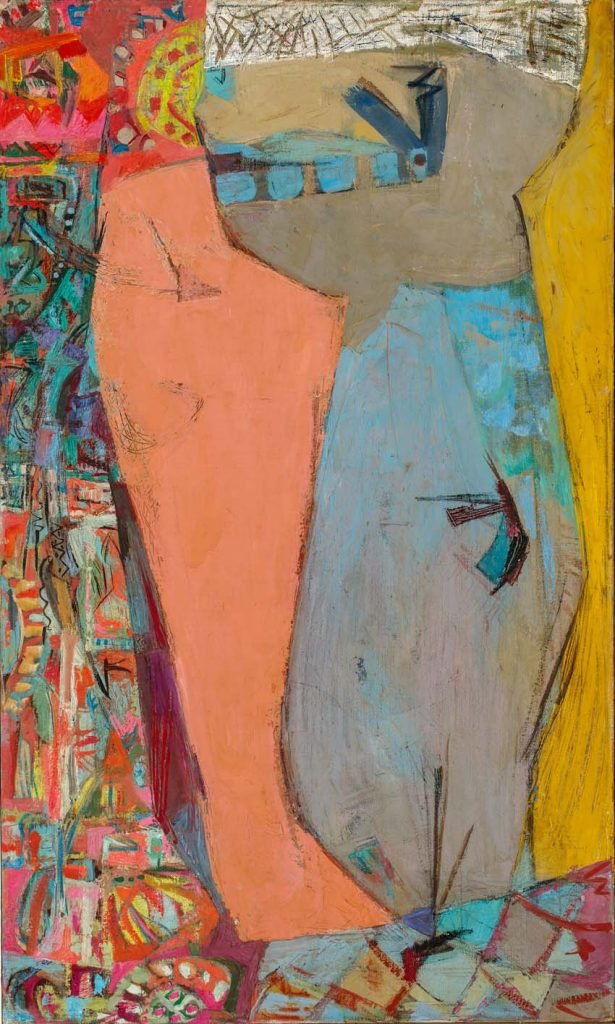

Ochs has the most subtle palette of the four artists, often working in pastel tones, grays, and blacks. In her oil paintings, she shows a sparing touch, seemingly letting areas of canvas remain unpainted. In Bridge at Eastport, brush marks are left raw and sparse, roughing out the shape of a bridge in this panoramically formatted painting. Eventually she began experimenting with cut or torn pieces of canvas, collaged onto other canvases and painted in grays and blacks. Many of these compositions have consistently leveled rectangles placed in graphically pleasing proportions, painted with colors that differ subtly from each other. In Imperfection, however, a large white rectangle sits askew from the rest of the composition, creating a sense of tension not found in some of her other collage pieces. Other compositions introduce curiously precise circular shapes. In Chanticleer, the fabled rooster is depicted by a series of circles and circle fragments. The body is perfectly round, the tail an upsweep of pointed crescents. Composition 92, horizontal with a single, carefully constructed circle, confined into and visually superimposed within surrounding rectilinear pieces, exudes a sense of curiosity. Its rough-edged rectangles lend a sculptural feel, the paint thick and tar-like. The arrangement creates a space in which to wander, reminiscent of Louise Nevelson’s iconic monochrome wall-mounted sculptures, and seems to represent a journey from tentative to bold.

