+ By Leigh Glenn

The real gem . . . is Jim Hollan’s Dove . . . Just beer and soda pop, but they really pack them in. There are chess tables in the corner for devotees, and the customers provide their own entertainment with guitars, banjoes, flutes, fiddles—you name it.

–Dick Haefner, from a 1976 Annapolis & Trust Co. guidebook to Annapolis

Today, Jim Hollan lives on an inlet off the Magothy River, where he kayaks with the grandkids and paints. But when he was just 28, he launched The Dove in the basement of 33 West Street, where Rams Head Tavern operates today. Hollan, a first-generation Irishman, was born in New York and grew up in Spanish Harlem before moving to Washington, DC, for college and graduate school.

Owner of The Dove in the mid ’ 70s, Jim Hollan, among the debris after a fire damaged the cafe. Photo courtesy of Jim Hollan.

He became acquainted with Annapolis through a professor, whose septic system in St. Margaret’s he helped build. It was 1962, and they would come into town for supplies. “I was waiting for Jimmy Stewart to run down the street,” says Hollan, of the vibe. “People would stop and say, ‘Hello! Are you visiting?’”

In 1968, he moved to 239 Prince George Street and taught at The Key School. He played guitar, autoharp, and mandolin in Jumpers Hole String Band with guitarist Neil Harpe, who taught him blues.

Hollan got to know many business owners who had lived there in the 1940s and ’50s. They told him how people came to Annapolis on Saturdays to shop before going to supper. The shops closed around 6 p.m. and reopened around 7:30 p.m., when people returned to purchase what they needed.

But drastic, vibrancy-dimming change had come to Annapolis in the 1960s. Downtown businesses suffered after the creation of Parole Plaza, with all its parking. Urban renewal efforts decimated the area around Northwest, Washington, Clay, Calvert, and West Streets, a neighborhood of primarily African-American residents who had been economically prosperous and wealthy in its sense of community. The local Safeway, at Calvert and West, was swept away, leaving garages and parking lots.

“At five o’clock, it would take you an hour and a half to walk around City Dock, because every other person was someone you knew,” says Hollan of the days before Parole was developed. But by the late ’60s, he says, “You could roll a bowling ball down Main Street after six at night and hit nothing.”

To earn extra money, Hollan played guitar at Middleton Tavern, taking requests from patrons. He admits that he was not a seasoned musician or performer, but because he made more in tips than teaching, he left The Key School to perform.

Hollan also felt that, while Annapolis had an artistic side, it lacked an arts place. Art was done “in living rooms,” out of the public eye. He wanted a place where people could meet—to make music, play chess, read poems, paint, or draw. He saw potential in a site on West Street.

At the time, 33 West Street was an old, run-down building owned by Charlie Marsteller, whose vision, says Hollan, was to have craftspeople downstairs—in a space Marsteller called The Ark—and to rent rooms upstairs. Back then, Reverend Joe Holland, an Annapolis native who lost a leg in World War II, ran a shoe shine parlor in the building’s basement after being displaced when the Safeway was torn down. Lawyers and judges dropped off their shoes on the way to the courthouse. Holland agreed to move his shoe shine space upstairs, except he needed to be there when people dropped their shoes off. “I said they can drop their shoes at the bar,” says Hollan.

At the time, 33 West Street was an old, run-down building owned by Charlie Marsteller, whose vision, says Hollan, was to have craftspeople downstairs—in a space Marsteller called The Ark—and to rent rooms upstairs. Back then, Reverend Joe Holland, an Annapolis native who lost a leg in World War II, ran a shoe shine parlor in the building’s basement after being displaced when the Safeway was torn down. Lawyers and judges dropped off their shoes on the way to the courthouse. Holland agreed to move his shoe shine space upstairs, except he needed to be there when people dropped their shoes off. “I said they can drop their shoes at the bar,” says Hollan.

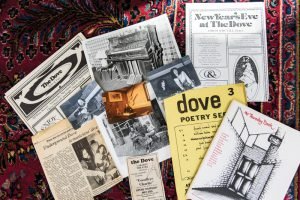

With that agreement in place, along with the lease—Marsteller insisted it be named The Dove, a counterpart to The Ark, after the two ships that landed in what would become Maryland—Hollan bought school desks from the St. Vincent de Paul Society in Baltimore and pews from a local church, set up some chess sets, arrayed stringed instruments along the walls and a pump organ near the single window up front, got a second-hand cooler from distributor Sam Katcef and developed an unheard-of menu of 30 to 40 bottled beers, and opened for business.

It was 1973, and The Dove took off.

The place drew all kinds of people, including legislators, jazz pianists Monty Alexander and Earl “Fatha” Hines (who played on the pump organ), multi-instrumental musician Dick Seabrook, and Sam Katcef’s son, flautist Neal Katcef. Those who gathered could hear anything from soft rock and country to folk and choral music. One night, the place was packed, people were playing old-time Appalachian music, and some members of the National Symphony Orchestra came with their instruments and joined in. “Boat people,” those who moved boats up and down the East Coast, often visited. The late Don Cook, an esteemed visual artist, would stop by to sketch. Thursday nights were for the poets, and, in time, The Dove published a collection of their poems called The Thursday Book. Anyone, poet or musician, shy or outgoing, could try out their music or their lines on those in attendance and, in that way, create community.

By 1976, Hollan leased a larger space for The Dove at 26 West Street, which previously housed the Royal Restaurant, run by Savvas Pantelides, grandfather of Annapolis Mayor Mike Pantelides. Friends pitched in and revamped the space. The Dove carried on until the next year, when a fire destroyed it.

The Dove at 33 West Street was like a dandelion forcing its way up through the cracks of a town undergoing big changes. Many of its seeds have spread far and wide, through music, poetry, and visual arts. Some seeds landed nearby, such as guitar maker Paul Reed Smith, who lived upstairs and whose band, Jude, sometimes played at The Dove. Other seeds have lain dormant and are now beginning to sprout—something that gladdens Hollan. “It feels like time repeating itself on West Street,” he says, “and I tip my hat to this great group of people out there doing it.” █