+ By Julia Gibb

Ussy-sur-Marne is an ancient farming town on the Marne River, a 45-minute train ride east from Paris, France. With a nine-centuries-old church at its heart and stone walls dating back to the time of Christ, Ussy puts Annapolis’ idea of a historic town into perspective.

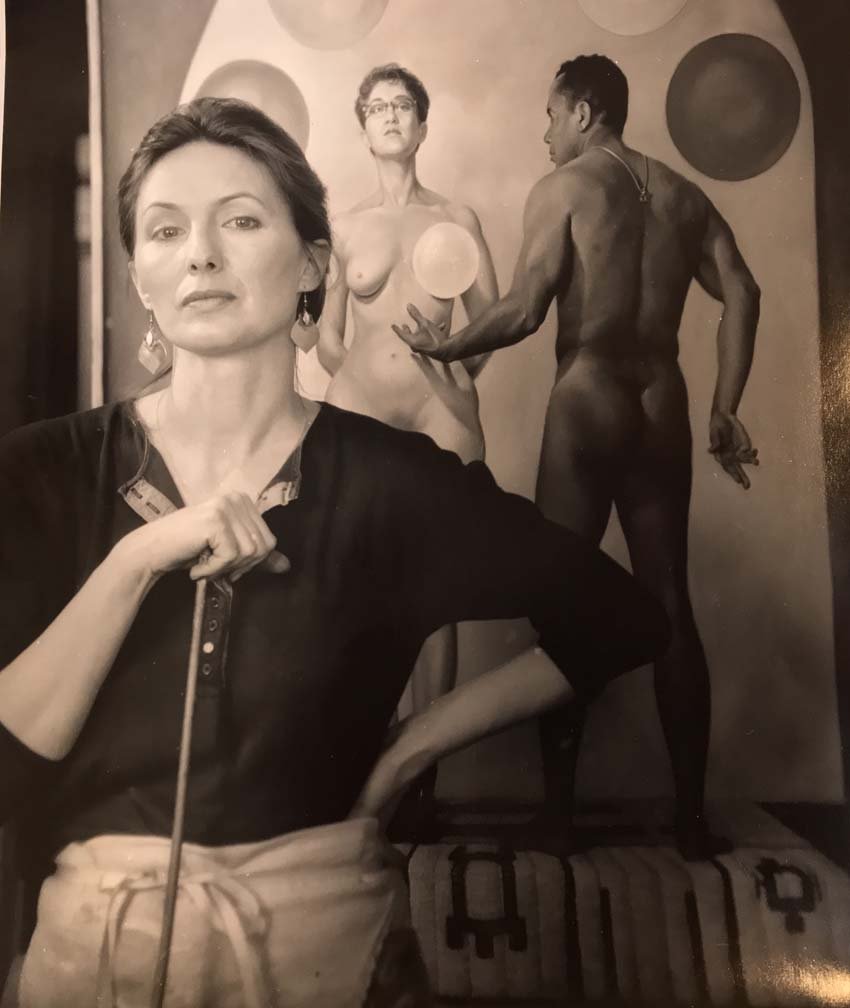

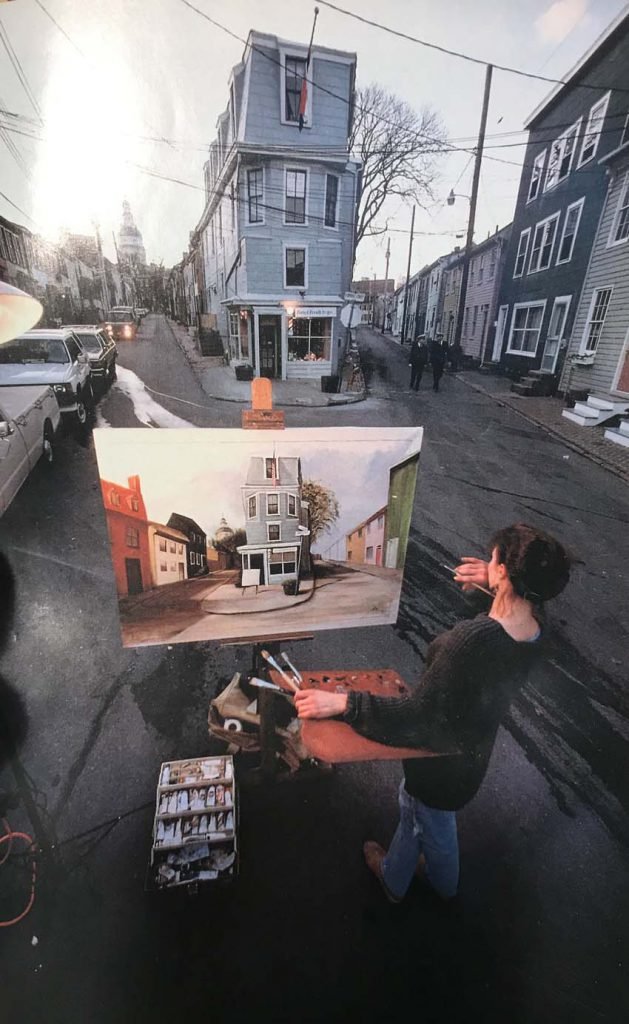

Moe Hanson Delaitre, portrait and figure painter, and over the last few years, street artist inspired by the graffiti of Paris, is an American expatriate. She grew up in Upstate New York, where her interest in art began early. With other artists in the family, she never questioned her own path as an artist. In the early 1980s, she moved to the Annapolis area, where she became a key member of the artistic community. While still living in Annapolis, Delaitre met her future husband, Jean-François, at a wedding in Southern France. “It was love at first sight, and it changed both of our lives, radically, on the spot.” After seven years of traveling between the States and France with older daughter Bessie Turner, son Jack Turner, and now-teenage daughter Ella, the family moved to France permanently in 2009. Delaitre maintains close connections in the States with friends, family, and Annapolis’ art community, returning at least twice a year to visit. Bessie and Jack now both live in Annapolis.

