+ By Dylan Roche + Photos by Alison Harbaugh

Even though it’s been 15 years, Scott Newcomb still remembers a particular day. During the heat of summer in New York City, where he and his wife were living at the time, he was out, selling his art in Union Square. It had been seven weeks since he’d sold anything, and he was feeling discouraged. “In the summer, it’s hard as hell to sell artwork because it’s so hot,” he says. “All the art people tend to be out in the Hamptons or on the water. If I were to give advice to anyone trying to sell their artwork in New York in the summer, it would be to take a vacation.”

It was a good thing that Newcomb was not on vacation that day. A couple approached him and took a fervent interest in his multimedia abstract pieces, and one in particular caught their eye. English wasn’t their first language, but Newcomb understood that they wanted to buy his art as a gift. “Our friend is a big art collector,” he recalls they said. “He needs to see this. He will love this.”

A couple of months later, Newcomb got a call from a man in Zurich, Switzerland, who told him he had acquired that piece and asked if it could be part of a tour. “I was blown away that somebody got my artwork and wanted to include it in a tour,” Newcomb reflects. “It was going to be shown in two different museums of contemporary art.” Thus Newcomb came to have his work exhibited internationally. The piece continues to have a home in Europe as part of the Annette and Peter Nobel Collection at the Museum of Modern Art in Salzburg, Austria. His work is also displayed in Japan and England.

After 15 years, that moment stands out as significant in Newcomb’s career. “Is there ever a big break?” he muses. “I’ve had those moments of affirmation that keep me going, and maybe those are big breaks.”

Newcomb has always been surrounded by artistry and creativity. He grew up in a family of artists, thinking of the title of “Artist” as something to be revered, with positive energy. He went on to study briefly at Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore before he and his wife, Mary, whom he describes as his greatest influence, moved to New York City. Today, the couple share studio space in their Annapolis home. Although they “feed off new places and new experiences,” they think of Annapolis as their home base, their “special, safe island.”

Newcomb has also nurtured a love of teaching, something he discovered while working at The Crucible, a multidisciplinary arts center, when he lived in California. He realized that teaching would always be a part of what he does to some degree, and he brought that passion with him back to Annapolis, where he teaches 3-D and slime (yes, slime) classes and seminars at ArtFarm.

