+ By Julia Gibb

What brings a soft-spoken middle school teacher and married father of two out in the wee hours of the night, following a hip-hop icon’s bus to . . . he’s not entirely sure which Washington, DC hotel? The answer, of course, is art. During his childhood, art lifted up Andrew Katz when he needed it and gave him much-needed direction. He now goes to great lengths to complete what are, in essence, collaborative artworks whose finishing touches are the signatures and tags of the hip-hop artists he depicts in his portraits. Katz’s love of hip-hop was born in the mid-1980s when he discovered a mix tape left by his sister in the stereo system after a party, but it took many years before his portraiture and musical obsession intertwined.

Born in Ellicott City, now living on the Eastern Shore, Katz is a proud Maryland resident. When he was in the sixth grade, his father passed away, leaving the family reeling. “Art saved me,” he says, “because I was an average student at best.” He credits a middle school art teacher with recognizing his need for extra encouragement and guidance; with her help, art became a safe haven where he could focus and excel. Building on his skills through high school, Katz started developing his identity as an artist. A teacher for 23 years, Katz offers the support he is so grateful to have received as a teen. He is currently Visual Arts Department Head for K–12 and middle school art instructor at The Key School in Annapolis, teaching drawing, painting, sculpture, and design. “I look for ways to encourage student artists to navigate the creative process through meaningful and thoughtful solutions,” he says.

Born in Ellicott City, now living on the Eastern Shore, Katz is a proud Maryland resident. When he was in the sixth grade, his father passed away, leaving the family reeling. “Art saved me,” he says, “because I was an average student at best.” He credits a middle school art teacher with recognizing his need for extra encouragement and guidance; with her help, art became a safe haven where he could focus and excel. Building on his skills through high school, Katz started developing his identity as an artist. A teacher for 23 years, Katz offers the support he is so grateful to have received as a teen. He is currently Visual Arts Department Head for K–12 and middle school art instructor at The Key School in Annapolis, teaching drawing, painting, sculpture, and design. “I look for ways to encourage student artists to navigate the creative process through meaningful and thoughtful solutions,” he says.

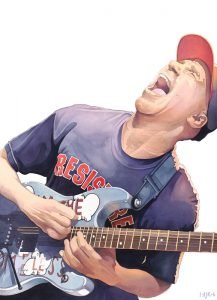

After a semester studying at Towson and later at Catonsville Community College, Katz built up his portfolio and nerve to apply to Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), where he was accepted. Gravitating to tight, realistic renderings, he was confident working in black and white, only to feel he would ruin the drawings when he added color. Artist and MICA professor Phyllis Plattner helped Katz resolve that trepidation, encouraging him to focus on creating a highly developed drawing before starting to add color. He invests 60 to 70 percent of his time and effort in the drawings that underlie his paintings, rendering not only the outlines but also the edges of shadows, colors, and shapes. He then begins experimenting in small areas with paint—in most cases, watercolor. It’s a slow process, he says. “But once I had permission to work in a tight style, I fell in love.” He laughs as he recalls being asked by the Annapolis Watercolor Club to do a demonstration. He warned them, “It’s going to be really boring, watching me work.” He agreed to participate anyway. “Sure enough,” he says, “everyone was checking their watches and yawning. I think I did about an inch-and-a-half section in over an hour and a half.”

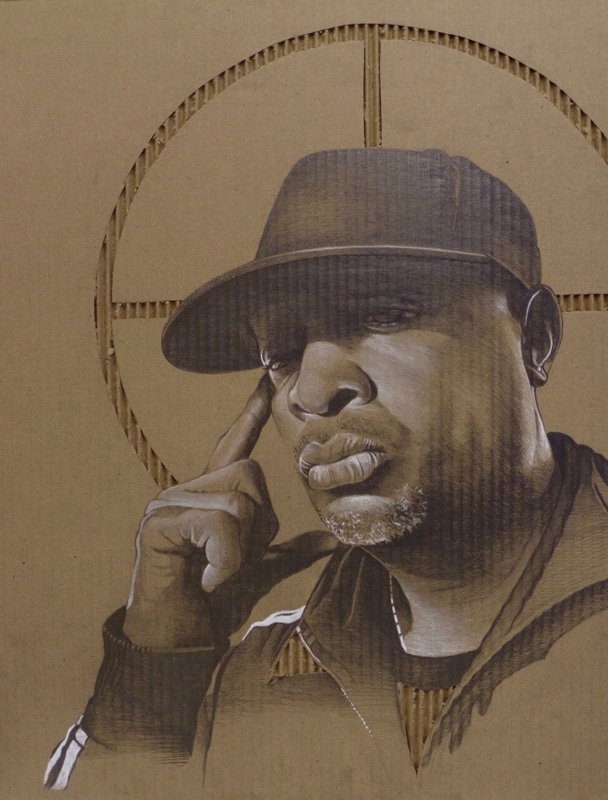

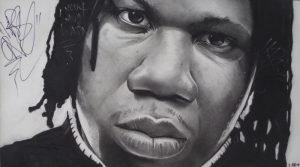

Katz still works in black and white, rendering some of his portraits on cardboard. He enjoys the texture and how the fragility of the drawing surface makes him take his time and pay close attention to the pressure he applies with his drawing tools. “Only one piece has a hole in it,” he smiles, “where the dog jumped on it.” Working first in black charcoal, he allows the cardboard to show through and function as a pigment itself, lending a warmth and depth to the skin tone of the artists he depicts. Finally, he adds highlights in white. Recently he began experimenting with carefully cutting and peeling away the top layer of paper to reveal the corrugation beneath, working the texture into his compositions.