Delaitre lives on an operating farm on property that has been in her husband’s family for generations. This is a place where a vegetable garden is a given, providing rows of tomatoes, greens, and winter squash, as well as flowers grown just for beauty. Stroll out the back of the property, and one can walk for miles along rolling, bucolic farmland, hedgerows, tree breaks, and streams. The attitude about wandering on the property of others is more relaxed there than in the States, and it feels as if one might walk forever. The open skies can shift from sunny to cloudy to bruise-colored and stormy fairly quickly. As one walks back toward the Delaitre property, the view is dominated by three large silo-type buildings, dark green, with sloping, gently pointed roofs. Inside the Delaitre home, one finds the classic beauty of a rustic, 500-year-old farmhouse, with exposed timbers and eccentric winding staircases, and filled with homey touches, contemporary art, and tall rubber boots.

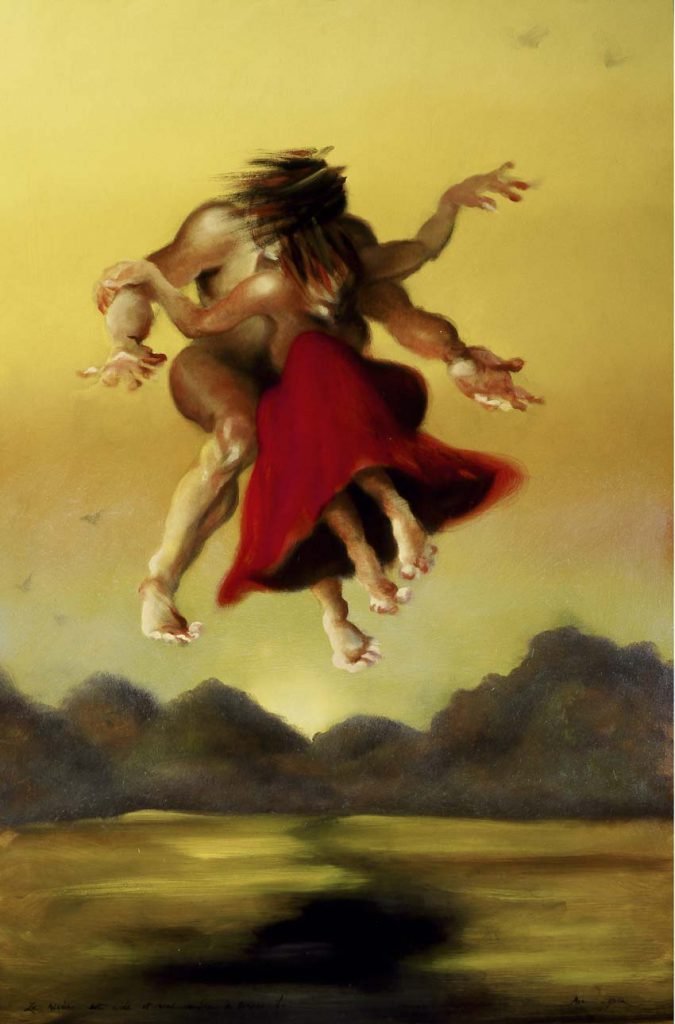

After moving to Annapolis, Delaitre began to study under Baltimore artist David Zuccarini. He belonged to a lineage of painters known as the Baltimore Realists and taught the principles of Maroger—an Old Masters technique whereby a medium is used to build thin, translucent skins of oil paint to render a lush, lifelike quality, the recipe of which was developed by artist and conservator Jacques Maroger. After ten years, Zuccarini pushed his apprentice out of the nest. “He told me it was time to do or die,” she says. Although Delaitre hasn’t spoken to her former teacher in years, she says, “I do think of him every day, I do still hear his words in my head when I try to bend a shadow.”

While studying with Zuccarini, Delaitre maintained a studio residency at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts in Annapolis, where she worked until 2002. “It was heaven at Maryland Hall, back in those days,” she says, recalling the sense of community. “Every studio was full.” She describes how the artists would pool their resources, throwing dance parties to raise money when the facility needed electrical upgrades or other improvements.