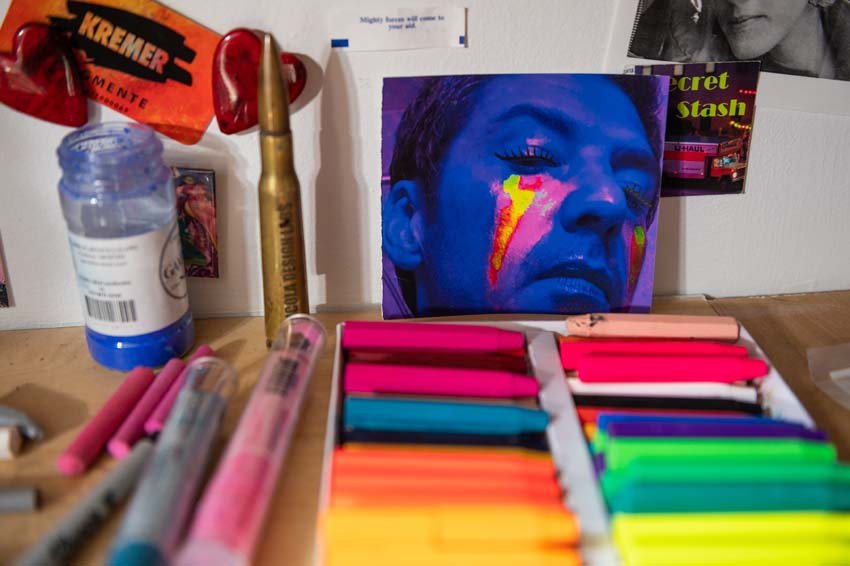

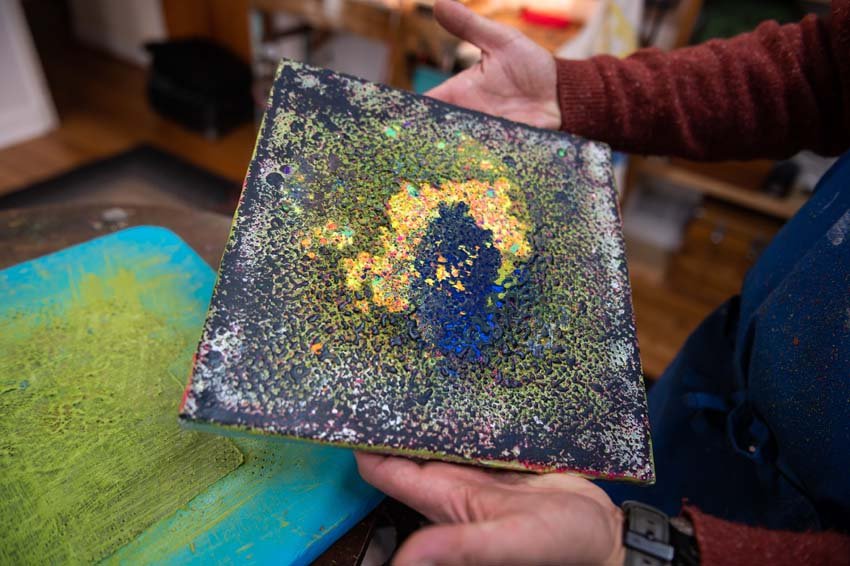

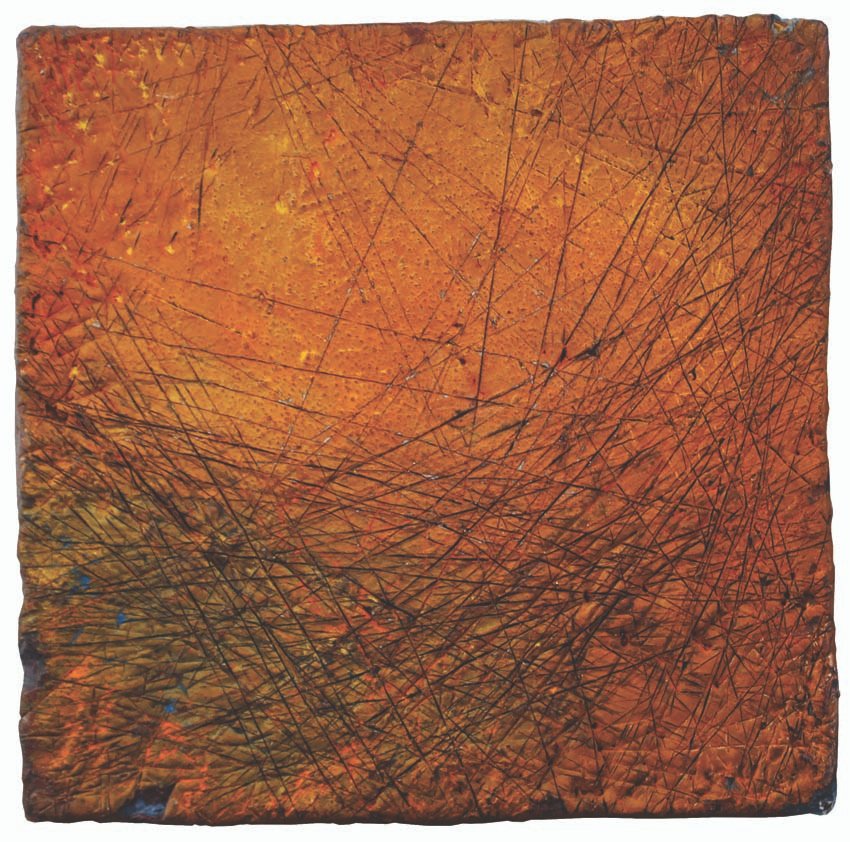

All these many places and experiences that Newcomb enjoys have shaped his unique method of making art over the years. In his youth, he mastered the use of watercolors, acrylics, and oil paint. In college, he moved on to glassblowing and metalworking. Today, he works with found objects, wax, and pigments to create his colorful abstract pieces.