Katz still works in black and white, rendering some of his portraits on cardboard. He enjoys the texture and how the fragility of the drawing surface makes him take his time and pay close attention to the pressure he applies with his drawing tools. “Only one piece has a hole in it,” he smiles, “where the dog jumped on it.” Working first in black charcoal, he allows the cardboard to show through and function as a pigment itself, lending a warmth and depth to the skin tone of the artists he depicts. Finally, he adds highlights in white. Recently he began experimenting with carefully cutting and peeling away the top layer of paper to reveal the corrugation beneath, working the texture into his compositions.

In 2012, Katz added another dimension to his portraiture when he had an opportunity to ask Baseball Hall of Famer Rod Carew to sign a watercolor portrait Katz had made of the athlete. In a humorous nod to the lyrics, “I’ve got mad hits like I was Rod Carew” from the Beastie Boys song, “Sure Shot,” he asked Carew if he would sign his painting, “I’ve got mad hits–Rod Carew.” Carew genially obliged. The piece now seemed finished in a new way, and Katz set his mind on finding the Beastie Boys to add band member Mike D.’s signature to the piece—and succeeded.

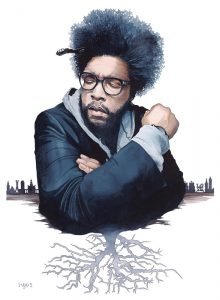

Katz goes to great lengths to procure the tags and signatures of the artists he depicts. He has since gotten the signatures of all the artists he drew who were on that mix tape from the 1980s. “I create these little adventures for myself; I call them missions.” Normally reserved, Katz says, “When I meet the artist, when I get my work signed, it puts me in a place where I feel much more confident to talk to people.” These missions have taken him on many wild pursuits, late nights, and emotional roller coasters. He chronicles them on his blog, THIS MIGHT NOT WORK’ The Art Adventures and Endeavors of Andrew J. Katz (katzart.blog). Typically, his interactions with the artists are positive, the musicians humble and gracious. This was true of Chuck D, who, ultimately gave Katz a job working on the Public Enemy website. “I’ve never met someone so genuinely generous with promotion and empowerment of other people,” says Katz of the artist.

He has also learned drawing on an iPad, illustrating a book while working long-distance with the author and experimented with digitally creating portraits of hip-hop artists. There is something strange to him about these pieces—there is no original, and the sensory experience is lacking. “If I do a watercolor painting, I’ll look down at my hands and I’ll have paint all over my hands, and I’ll smell the paper, and I can erase and see the bits of paper, and I can change the surface.”

He has also learned drawing on an iPad, illustrating a book while working long-distance with the author and experimented with digitally creating portraits of hip-hop artists. There is something strange to him about these pieces—there is no original, and the sensory experience is lacking. “If I do a watercolor painting, I’ll look down at my hands and I’ll have paint all over my hands, and I’ll smell the paper, and I can erase and see the bits of paper, and I can change the surface.”

In 2015, Katz met artist Cory L. Stowers at a hip-hop show in DC. Stowers, knowing of Katz’s interest in augmented reality apps, invited him to be part of one of his projects. Katz did conceptual renderings for a piece centering around African American activist Paul Robeson, including a timeline of Robeson’s life and achievements. He also participated in painting the mural itself. “It was strange,” he says, “the street artists were trying to capture my style on a very irregular wall.” The finished mural is a “living timeline” of Paul Robeson’s life, including “history pods”—six-foot circles with line segments in between, creating a visual timeline. Viewers could scan a pod with their devices, and a video with related content would appear.

He continues to expand his DC connections. In May 2018, Katz had a solo show of his portraits at Blind Whino, an arts and culture collective based in southwest Washington, DC.

Knowing that technology plays a major role in his young students’ lives, Katz strives to keep up with software and apps that can enhance and extend the art viewing experience. For one project, his students dressed up in Civil War costumes. “We made them look like tintypes,” he explains. When a viewer scanned the images with a device, a video popped up, featuring students reading Civil-War-style letters from home. “We put candles on, had all these props from the Civil War era . . . it’s really sophisticated.” He emphasizes to his students that video and apps aren’t a substitute for the hands-on part, only an extension. “We have to model our behavior, walk the walk, make sure the kids see us doing it.” He’s honest about what he doesn’t know as well. “That’s how they learn,” says Katz, “not just by me talking.” █