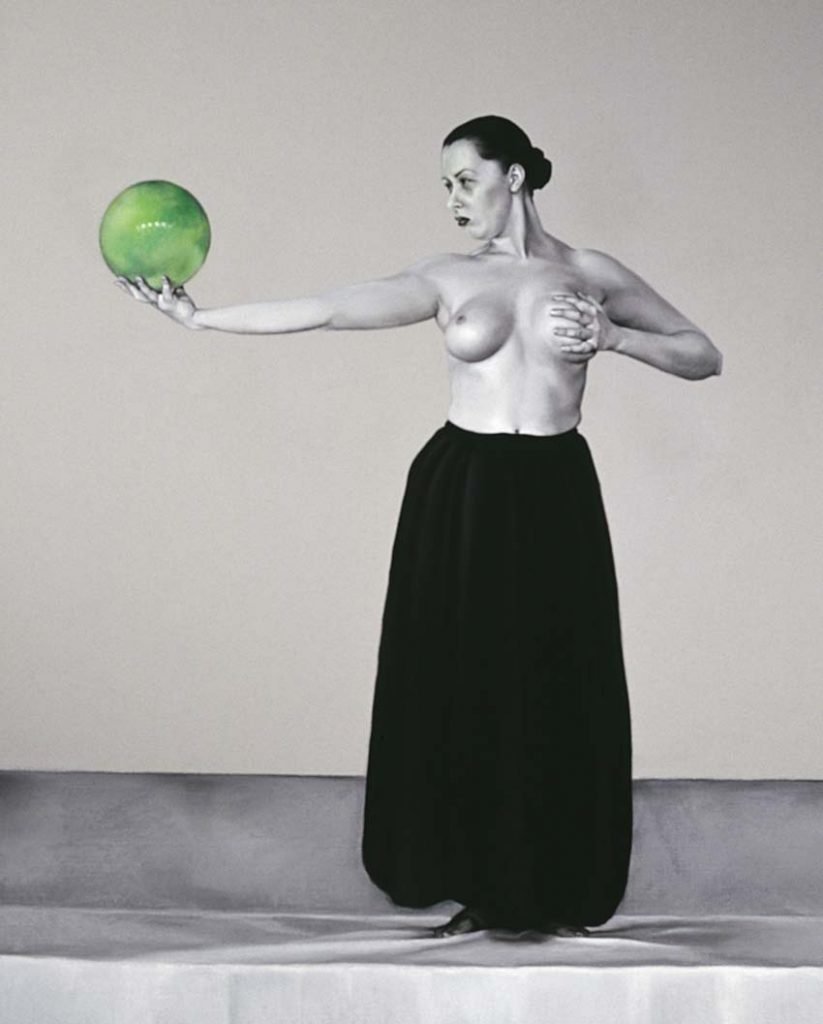

Delaitre’s early work contains nods to her formal background in the use of form, color, composition, and symbolic imagery. Pastel compositions are rendered in incredibly tight detail, with richness, darkness, and saturated color rarely seen with the medium. Her older, commissioned portraits often reveal a twist that gives them a contemporary edge, such as an unexpected figure peering around a corner from down a long dark hallway, adding mystery to the work’s narrative, as the main subject dominates the foreground, posing with her house pets and flanked by pictures of horses hung on the walls.

“Her subjects were always specifically posed, placed in a specific setting, with small details that only hold significance with the individual or family in the painting [for example, a family’s beloved horses appearing on the wall in the background of Kristen Pratt at Wolf Run, 2003]” says Delaitre’s son, who is an accomplished photographer. “I think this attention to detail has influenced my photography, and I always look for small details that go unnoticed by the majority of viewers—details that hold a special significance if you know where to look.”

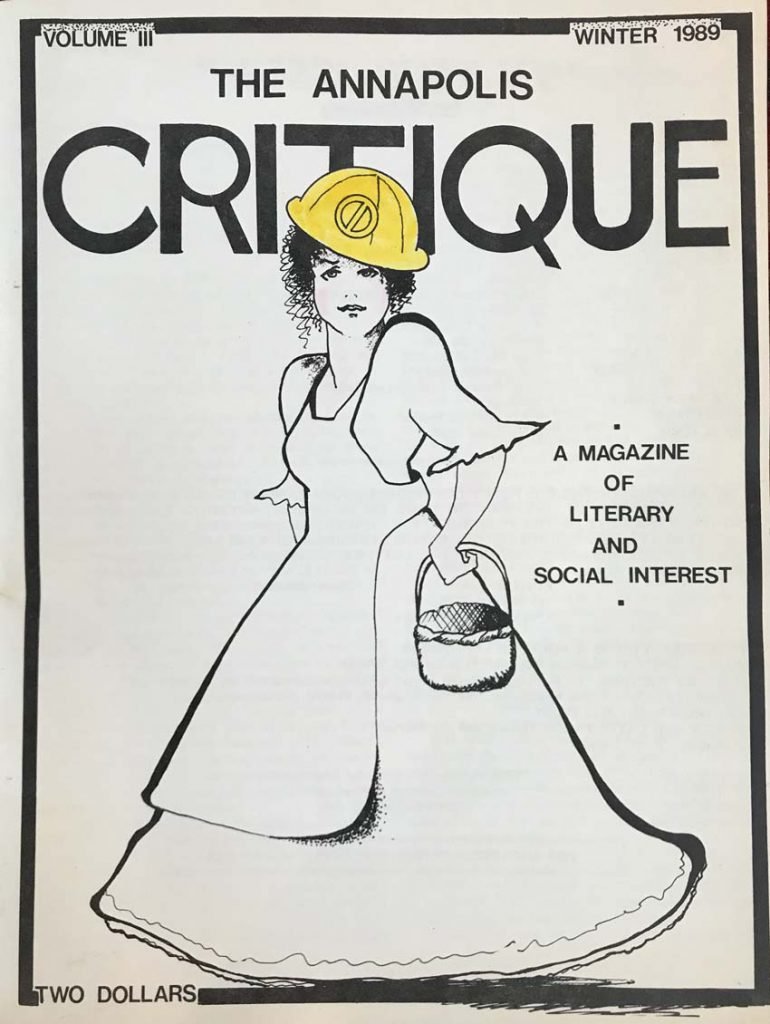

While in Annapolis, Delaitre built a vast clientele, becoming a sought-after portraitist. She formed relationships with local artists, galleries, and small businesses, and is still represented locally by Katherine Burke’s Annapolis Collection Gallery. Her works are in numerous permanent public and private collections, including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, the US Naval Academy, and the University of Maryland’s Dental Museum. They have also appeared on magazine and book covers such as National Geographic and for Miramax-Hyperion publishing. In 2007, she was invited to exhibit in the Florence Biennale in Italy. The American University of Paris gave her her first solo exhibit in France in 2014, and she is represented in Paris by Galerie Martine Moisan. In December 2018, she had a dual-gallery opening at the Annapolis Collection Gallery and ArtFarm, a local multimedia art space, on the same night, just a couple of storefronts apart; her edgier work was displayed at ArtFarm while her more conventional portraits were shown at the Annapolis Collection Gallery.