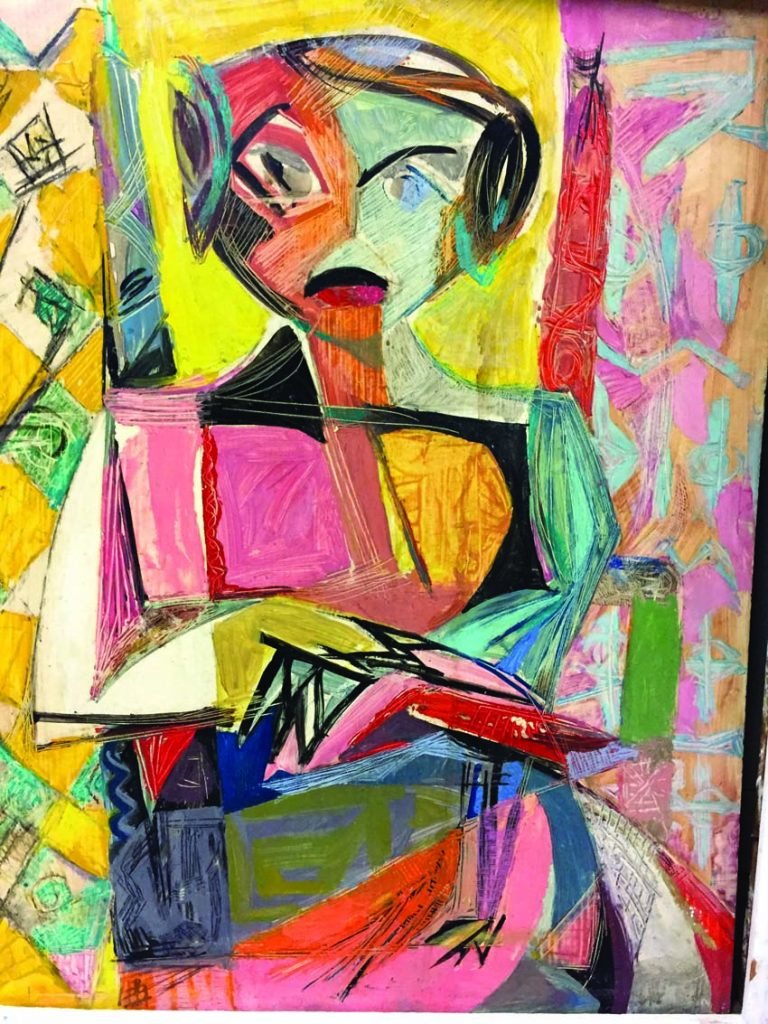

Gertrude St. Michel Freinek, also known as Michel Freinek, signed her paintings “M i c h e l.” Born in Trier, Germany, she spent her teen years in New York City, but after the death of her father, returned home. She studied color theory and color chemistry at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, Austria. Her marriage to Dr. Wilfried R. Freinek took her back to New York and then to Annapolis, where she became part of the community of artists exploring abstract expressionism. Seznec remembers her as a husky-voiced, worldly woman. When Seznec was preparing to go abroad to study and paint, Freinek generously shared some of her experiences traveling and creating art, giving her specific instructions and tips on what to bring and how to remember the essence of a place. “She told me,” says Seznec, “‘wherever you go, bring back a stone, or sand, or a leaf pressed in a book, and you will immediately remember the place—vividly!’ It’s true!”

Freinek experimented with different media, including prints on paper, watercolor, scratchboard, and oils. Her work appears to have a strong foundation in line drawing. Some works reveal a visible infrastructure within a layered painting, composed of varied intersecting lines forming a gridwork of geometric shapes. Others use the practice of contour drawing, or continuous line drawing, as evidenced in Ancestors, a 1967 print on paper depicting a mass of faces that dominate the composition, linked together by a singular line. In Untitled (Church) a 1960 watercolor, strong, angular, and thin but deliberate outlines suggest the shape of a church. Heavy, muted swaths of color rendered with various degrees of control, lend this work an overall gestural painterliness. In The Terrace, a medium-scale oil on canvas with a light, airy palette, triangles and trapezoids form trees, houses, rooftops, and terrace tiles. Providing a bird’s-eye view of a village. A cat, curled in the lower left corner, provides a sense of scale and life to the scenery. In Untitled (Spa Creek Bridge), Freinek employs an aquatic palette of blues and greens, accentuated with fragments of white, suggesting iconic elements of Annapolis, with triangular shapes appearing to signify boat sails and church steeples. Having lived and studied in major art cities from New York to Vienna, Freinek delivered a high-caliber punch of art world experience to Annapolis.

Fox Road Productions’ founders, board members, and advisory board assembled earlier this year to collect and view the four artists’ artwork and share stories and remembrances about their careers and lives. Aware that it is impossible to reconstruct the nature of the friendships or working relationships between the women, the group is doing its best to honor their memories. In curating the exhibit, says Seznec, they were careful to choose paintings that have “conversations” between each other. Seznec laughs, “They’re going to be just so noisy at night when they close the gallery, just chatting with each other.” █

Four Artists: Moving Through Abstraction is at the Chaney Gallery at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts from September 3 through October 26, 2019.

For more information, visit

www.marylandhall.org.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Missy Weems, Woman with Chicken, oil on masonite, 15 3/4 in. x 20 in. Collection of Thackray Seznec.

Esther Levy. Photo credit: William Hotz.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Virginia Ochs, Spa Creek, 1961, oil on canvas, 36 in. x 24 in. Collection of Charles Feldman.

Virginia Ochs in an undated photo. Courtesy of the artist’s son.

Gertrude St. Michel Freinek in an undated photo. Courtesy of the artist’s son.

Esther Levy, Untitled, oil on canvas, 42 in. x 60 in. Collection of Joyce Gomoljak.

Gertrude St. Michel Freinek, The Bridge (Annapolis), oil on canvas, 47 in. x 49 in. Collection of Chris Michel.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Missy Weems and Virginia Ochs at an art gallery. Caption to be confirmed. Evening Capital.

Missy Weems, Color Study, c. 1960, oil on masonite, 34 in. x 48 in. Collection of Thackray Seznec.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Missy Weems painting at her home on Franklin Street, Annapolis. Photo credit: Evening Capital.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Gertrude St. Michel Freinek, The Terrace, oil on canvas, 45 in. x 35 in. Collection of the McWethy Family.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Esther Levy, Untitled, oil on canvas, 42 in. x 60 in. Collection of Joyce Gomoljak.

Virginia Ochs, Imperfection, collaged canvas, 50 in. x 35 in. Collection of Maxwell Ochs.

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos

Photo by Dimitri Fotos