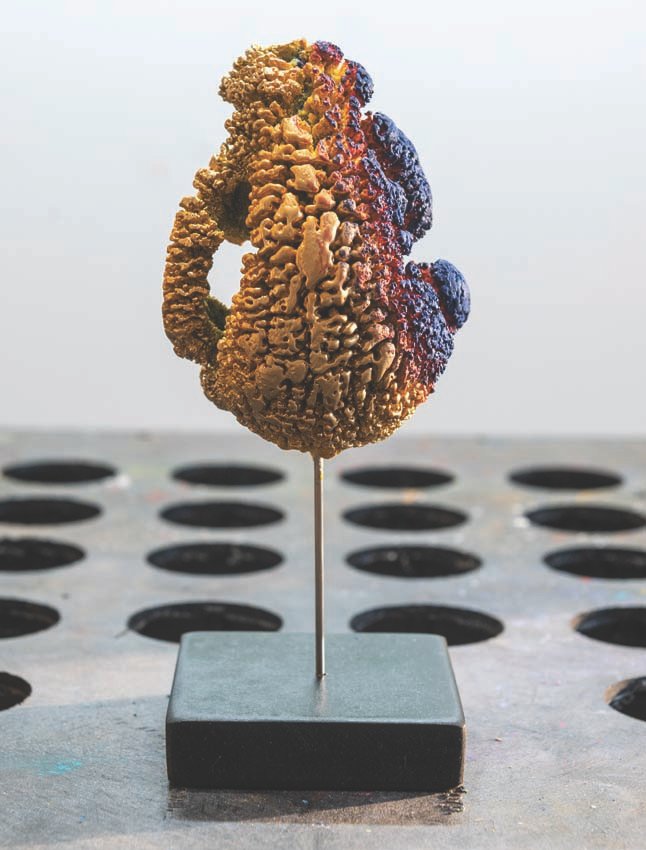

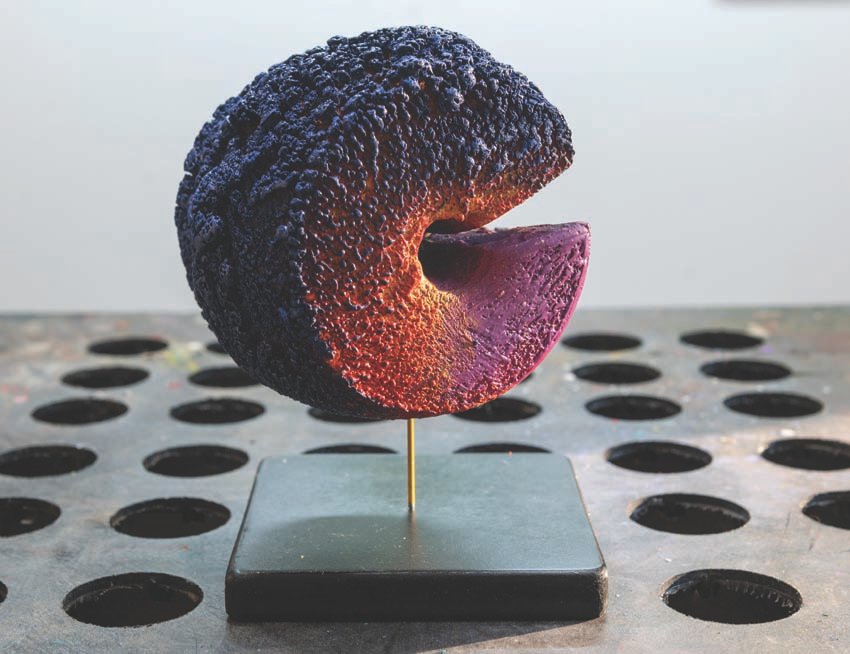

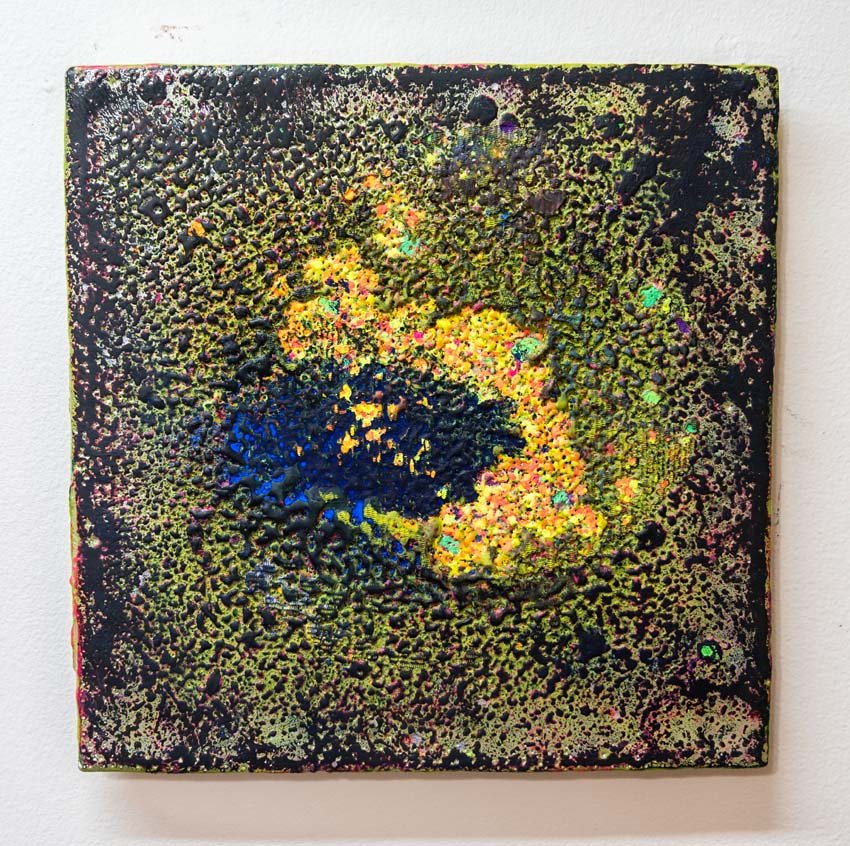

Sometimes he works with panels, which absorb the wax that he melts under a torch. Once the panel is saturated with wax, he can heat it up, cut into it, glaze it, and color it with pigments. He uses everything from screws and other hardware to broken pieces of textured plexiglass to achieve the look he wants. Other times, he creates what he calls pops, mixed-media sculpture that can be held on a stick and admired from all angles. “Pops are less restrictive. They can move around. People can pick them up and look at them,” he explains.

Whenever he finds an interesting object, whether it’s a boat buoy salvaged from a beach or an animal skull found in the woods, his imagination goes to work, transforming it into a beautiful work of art or, as he sometimes describes his process, “praying something into existence.” This process that he’s developed over the years requires him to take his time with each step, something that’s difficult when he’s so eager to see the finished product. “So many other elements of my life give me instant gratification—my phone, my computer, you know,” he says. “Not getting it can be really hard. But it’s good. It’s healthy. Having the patience to ride it through and not rush it can be hard.”

Patience pays off, though, as his art seems to always elicit a reaction from everyone. When he was selling art in Union Square, he would hear raw, guttural expressions of admiration in equal measure with more eloquent responses. He recalls one interaction he had with a man who exclaimed in a New Jersey accent, “That’s beautiful, man! That’s beautiful!” (This particular fan even tried to buy one of Newcomb’s pieces for $400 more than what somebody else had already paid for it—high praise indeed.)

This kind of interaction really drives Newcomb as an artist, as he considers making friends to be a superpower that he possesses. He has an outlet for connecting with and supporting other artists via the Maryland Federation of Art, through which he recently participated in events such as the art walk and the Art of Paper show, both held in February 2022.

These social outlets are important because, for him, it’s easy to get lost in his art. “It’s tough to balance being an artist and a partner and a father and keeping everything cool, keeping everything equal,” he says. “In my art space, I can get lost for days, just living off green tea and music, just . . . working. But I have to be a part of feeding and cleaning, and I want to be really participatory because I know that really informs my artwork.” █

For more information, visit scottnewcombart.com.