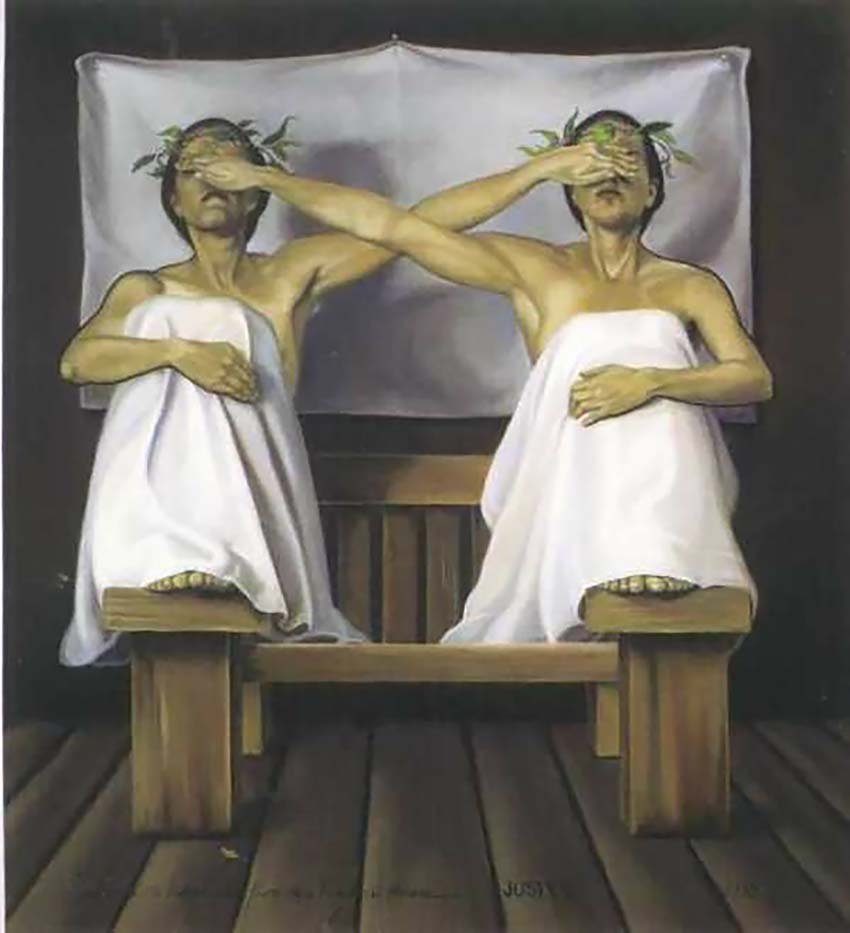

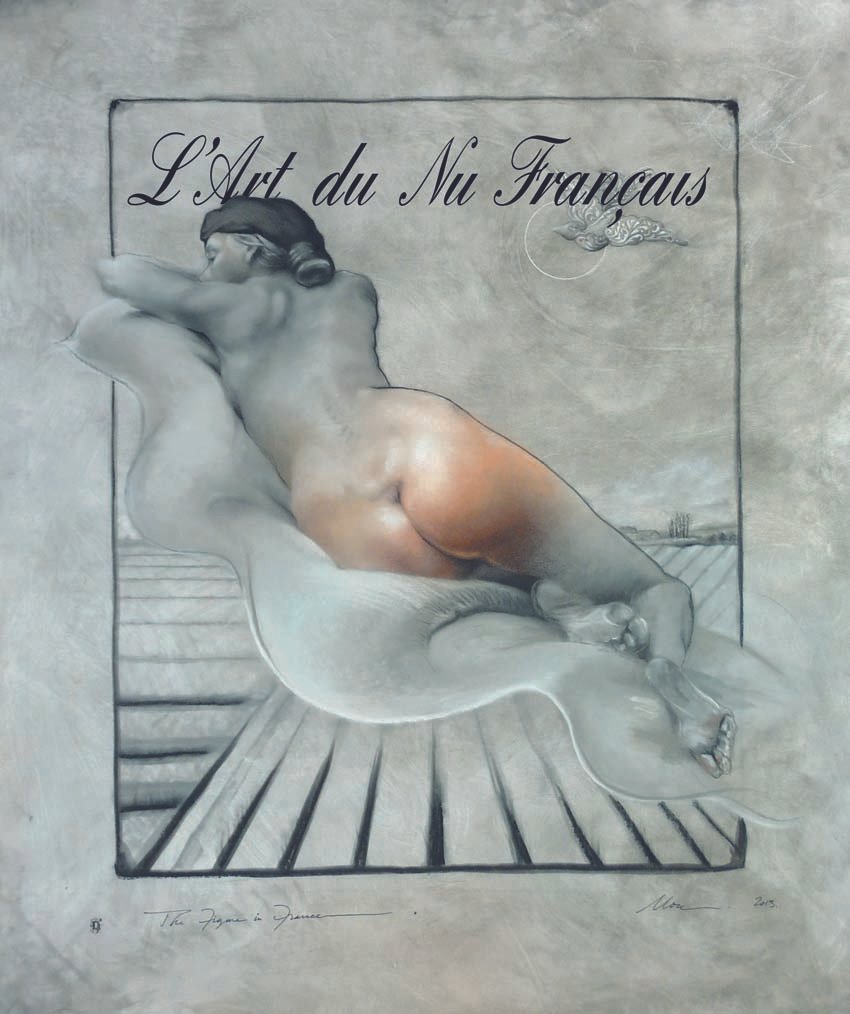

In 2013, another body of Delaitre’s work made its way from Ussy-sur-Marne to Annapolis. L’Art du Nu Francais (The Art of the French Nude) consisted of 33 figure paintings of women from her French village and was exhibited at 49 West Coffeehouse, Winebar & Gallery. Delaitre had met the women around town, at her daughter’s school, and spoke with them about posing for her in her studio, located adjacent to the family home on the farm. She had all of the women assume the same pose, reclining on their side, looking away from the viewer. The figure forms a diagonal within the composition, with an emphasis drawn to the swell of their buttocks, the roundness treated with special care of color and highlights. She asked the women to imagine floating over the rolling fields surrounding their village. In talking and working with these women, she felt herself becoming more integrated with the community she now calls home.

