+ By Geoffrey Young + Photos by Alison Harbaugh

The novelist Lucia St. Clair Robson’s latest release, Devilish (2014), is a thriller about murder, romance, environmentalism, supernatural visitations, and the friendship between four formidable women. It takes place in Cliffs of the Severn, Arnold, which is also where Robson’s life in Pines on the Severn takes place. Sitting in her living room, she indicates through the picture window the homes of her characters’ real-life counterparts: “Faye lives there. I can throw a rock and hit it. Doc’s house is on the playground at the corner . . . This is Alice’s house.”

The importance of place is a constant in Robson’s work, though Devilish is a departure from the historical novels for which she is mostly known. Heretofore, she has transported readers to nineteenth century Texas, Tennessee, and Florida, to eighteenth century Japan, even to colonial Maryland. Given her life experience, itinerancy of time and locale is no surprise. Born in Baltimore and raised in Southern Florida, Robson lived in Venezuela during a stint in the Peace Corps, Japan (“Just for the hell of it,” she says), Arizona, and South Carolina, before settling back in Maryland.

Robson got her start as a novelist on a lark, after meeting her future husband, the science fiction writer Brian Daley, at a writers convention in Baltimore in 1979. A librarian at the time, she happened to mention her interest in the life of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was kidnapped in 1836, at age nine, by Comanche Indians, and later married into their tribe. “Rescued” by Texas rangers 24 years later, Parker spent the rest of her days trying to return to her Comanche family. Daley’s editor, Owen Lock, suggested that Robson write a novel about Parker and send him a sample. “I told him not to be ridiculous,” she says, “I didn’t know how to write a book.” But she got started and eventually sent Lock six chapters. He called her with a wry acknowledgment: “I got your piece of trash,” he said, and subsequently forwarded the manuscript to an editor at Ballantine, who offered Robson a substantial advance on what would become Ride the Wind.

It all seemed to happen by chance. “I didn’t dream of becoming a novelist,” she says. Today, she boasts two Spur Awards and a Lifetime Achievement award from Western Writers of America.

The success of Ride the Wind, in 1982, set off a string of works involving American Indians, including Walk in My Soul (1985), about Tiana Rogers of the Cherokee, and Light a Distant Fire (1988), depicting the heroism of the Seminole tribe of Florida in the 1830s, a people that had fascinated her since learning about them in the fourth grade. “They held out against overwhelming odds,” she says. “They never surrendered. They never signed a peace treaty.”

Adversity is a common theme in Robson’s work. “Most of my books are about underdogs. I guess that’s why I write about women so much. In history, women are told to shut up and don’t bother people.” Robson feels that plumbing the lives of historical underdogs offers a salutary benefit to reader and writer alike. She says that such stories provide perspective. “When you know how bad it was, it helps you get through day to day.”

