+ By Desiree Smith-Daughety

Friends of Mitzi Bernard raise nary an eyebrow when invited over to help cut out naked women. Over glasses of wine and old issues of Playboy magazine, they form a modern-day women’s circle. In the age of #MeToo and the upcoming hundredth anniversary of US women’s right to vote, Bernard finds that the conversation over how women are viewed isn’t yet over.

“I’m a product of the seventies and equal rights—it comes out in my art,” says Bernard. “I take a picture that society might perceive or judge in one way and incorporate it into another piece of art to tell the story of strength, power, and lovability. My idea is to find beauty and strength in places we may have ‘judged’ differently, whether it be my different kind of art, or our judgments of others, particularly women.”

Currently a chief of staff for a legislator in Maryland state government, Bernard recently took a year off to develop her art and discover her artistic voice. Previously, she served for 27 years as executive director for Bay Community Support Services, a nonprofit that she started. Bernard has always taken art classes, and initially she worked in paint, but fresh inspiration came seven years ago, when she saw Annapolis artist Jeff Huntington’s work. “Up close, it looks like little pieces of paper, then you stand back and see the whole image,” she says. “I was so astounded, I had to figure it out.”

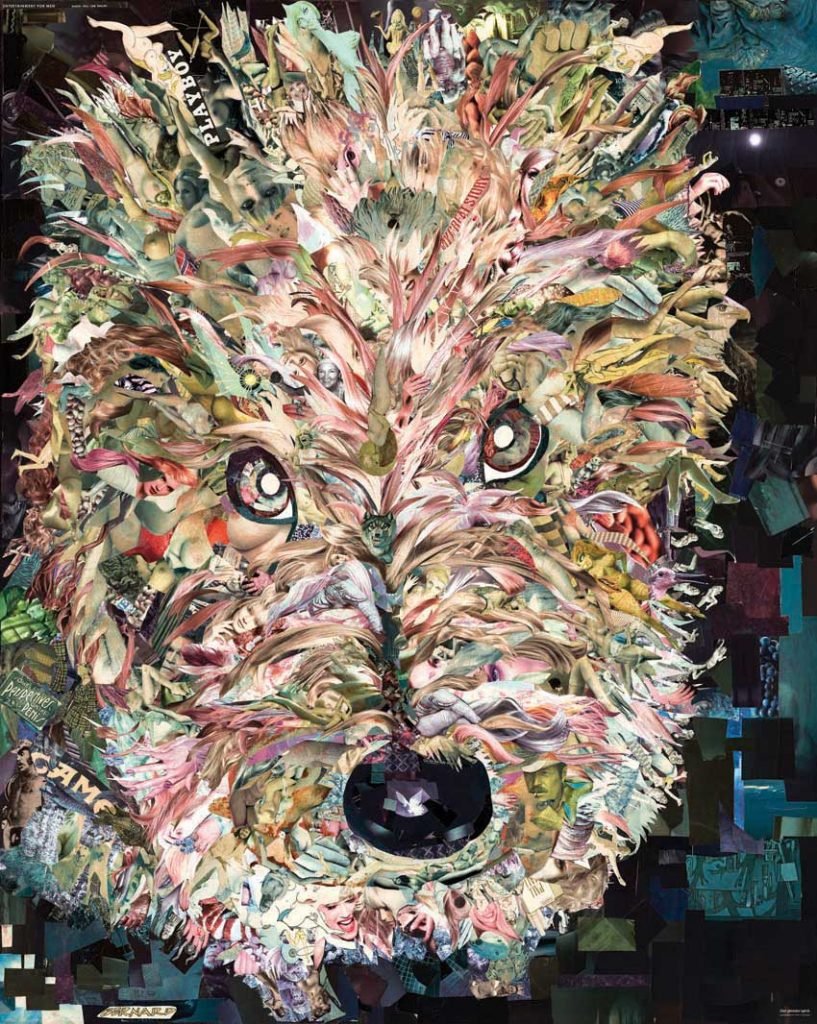

Her first piece using collage as the medium was completed five years ago. Stanley, one of her three rescue dogs (Henry and Louie complete the trio), served as the model. She wasn’t sure how to depict his flowy hair, and the piece stalled. Her daughter, Zoë Nardo, came across some 1970s Playboy magazines in a vintage store and got them for her to possibly use. Bernard scissored out pictures of women and advertisements, and the piece came together.

The finished work, Playboy Stanley is mesmerizing. Viewed from several feet away, the colors work together to give a paint-like appearance. Draw closer, and one can discern the individual paper strips. The eye roves across patterns, searching out image details that could be lurid when only a single woman is seen, vulnerable in her nakedness, but when grouped together, in the context of the piece, offer a more collegiate portrayal of sisterhood. “It shows how we can find innocent lovability and beauty in places we might not have considered,” says Bernard.