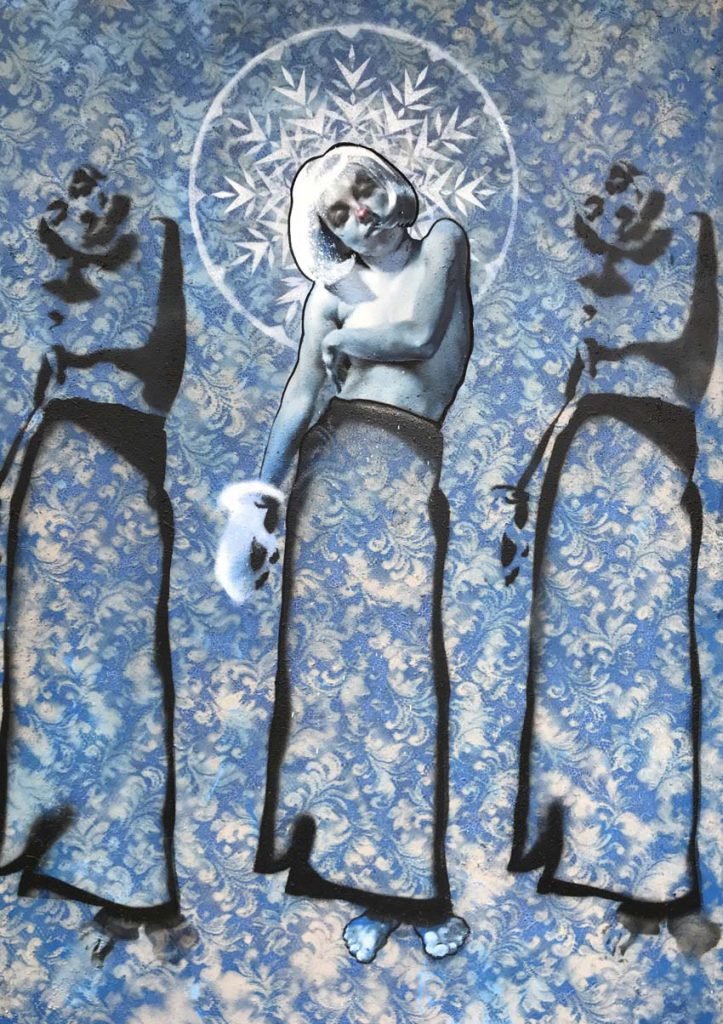

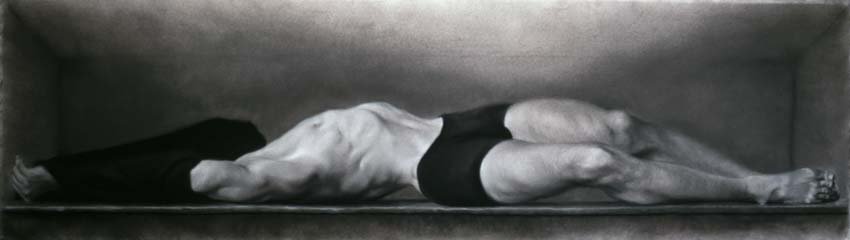

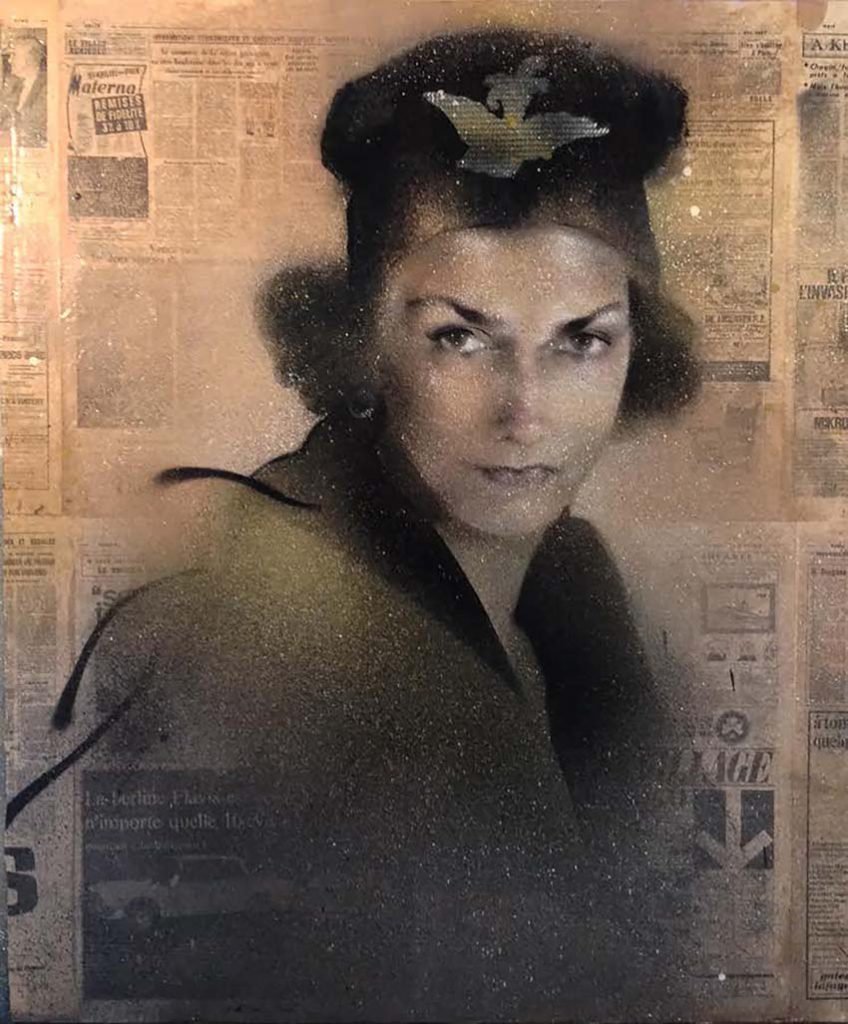

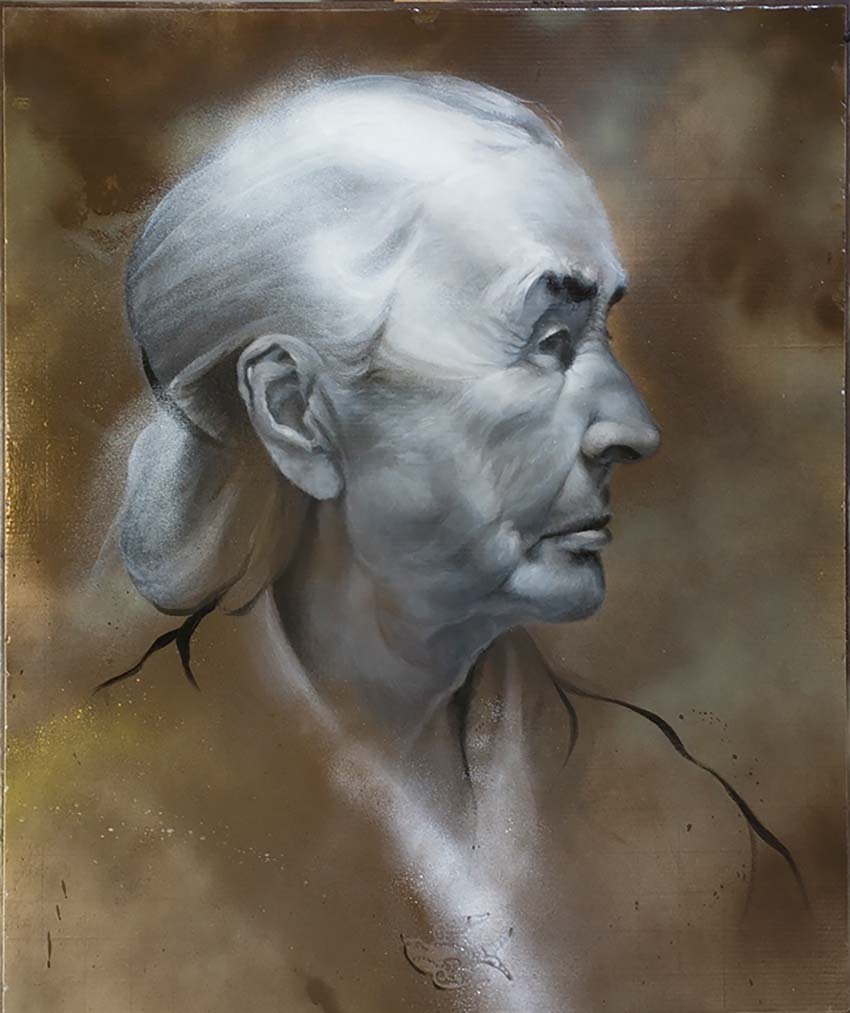

Delaitre’s most recent portraits are only “traditional” at first glance. Since embracing an obsession with street art, she began incorporating more contemporary methods and materials into her repertoire, including spray paint, seed cartons, farming equipment containers, and meticulously cut stencils. “They make strangely comfortable partners with the traditional portrait,” she expresses in a blog post. “The dirty, often oil-stained cartons have gotten me to loosen my realist grip and free up my inner art student.”

The results of her spray-painted portraits on cardboard are astonishing, managing to appear at first as hyperrealistic charcoal drawings or traditional grisaille oil paintings. Only on closer inspection can the viewer realize the imperfect spatter of aerosol and the dented corrugated surface of