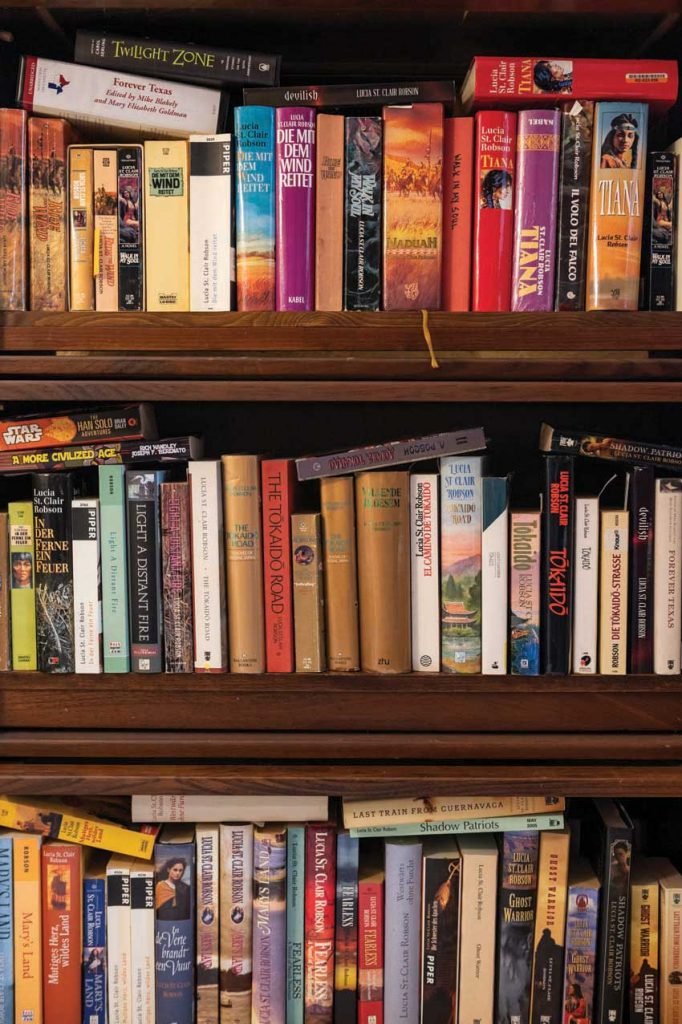

But there is another sort of perspective at play in Robson’s work, something akin to possession or channeling, is necessary to successfully weaving fiction into the lives of real people. “In order to write about [historical figures], you really have to get into the time, the place, and hopefully their heads.” Her process begins with copious research — “I’ve run out of shelf space,” she says — and diligent organization. An old library card catalog, located in her wood-paneled home office, is stuffed with cards indexing the source of every fact contained in her novels. From this hard-earned perch of historical mastery, Robson’s imagination takes flight.

Perspective, then, becomes more than clarity gained by comparison. It represents experience by proxy, occurring in the mind, and it effects an almost magical transportation. “When you’re writing about [an event], you’re no longer a spectator. You’re a participator. These people become your friends.”

So, too, do their descendants. Robson’s empathetic portrayals of the life of native peoples led to her formal adoption into two tribes, which meant taking on tribal names. To the Comanches, she is Dek Wa Wop, or “one who speaks for others.” To the Cherokees, she is White Hawk.

Such acceptance has been primary for Robson. “[After Ride the Wind came out], I wasn’t worried about what the [literary]critics would say. I was worried about what the Comanches would say.”

In the case of the Cherokee descendants of Tiana Rogers, the family was impressed by more than just the literary merits of Walk in my Soul. “I got a phone call from someone called Little Dove after the book came out. She said, ‘The family wants to know where you got those stories.’ I said, ‘Well, I either read them or I made them up.’ She said, ‘No, those are stories only the family knows.’” Little Dove went on to describe the family patriarch, known as Uncle, who kept by his bedside a Bible and a thoroughly marked-up copy of Walk in my Soul. When Little Dove told Uncle the elders wanted to adopt Robson, he replied, “You can if you want, but she’s been with the family a long time.”

Robson folds her long frame into a low living room chair, reflecting upon her stories. “I’m not spooky. I’m not religious. But there are unexplained things that happen. Some connections get made.”

A particular connection came in 1996, not long after her husband, Brian, had succumbed to pancreatic cancer. A close friend called to tell her Brian’s spirit had visited him, “big as life.” Soon thereafter, Robson was involved in a car accident on Route 50. Once home, “I was kind of shaken. I was lying on the couch. And I just felt this overwhelming sense of love . . . It was the most intense thing I’ve ever felt. And I guess it was Brian.”

She looks out the window from her low chair, pensive, amused. “A lot of these houses have ghost stories.”

Robson calls Devilish her most autobiographical novel. She began it soon after Brian’s passing, but set it aside. “It was too whiny, too self-pitying.” Molded by time’s softening hand, the novel is fun, inventive, strange, and rich with intricate detail. Supernatural visitations mostly take the form of incubi—raunchy sex demons—but the women of the novel hold their lost loves vividly in mind, as Robson does hers, and feel their presence, big as life.

Devilish may represent a departure for Robson the historical novelist, but it continues a creative process emphasizing experience borne of imaginative flights and an orientation toward unseen worlds, whether they be epochs long past or strange occurrences right next door. Up next, Robson aims to cinch two strands of her interest: she’s working on a novel about Jefferson Davis’ Camel Corps experiment in the pre-Civil War southwest.

“Maybe a haunted guest house kind of thing,” she hints, a sparkle in her eye. █

For more information, visit

www.luciastclairrobson.com.