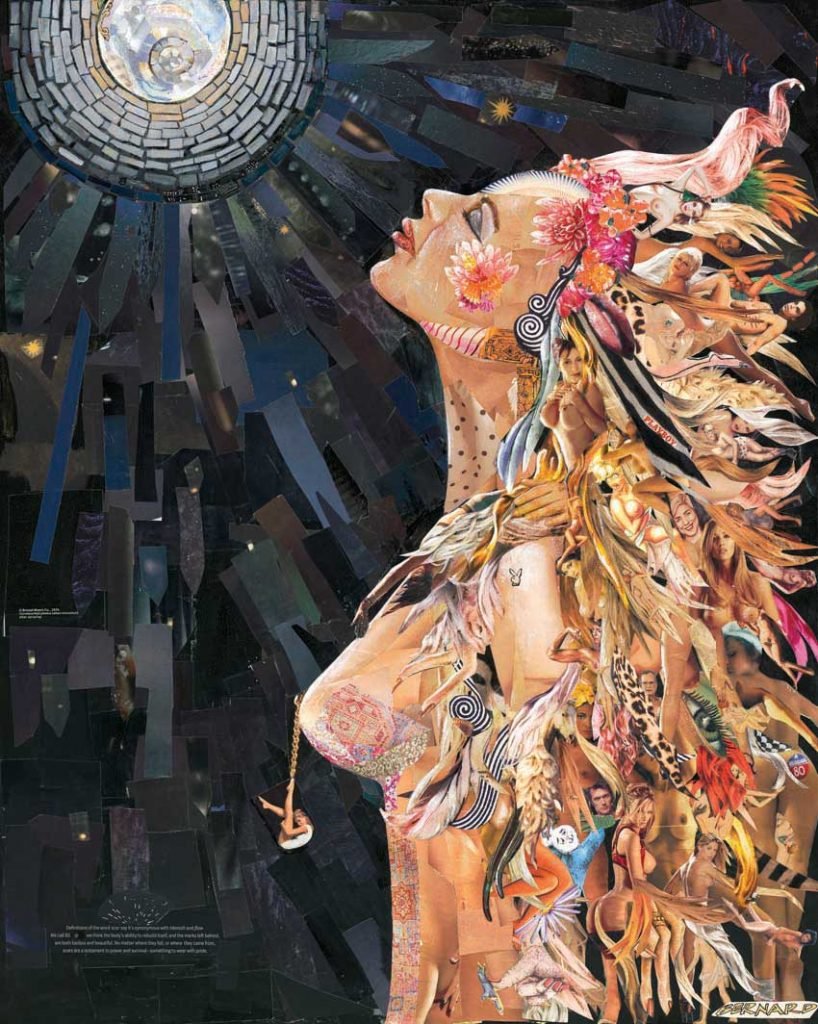

During her work hiatus, she created additional pieces, using papers cut primarily from old Playboy magazines, which are now provided to her by friends and friends of friends, along with other types of paper and a bit of paint. ScarFace, made primarily of 1980s—and some 1970s-era images, represents the pain that women experience from scarring throughout their lives that makes them stronger. The female figure’s stance exudes power, with eyes closed and face content, tilted up toward the sun. Suspended from one nipple is a picture of a woman in a coquettish pose, presenting a humorous reclamation of her power outside the pages of Playboy.

Bernard takes inspiration from beloved connections around her, including her daughter and the family’s animals. Female Fury is based on Rachel, one of her two horses, and portrays an angry mare, its painted eye piercing in its wisdom, defiance, and ferocity. With Female Fury, Bernard says she’s conveying that women aren’t meek but have strength; they’re angry, have a long way to go, and are going to be vocal about it.

Female Fury was acquired by Farah Farhoumand, a dentist in Washington, DC, who learned of the piece through Bernard’s husband while on a boat-buying search around Annapolis. He had told her that his wife was an artist and showed her a phone photo of Female Fury. The piece resonated with her, recalling a particularly difficult time, when she and her sister-in-law had to stand strong while working to bring justice for a child in their family who had been victimized by a relative. “It was such a powerful image for me,” says Farhoumand. “Sometimes art or a song will just hit your soul. I was moved because it was about the beauty and strength of women. We all have it, no matter what shape, color, background, country, or race.”

Miss Conception has a central message about how people make value judgments that aren’t always accurate and can dismiss the notion that we’re made up of different attributes. At the bottom center of the piece is her daughter’s image. An array of Playboy images fan above her head, images that represent judgements that may befall her, and she’s bookended by watchful, judgmental eyes. Wings sprout from her back, the feathers displaying words describing the good things she has done. “We are all made of good and bad,” says Bernard. “There’s a Shakespeare quote tattooed on her fingers that says, ‘there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.’”

Each of Bernard’s works takes about 200 hours to create. She starts with a message and an image, but the last five hours in the process bring forth the result, as she selects from her baskets brimming with cutout pictures. When determining a specific picture’s inclusion within a piece, she considers multiple variables, such as color, size, movement, and hue. “I look at each piece of paper placed up close and then step back to see how it looks in the piece as a whole,” she explains. “Sometimes one little piece of paper can change the entire look of the work or surprise me and take the piece in an entirely new, fun, or terrible direction.” She will have a basic plan when she starts out, but the piece usually takes on a life of its own, evolving as she proceeds.

For her first solo show, which took place in February 2020 at Tsunami in Annapolis, Bernard created two new pieces. At the time of this writing, one was still in progress, set up on her workspace. It was being designed to be smaller than her prior works, with an intended message of coming awake—she had roughed in a butterfly with a woman’s face emerging at the head. She feels that Tsunami is a perfect venue for her work. Bernard says, “The art I create isn’t considered fine art, it’s considered outsider art and is appreciated more by people with an open mind who are open to my message.”

Bernard considers herself an outsider, closet artist, which she describes as being akin to a closet smoker—someone who’s not really such, with a nod to the closet in which the women in the cutout images have been harbored. Notwithstanding, her work is gaining wider exposure with its inclusion in group shows such as SoCo Arts Lab, and it’s resonating with viewers.

Recently, a woman in charge of the annual Playboy reunion contacted Bernard. She’d found her work on social media and was inquiring about using Bernard’s images at an upcoming Playboy event. “I was excited she loved them and felt the message was a positive one,” says Bernard, “and to know that my message of strength and power in women was being heard by the women who were making those statements in my art.” █

For more information, visit

www.mitzibernardclosetart.com.