the cartons. “It’s understandable to see hyperrealistic aerosol portraits on a monumental street art scale, but to see them executed on a smaller scale—it took me a while to wrap my mind around what turns out to be a very obsessive process. Just to create one eye or lip, she has to create so many different stencils,” says fellow portrait artist Jeff Huntington. “She’s using new materials to speak an old language.”

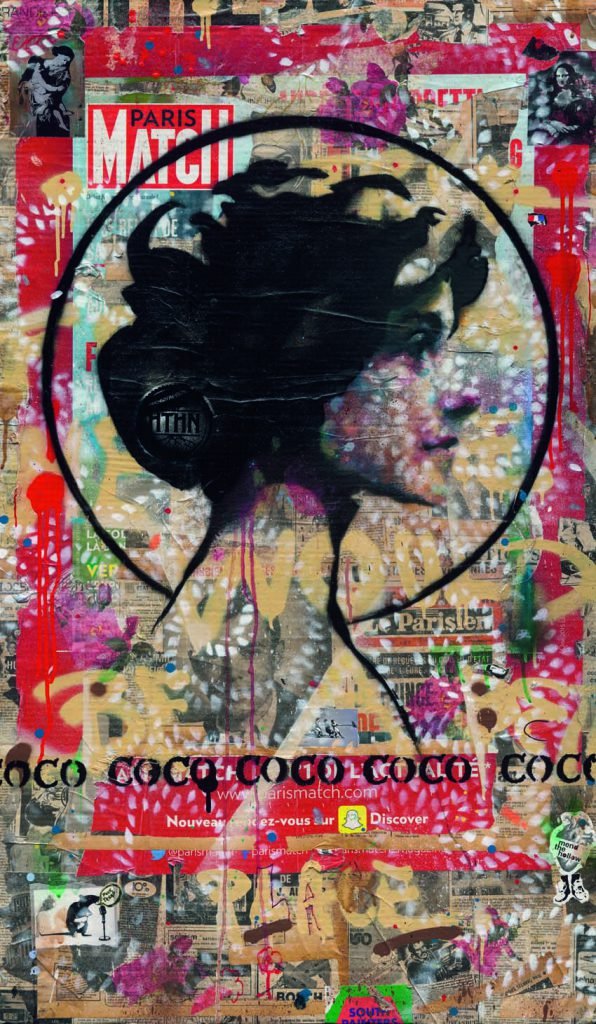

A series of stencil art depicting a young Coco Chanel in profile has become a well-known motif in Delaitre’s work, and it opened her up to the world of street art. As a novice in this particular genre, she has received a warm welcome and generous help from other urban artists. Although Parisian culture is more accepting of graffiti and street art than is her former home of Annapolis, she still gets a rush from creating pieces within seconds in the urban landscape of Paris, in the dark of night, in danger of being caught.

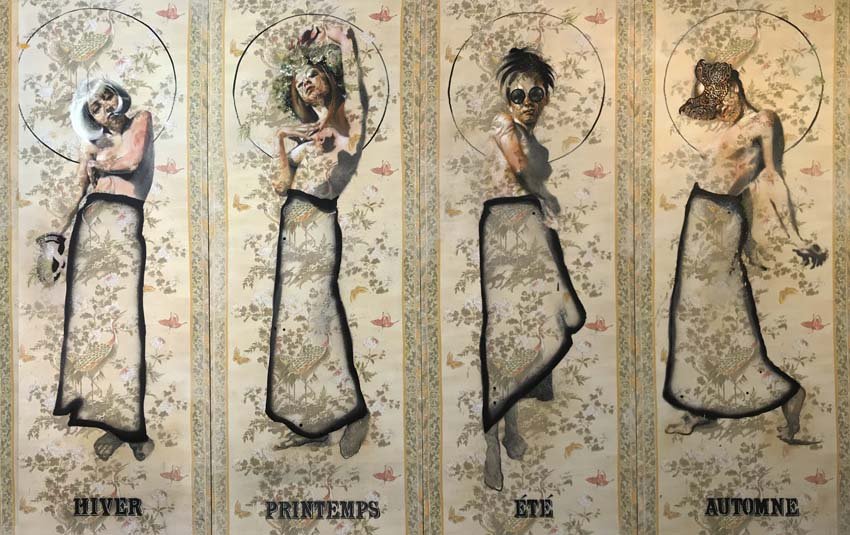

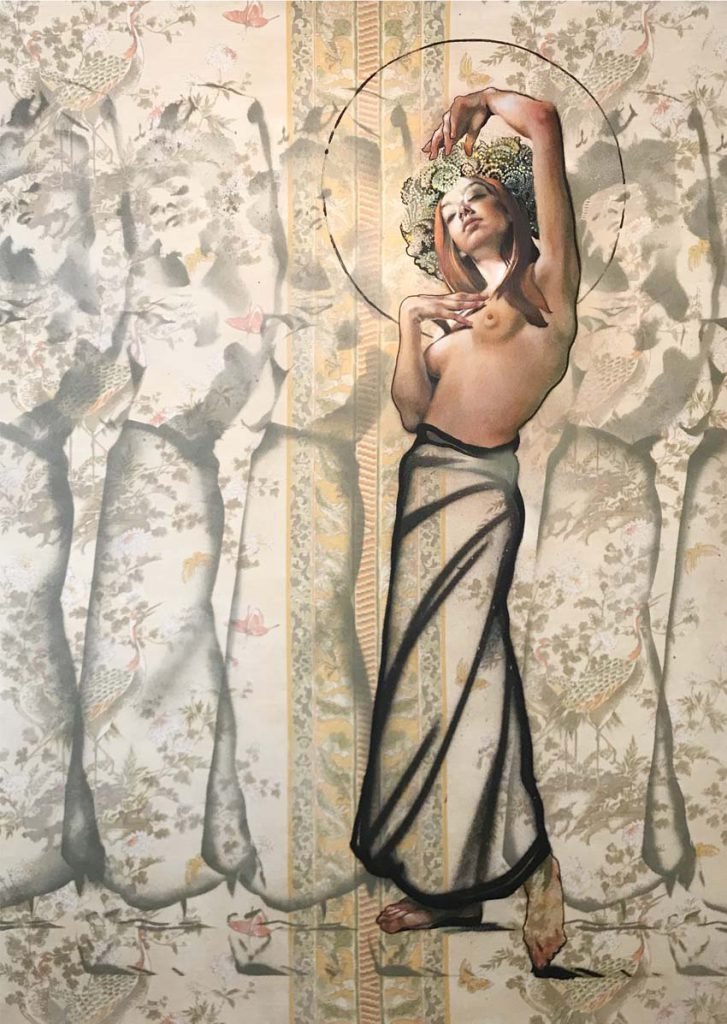

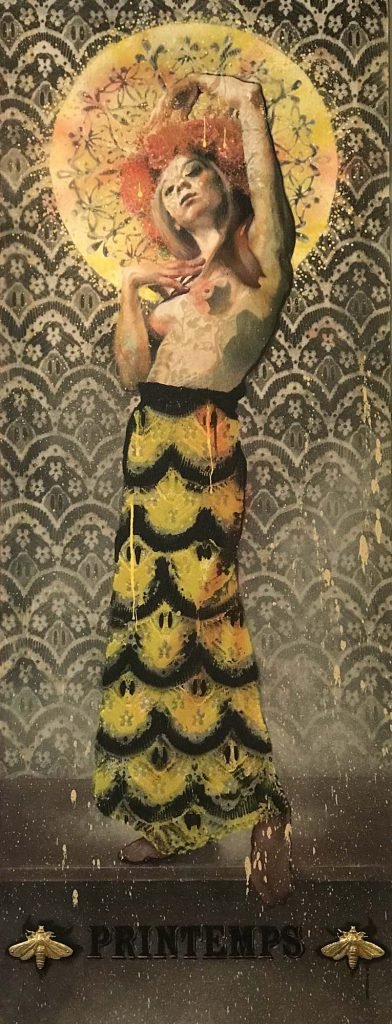

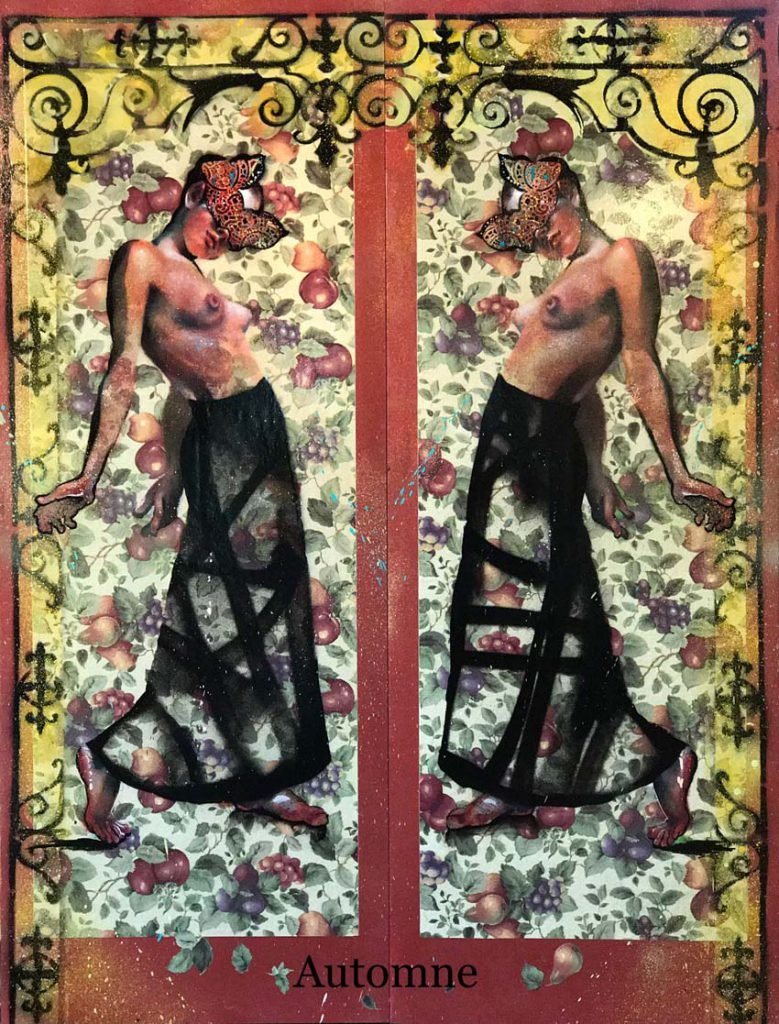

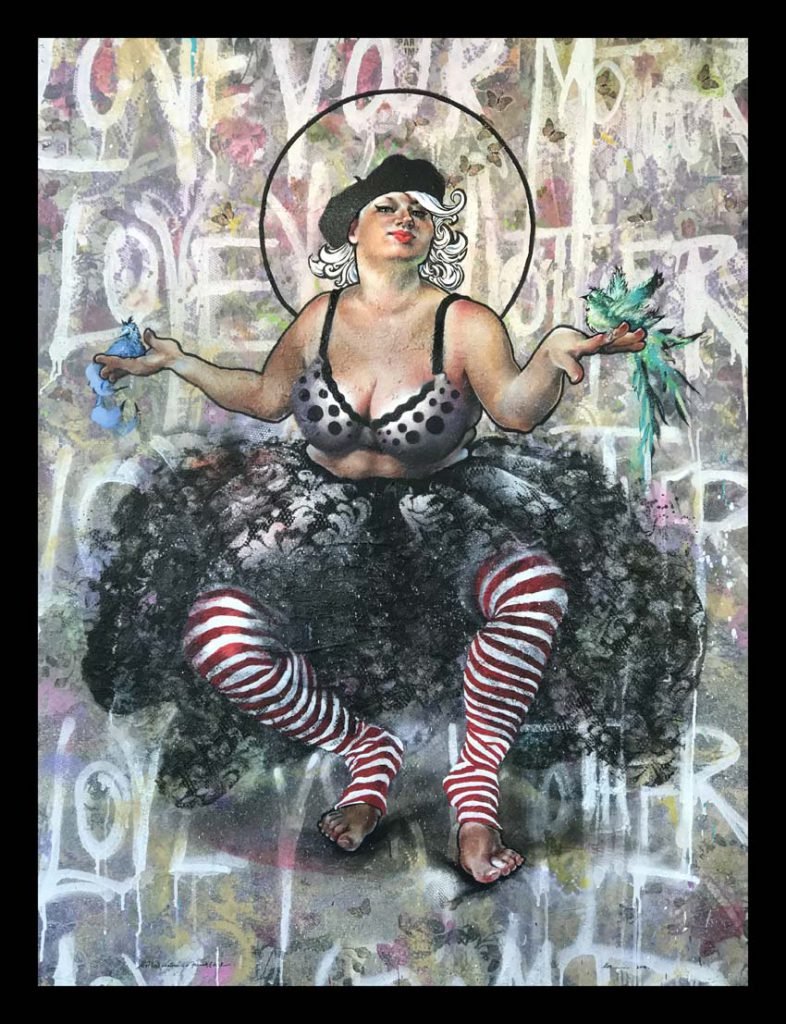

There comes a time in an artist’s life when, having spent so many years exploring a subject, acquiring skills and muscle memory, and creating one’s own unique art history, a new springtime of creativity breaks open the work from the inside. Such seems to be the case with Delaitre’s series “The Four Seasons,” which explodes with patterns, textures, a mix of stylization and naturalism, and with markings that evoke both contemporary graffiti and classical gestures, creating a dual vocabulary all her own. Female figures serve as iconic metaphors for winter, spring, summer, and fall. Among these representations of the seasons, a recurring subject in Delaitre’s work over the last three decades, Mother Nature, has been reborn. In this incarnation, she is a bountifully breasted woman in a beret, a bra, black crinolines, and red and white striped leg warmers, with birds balanced on her fingers. The painting is titled Mother Nature is a French Chick. The master is forever a student. █

Learn more about

Moe Delaitre’s artwork at

www.portraitsbymoe.com/blog.htm